THE ELECTRIC CHAIR’S FIRST WOMAN: How Martha Place’s Descent Into Madness Ended in Infamy

On March 20, 1899, history was made at Sing Sing Prison in New York, but not for reasons anyone would celebrate. Martha Place, a 49-year-old Brooklyn housekeeper turned murderer, became the first woman to die by electric chair, a punishment reserved for her brutal killing of her 17-year-old stepdaughter, Ida. The crime, driven by jealousy and rage, involved acid and smothering, shocking the public and cementing Place’s infamy as the “Brooklyn Murderess.” Her execution, fraught with logistical challenges due to her gender, sparked sensational headlines and continues to captivate audiences, with social media users sharing haunting mugshots and newspaper clippings. This story of Martha Place’s troubled life, heinous crime, and historic execution offers a chilling glimpse into the dark corners of human emotion and the evolution of capital punishment in America. Let’s dive into the details that made this case a landmark in history.

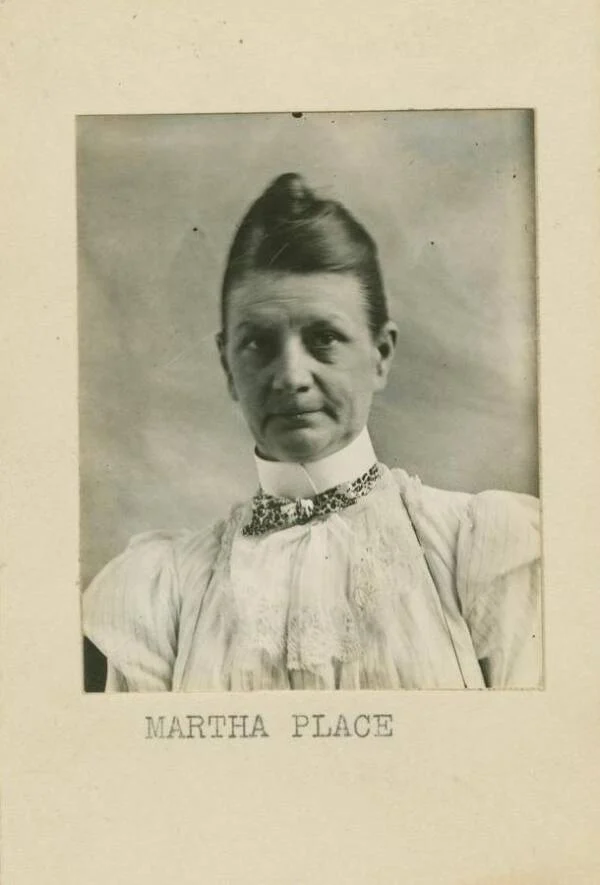

A mugshot of Martha Place taken at Sing Sing Prison. 1899.

The Troubled Life of Martha Place

Born Martha (Mattie) Garrettson on September 18, 1849, in Millstone, New Jersey, Place’s life was marked by hardship from an early age. At 23, a devastating accident—a moving sleigh struck her head—left her with lingering injuries, as her brother later claimed she “never fully recovered,” per the Trentonian. This trauma may have shaped her later struggles, which included a failed marriage and the loss of her only son to adoption after her husband abandoned her and died. By the time she found work as a housekeeper in Brooklyn, Martha’s life was a series of misfortunes that set the stage for her descent into violence.

The press later wrote that jealousy drove Martha Place to kill her stepdaughter.

In Brooklyn, Martha worked for William Place, a widower with a young daughter, Ida. Their marriage made Martha Ida’s stepmother, but instead of familial harmony, tensions brewed. The New York Times reported during her 1898 trial that Martha’s jealousy of Ida, whom she believed her husband favored, “rapidly changed into hatred for the little girl.” As Ida blossomed into a “pretty young woman,” Martha’s resentment grew, fueled by her own insecurities and the contrast between them. This simmering envy, as @HistoryVibes tweeted, “turned a housekeeper into a murderer—jealousy was Martha Place’s undoing.” Her story reflects a tragic spiral, where personal pain and perceived slights culminated in an unthinkable act.

The Gruesome Murder of Ida Place

Martha Place killed her 17-year-old stepdaughter Ida Place in 1898.

On February 7, 1898, a heated argument at the Place household in Brooklyn escalated into horror. According to Amazing True Stories Of Female Executions by Geoffrey Abbot, Martha and William clashed, with Ida siding with her father. After William left for work, Martha confronted her stepdaughter. She later told police, per the New York Times, “His daughter sided with him as she usually did and slammed in my face the door of her room when I went to speak with her. That made me feel mad, so I got some acid from my husband’s desk and threw it into her face.” The attack was vicious—Martha splashed acid into Ida’s face, causing excruciating pain. An autopsy suggested she didn’t stop there, likely smothering Ida by “heaping” bedding on her as she writhed.

