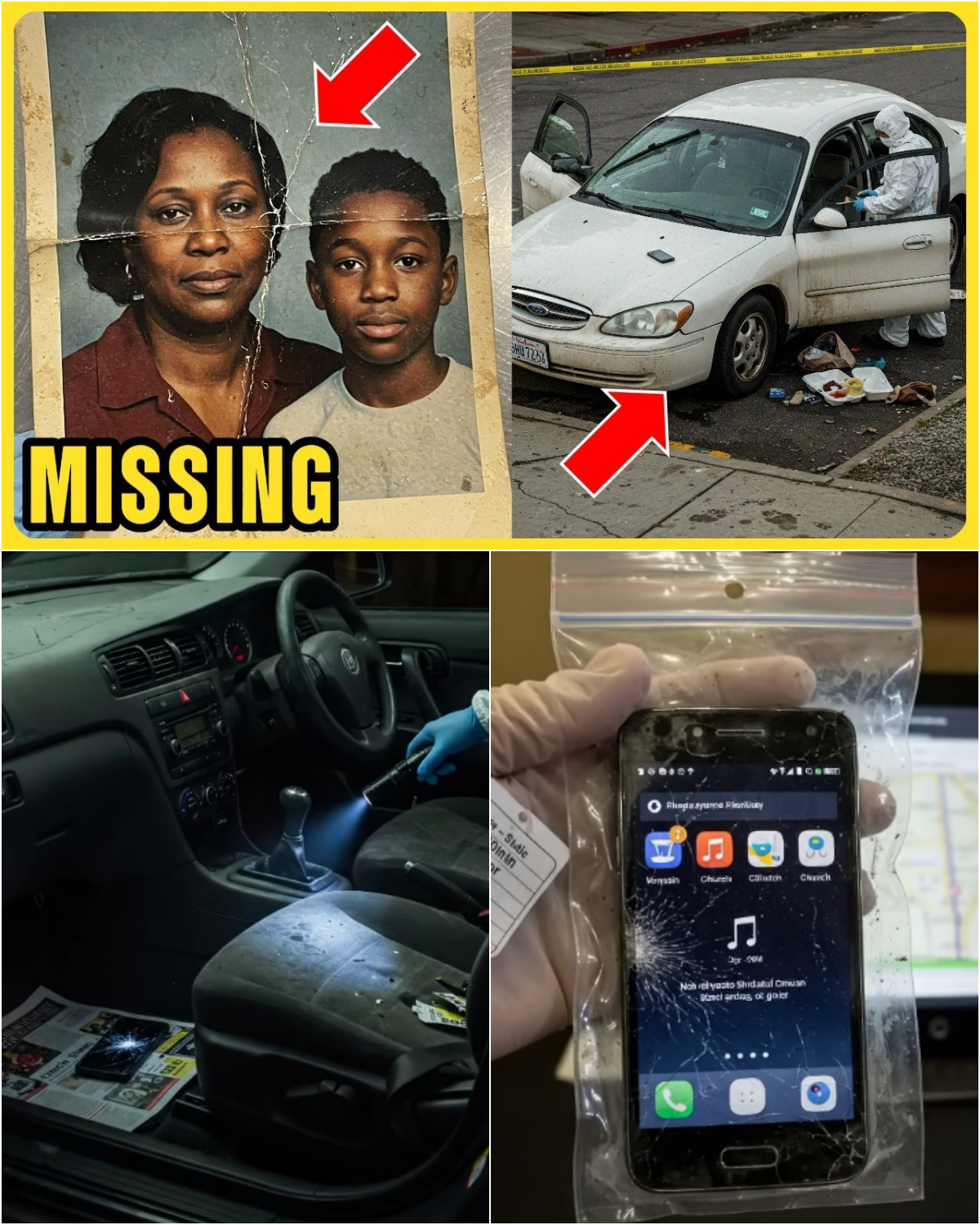

A Mother and Son Disappeared After Church — Then a Local Found Their Car Empty and Unlocked

Tamika Rollins stood in front of her hallway mirror on a bright Sunday morning, smoothing the collar of her 10-year-old son’s shirt. Dorian squirmed and grinned, clutching a plastic dinosaur in one hand and a slice of buttered toast in the other.