Martha’s violence didn’t end with Ida. Anticipating her husband’s return, she armed herself with an axe from the cellar, claiming, “I was afraid he was going to attack me.” When William arrived, she struck him, leaving him bloodied and stumbling into the street for help. Martha then fled to the kitchen, attempting suicide by turning on the gas, but police arrested her before she could succeed. The brutality of the crime, as @CrimeHistory posted, “shocked Brooklyn—acid, smothering, and an axe attack in one day? Martha Place was a nightmare.” The public’s horror fueled intense media coverage, setting the stage for a sensational trial.

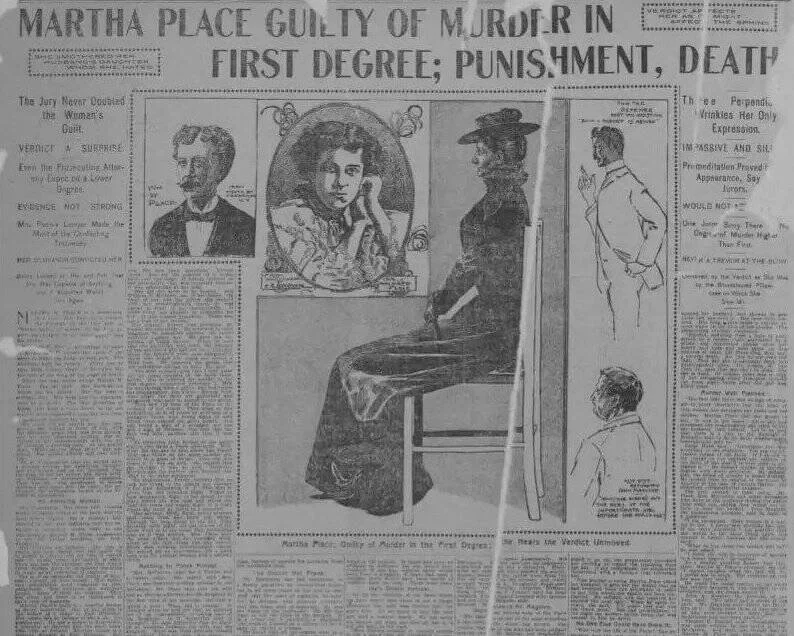

Newspaper coverage of Martha Place’s trial and death sentence from the New York Journal.

The Trial and Historic Death Sentence

Martha Place’s July 1898 trial drew swarms of journalists eager to cover the “Brooklyn Murderess.” The New York Times described her as stoic, with a face “like a rat” that only shifted to a “sardonic grin” when William testified. The World noted, “Her face is not pleasant. She looks like a woman who has spent most of life fretting and worrying.” The evidence was damning: Martha’s own confession, the autopsy findings, and William’s testimony painted a picture of premeditated violence driven by jealousy. Found guilty of first-degree murder, she was sentenced to death, a verdict that stunned the nation due to its method—the electric chair, a relatively new invention used only on men since its debut in 1890.

Newspapers closely chronicled Martha Place’s final days in prison.

Martha’s legal team appealed to New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt for clemency, but he refused, stating, “My sympathies in criminal cases are for the wronged and not the wrongdoer,” per the Trentonian. The decision to execute a woman by electric chair was unprecedented, amplifying the case’s notoriety. As @NYHistory tweeted, “Martha Place’s trial wasn’t just about murder—it was a test of the electric chair’s limits. Could it handle a woman?” The public’s fascination with her crime and punishment underscored the era’s morbid curiosity about capital punishment’s new frontier.