“Mama, can I bring T-Rex to church?” he pleaded.

Tamika smiled, brushed a crumb from his cheek, and kissed his forehead. “Only if he stays quiet during the sermon,” she said.

It was their ritual: get dressed, eat breakfast, and walk the few blocks to Morning Glory Baptist. Tamika’s mother, Loretta, usually came along, but today she stayed home with a cough. Tamika wore a cream dress with gold trim, her braids tied back with a satin ribbon. Dorian wore his favorite “grown-up” outfit—a navy vest, white shirt, and beige slacks.

Their white 2005 Ford Taurus waited under the sycamore tree, the engine quiet, the sun baking the hood. The car had seen better days, but it always got them where they needed to be.

Church was lively that morning. Deacon Hill sang too loud, Sister Leverne waved her handkerchief like she was fanning away the devil, and Reverend Moore preached about protecting your blessings. Tamika nodded along, holding Dorian’s hand while he doodled in the margins of the bulletin.

Afterward, they picked up lunch plates—fried chicken, cornbread, collard greens—and chatted in the parking lot. Dorian ran ahead, waving at his friend before climbing into the passenger seat. Tamika unlocked the doors, set her phone on the dashboard, and placed the food in the back seat. Witnesses later said it looked like any other Sunday.

But something was wrong.

By 5:00 p.m., Loretta was pacing her living room. She’d expected to hear the car hours ago. She called Tamika twice. No answer. Tried again—straight to voicemail. She peeked through the curtains, expecting to see them walking up the sidewalk, but the street stayed empty.

Sunset neared. Loretta called around. No one at church had seen them after the service. Dorian hadn’t texted his cousin. None of Tamika’s friends had heard from her. At 6:22 p.m., Loretta called the police. The dispatcher asked if maybe they’d run an errand. Loretta’s voice was tired but firm: “My daughter doesn’t just disappear.”

An hour later, police responded to a call about a car idling near Ninth and Bailey. The engine was still running, doors unlocked. Inside: two styrofoam lunch containers, still warm. A purse in the back seat. A cell phone face-down on the dashboard, screen cracked. In the passenger seat: a pair of small black dress shoes—Dorian’s.

No one was inside.

The street was mostly empty. Surveillance footage from a nearby liquor store showed only the car turning onto the block—no clear view of who got out. Police filed a report, noting no sign of struggle, no damage to the vehicle. No Amber Alert was issued. Loretta almost collapsed from rage. She pointed to the shoes. “Does that look normal to you?”

But the case was labeled a welfare check, not an emergency. They waited.

Loretta did not.

That night, she called Simone Keys, a local reporter who ran an independent blog covering underreported stories in East St. Louis. By 11 p.m., Simone had posted a breaking article: “Mother and Son Vanish After Church — Car Found Still Running, Child’s Shoes Left Behind.” She shared a photo Loretta gave her: Tamika and Dorian, all bright colors and wide smiles.

The post spread fast. By morning, hundreds had shared it. People left tips in the comments. One stood out: “Check the alley behind the old laundromat.” No name, just a sentence hanging in the air.

Simone sent the tip to Detective Randall Vicks, who found it waiting on his desk the next morning. The alley was two blocks from where the car had been found, not on the initial search grid. He marked it on a map and headed out.

He didn’t know it yet, but what waited behind that laundromat would change everything.

Detective Vicks arrived behind the boarded-up laundromat just after 9 a.m. The building was condemned, the alley cluttered with old mattress springs and broken tile. Two patrol officers had already taped off the area. A half-crushed church program lay in the gravel: “Dorian Rollins,” neatly typed on the cover.

Tire impressions curved along the gravel, then reversed out. Weeds were flattened in an arc, like something heavy had been dragged. No blood, no witnesses—just the weight of something wrong.

Loretta arrived an hour later, leaning on a cane, flanked by a neighbor. She saw the church program sealed in plastic and her knees buckled. “I ironed that dress for him myself,” she whispered. “He folded that paper up and put it in his vest pocket.”

Later that afternoon, Vicks sat with Loretta in her living room. She handed him a spiral notebook from Dorian’s backpack. One page showed a man with big shoulders and jagged teeth standing near a car. In a speech bubble, Dorian had written: “He smiled at me again.”

Loretta explained: “Dorian told me he saw a man watching the car when they came out of the grocery store. I told him, ‘Don’t talk to strangers.’ I didn’t think it meant anything.”

On another page, a sketch showed a woman and boy walking into a building with a cross on top. Below, the boy wrote: “Me and mama. He was still there. His teeth looked weird.”

It wasn’t a confession, but it was a shadow. And sometimes shadows point to predators.

Across town, Simone combed through tips. One name kept coming up: K. Milbour. The messages were inconsistent—some said he worked on cars, some said he was dead. Simone ran the name through public records and found a hit: Kenneth Milbour, last known address two blocks from the laundromat. Age 38. History of assault.

She found his mugshot from 2011: crooked teeth, sunken eyes, the same chin as the boy’s drawing. She sent everything to Vicks.

Minutes later, the lab called: fingerprints from the Taurus’s glove box and rear door matched a sealed juvenile file—Kenneth Milbour.

Vicks drove to Milbour’s last address. The house was empty, but a neighbor remembered him: “Used to stay there, always arguing with another man—Lonnie, lives behind the liquor store.”

Lonnie Gant had been interviewed the night the car was found. His story kept shifting. As Vicks dug into records, he found Lonnie and Milbour had once been arrested together, stripping copper from an abandoned church.

At a rundown motel, Vicks confronted Lonnie. Under pressure, Lonnie admitted: “He told me to help. Said it was family. The woman had lost her mind and the boy was his.” He described driving Milbour out to Belleville, to an old farmhouse behind a barn.

A task force traced the property. The house was empty, but inside: a torn women’s dress, a shoelace, an empty water jug. Scratch marks on the door frame. A fingerprint on the jug matched Tamika’s. She had been alive within the last 48 hours.

But there was no sign of Dorian.

That night, a nurse at a local hospital noted a strange occurrence: a woman dropped off by an anonymous caller, no ID, dirty clothes, barely conscious. When they tried to check her in, she whispered two words: “My son.”

Tamika had returned, but the boy was still gone.

Detective Vicks got the call. At the hospital, Tamika lay motionless, her lips cracked, her hair matted. Nurse Patrice Freeman sat nearby.

“Miss Rollins, can you hear me?” Patrice asked.

Tamika’s eyes opened, distant. Her fingers twitched at her throat—her necklace was gone. She let out a soft whimper and turned to the wall.

Later, Tamika whispered: “You took my baby.”

“Who did?” Patrice asked.

“I never saw his face. He wore a hoodie. Always kept the light off. He had gloves.” Her voice was like paper tearing. “After church, I saw him by the alley. He was staring. I got in the car. Then, in the back seat—he was there. He had a knife. Told me to drive. Said if I screamed, he’d hurt Dorian. Made me park near the laundromat. Then he made me walk. Took us to that house, the basement, tied me. Said Dorian would be fine if I cooperated. But two nights later, I heard my baby scream. Then he was gone.”

She cried. “He kept saying, ‘My boy.’”

A new witness came forward: Daryl Samson, who lived next to the laundromat, heard shouting in the alley two nights before the car was found. Two men arguing: “You better not mess this up again.” “She don’t even know who I am.”

Vicks mapped the route: from the laundromat alley to Taylor Street, to the farmhouse. It wasn’t random. This man had stalked Tamika, used people like Lonnie to cover his tracks.

Vicks drove Lonnie to Belleville. They found a shack behind a forgotten barn. Inside, Tamika was slumped against the wall, wrists bruised, mouth dry and split. She blinked as the light touched her face. “Please,” she rasped, “my son.”

Medics rushed in. Tamika was stabilized, but taken straight to critical care. Loretta arrived, breathless. “She kept that boy alive,” Loretta said. “So you keep her alive.”

But at 10:17 a.m., a flatline echoed through the ICU. Tamika Rollins died with her son’s name on her lips.

Dorian was still missing.

Vicks returned to the abandoned house on Bailey Street. In a floor crack, he found a mud-streaked notebook. Three pages used. The first was blank. The second, a drawing of a boy under a cloud. The third, a note in messy handwriting: “He said I had to be quiet. He said Mama made him angry. He said I’m his now.”