The Execution: A Historic and Troubling Milestone

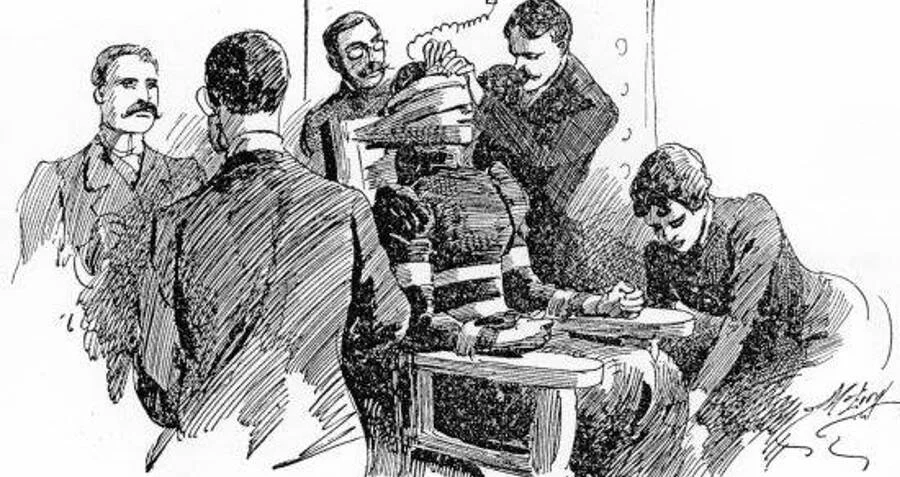

On March 20, 1899, Martha Place walked to the execution chamber at Sing Sing Prison, dressed in a black gown she made herself. Despite her hope for a last-minute reprieve, as noted by the Trentonian, she remained “reasonably composed.” The electric chair, first used on William Kemmler in 1890 with gruesome results (requiring two shocks), posed unique challenges for a female prisoner. Executioners, accustomed to men, struggled with Martha’s long, thick, graying hair, which had to be clipped for forehead electrodes, and her long skirt, which was slit to attach ankle electrodes discreetly, preserving her modesty.

Strapped into the chair, Martha’s final words were, “God help me.” A 1,760-volt shock ended her life seconds later at age 49. The San Francisco Call contrasted her calm with a previous female execution, noting, “The last woman condemned to die in this State went to the gallows shrieking and fighting, but Mrs. Place hardly uttered a sound.” Her execution marked a grim milestone as the first of 4,374 electric chair executions in the U.S. between 1890 and 2010, per a 2014 study. As @DeathPenaltyFacts posted, “Martha Place’s execution wasn’t just a punishment—it was a turning point in how America killed.”

Legacy of the “Brooklyn Murderess”

Martha Place’s story transcends her crime, embedding her in the history of capital punishment. Her execution highlighted the electric chair’s growing role as a method of execution, raising questions about its humanity and application to women. The logistical challenges—adjusting for her hair and attire—underscored the era’s inexperience with female executions, while her stoic demeanor contrasted with the sensationalized media portrayal of her as a cold-blooded killer. Her case, as @TrueCrimeTales shared, “shows how jealousy can destroy lives, but also how justice can be as brutal as the crime.”

Martha’s legacy endures as a cautionary tale of unchecked emotions and the harsh realities of justice in the late 19th century. Her mugshot from Sing Sing, widely shared online, and newspaper accounts from the El Paso Daily Herald and New York Journal keep her story alive, reminding us of the human cost of crime and punishment. While her actions were indefensible, her execution marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of capital punishment, influencing debates that continue today.

Martha Place’s journey from a troubled woman to the “Brooklyn Murderess” and the first woman executed by electric chair is a chilling chapter in American history. Her brutal murder of Ida Place, driven by jealousy, shocked the nation, while her execution underscored the complexities of applying new technology to justice. The haunting details—acid, an axe, and a historic electrocution—have fueled fascination on social media, where fans share her story as a blend of tragedy and horror. As we reflect on Martha’s life and death, we’re reminded of the thin line between human frailty and irreversible acts. Share your thoughts below: Was Martha Place a monster shaped by circumstance, or did her crime justify her grim fate? Let’s keep this dark tale alive as we explore the shadows of justice.

News

Kylie Jenner CONFRONTS North West for Stealing Her Fame — Is North Getting Surgeries?! – S

Kylie Jenner CONFRONTS North West for Stealing Her Fame — Is North Getting Surgeries?! The Kardashian-Jenner family is no stranger…

Glorilla EXPOSES Young Thug Affair After Mariah The Scientist Calls Her UGLY — The Messiest Rap Drama of 2024! – S

Glorilla EXPOSES Young Thug Affair After Mariah The Scientist Calls Her UGLY — The Messiest Rap Drama of 2024! If…

FEDS Reveal Who K!lled Rolling Ray: Natural Causes or Sinister Set Up? The Truth Behind the Internet’s Most Mysterious Death – S

FEDS Reveal Who Killed Rolling Ray: Natural Causes or Sinister Set Up? The Truth Behind the Internet’s Most Mysterious Death…

Eddie Griffin EXPOSES Shocking Agenda Behind North West’s Forced Adult Training – Is Kim Kardashian Crossing the Line? – S

Eddie Griffin EXPOSES Shocking Agenda Behind North West’s Forced Adult Training – Is Kim Kardashian Crossing the Line? The Internet…

Sexyy Red Sentenced to Death Over Trapping & K!ll!ng a Man: The Shocking Truth Behind the Entertainment Industry’s Darkest Scandal! – S

Sexyy Red Sentenced to Death Over Trapping & K!ll!ng a Man: The Shocking Truth Behind the Entertainment Industry’s Darkest Scandal!…

Unbelievable Discovery: Giant Dragon Skeleton Emerges in India! – S

Unbelievable Discovery: Giant Dragon Skeleton Emerges in India! A Flood Unveils the Impossible The world was stunned this September when…

End of content

No more pages to load