A tip led police to a gas station near Centerville. A boy was spotted, dirty, alone, holding a missing flyer. “Dorian,” Vicks called. The boy looked up, glassy-eyed. “I’m not his anymore,” he mumbled.

“No, you’re not,” Vicks said, wrapping him in his coat. “You’re safe. We’re going to take you home.”

The funeral for Tamika Rollins was held six days later. Hundreds came—neighbors, church members, nurses, strangers, all dressed in white. On the casket lay Dorian’s crumpled drawing: a stick-figure boy and a tall woman under a sun, with the word “us” above them.

A mural was painted two weeks later on the side of the laundromat: Tamika holding her son’s hand, walking toward a beam of light. Above them: “She didn’t make it home, but she made sure he did.”

Dorian didn’t speak for the first three days after the funeral. At night, Loretta found him curled on the couch, holding a flashlight in one hand, the other buried in the sleeve of Tamika’s old hoodie. He never cried. Neither did Loretta—not in front of him.

She called a trauma counselor, Miss Reena, who brought drawing pads and clay. Dorian didn’t touch them. He stared out the window at the mural. On the first page of a new sketchbook, he drew a sun, a house, a small stick figure alone in a yard, and wrote the word “waiting.” It was the first thing he’d written since coming home.

Police confirmed the abductor: Kenneth Milbour, age 38, a former acquaintance of Tamika’s from her late teens. Investigators learned Milbour believed Dorian was his biological son. There was no proof, no relationship—just obsession. He’d followed Tamika’s life from the shadows, waiting for the right Sunday.

Milbour was found hours later in a motel bathroom, dead by suicide. He never confessed, never explained, never faced the woman he stole from the world.

Loretta didn’t care. “Let the devil bury his own,” she said. “We don’t speak his name in this house.”

Months passed. Dorian began speaking again—slowly, carefully, as if language was something fragile. On his eleventh birthday, he stood in front of the mural with Simone and Miss Reena. The mayor made a speech about healing. But it was Dorian who silenced the block. He stepped to the microphone, voice a whisper: “She told him I wasn’t his,” he said. “She was right.” Then he looked up at the mural, chin rising. “She’s still mine.”

The white Ford Taurus was eventually donated to a domestic violence shelter. The mural stayed, even as the laundromat collapsed. The community preserved the wall, built a garden in front, installed a bench with Tamika’s name.

And every Sunday, Loretta and Dorian walk past it on their way to church. He still carries the same flashlight. She still carries the same grief. But they walk forward—always forward—just like Tamika taught them.

News

Kylie Jenner CONFRONTS North West for Stealing Her Fame — Is North Getting Surgeries?! – S

Kylie Jenner CONFRONTS North West for Stealing Her Fame — Is North Getting Surgeries?! The Kardashian-Jenner family is no stranger…

Glorilla EXPOSES Young Thug Affair After Mariah The Scientist Calls Her UGLY — The Messiest Rap Drama of 2024! – S

Glorilla EXPOSES Young Thug Affair After Mariah The Scientist Calls Her UGLY — The Messiest Rap Drama of 2024! If…

FEDS Reveal Who K!lled Rolling Ray: Natural Causes or Sinister Set Up? The Truth Behind the Internet’s Most Mysterious Death – S

FEDS Reveal Who Killed Rolling Ray: Natural Causes or Sinister Set Up? The Truth Behind the Internet’s Most Mysterious Death…

Eddie Griffin EXPOSES Shocking Agenda Behind North West’s Forced Adult Training – Is Kim Kardashian Crossing the Line? – S

Eddie Griffin EXPOSES Shocking Agenda Behind North West’s Forced Adult Training – Is Kim Kardashian Crossing the Line? The Internet…

Sexyy Red Sentenced to Death Over Trapping & K!ll!ng a Man: The Shocking Truth Behind the Entertainment Industry’s Darkest Scandal! – S

Sexyy Red Sentenced to Death Over Trapping & K!ll!ng a Man: The Shocking Truth Behind the Entertainment Industry’s Darkest Scandal!…

Unbelievable Discovery: Giant Dragon Skeleton Emerges in India! – S

Unbelievable Discovery: Giant Dragon Skeleton Emerges in India! A Flood Unveils the Impossible The world was stunned this September when…

End of content

No more pages to load