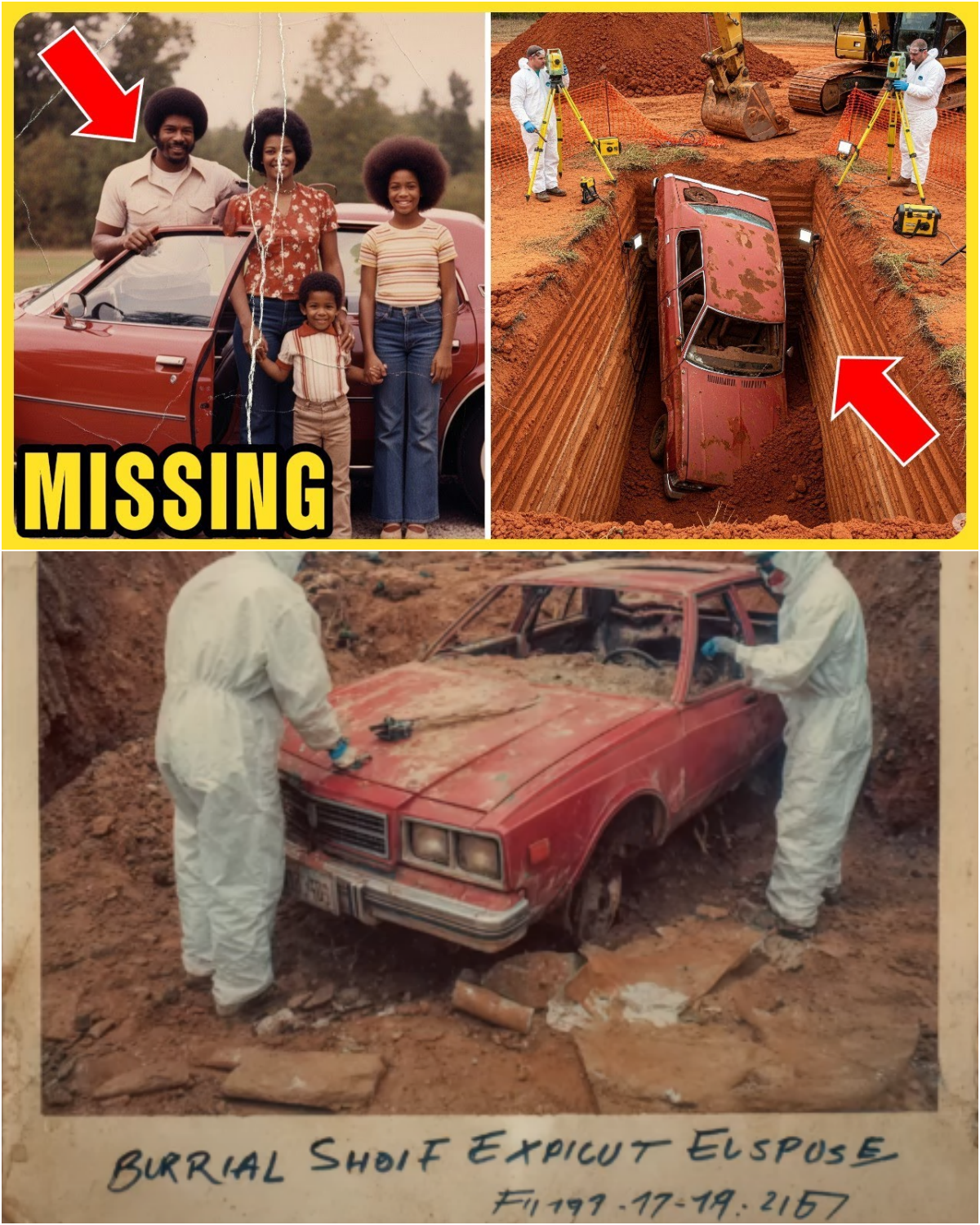

A Black Family Vanished in Their New Car in 1977—20 Years Later It Was Found Buried Vertically

The disappearance of the Westmore family in the summer of 1977 was, for two decades, a whispered legend in rural Georgia. It was a story told in barbershops and kitchens, always with a shake of the head and a quiet, uneasy glance at the horizon. A black family, Arthur and Eleanor Westmore and their children Kimberly and Michael, drove away in their brand new sedan for a Sunday picnic—and were never seen again. The local sheriff’s file was thin, dismissive, and soon forgotten. It wasn’t until 1997, when a highway survey crew’s ground-penetrating radar struck something twenty feet beneath the red Georgia clay, that the truth began clawing its way back to the surface.

What they found was not just a car, but a tomb: the 1977 sedan, nose pointed straight at the planet’s core, buried vertically in the earth—a silent, impossible monument to a vanished family.

The Impossible Puzzle

Detective Lena Morris of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation’s Cold Case Unit was used to tragedy, but the Westmore case was something else. It landed on her desk not as a file, but as a riddle. The car’s twisted, mud-caked shell was hoisted onto a steel platform in the GBI’s forensics bay, its paint and chrome erased by decades of pressure and clay. Inside, the skeletal remains of four people—Arthur, Eleanor, Kimberly (14), and Michael (8)—sat in the same seats they’d occupied twenty years before.

The logistics were staggering. The vertical burial required heavy machinery, meticulous planning, and secrecy. This wasn’t a crime of rage. It was a construction project. The original investigation, a dozen pages of racist assumptions and lazy police work, had concluded the Westmores “probably moved on.” Now, the truth was clear: they’d been executed and hidden in a way meant to taunt anyone who might ever care.

Detective Morris needed help. She reached out to the one man in Georgia with a reputation for solving the unsolvable: Alistair Finch, a retired legend of the GBI. Finch, now in his late 60s, was a sharp-eyed, soft-spoken man whose mind worked like a lockpick on the puzzles of human evil. He agreed to consult, and the game was afoot.

Ghosts of 1977

Finch’s first move was to meet the only surviving Westmore—Caleb, now 39, who, by a twist of fate, had been at a cousin’s house the day his family vanished. Caleb returned to Georgia with a storm of emotions. Finch, with quiet empathy, asked him to recall not just the day, but the months leading up to the disappearance: the pride of Arthur, the warmth of Eleanor, the dreams of Kimberly, the innocence of Michael. And the tensions—racial lines never crossed, the simmering land dispute with the powerful Harrington family, and the quiet threats that had always hung in the air.

Finch listened, fingers steepled, eyes never leaving Caleb’s face. “You are the most important piece of this puzzle,” he said. “Now, let’s find the others.”

Drawing the Circle

Finch’s strategy was to reconstruct the world of 1977, treating the case as a live crime. He and Morris assembled a list of suspects:

The Harringtons: Clayton and Meil, sons of the county’s most powerful family, locked in a land dispute with Arthur.

Thomas Randall: A white businessman, bitter after losing a carpentry contract to Arthur.

Walter Bishop: A family friend rumored to be infatuated with Eleanor.

Silas Black: A distant, resentful cousin who believed the land should have been his.

Each had a motive. Each had secrets. And all, as Finch would soon discover, had alibis that seemed too perfect.

The Interviews

One by one, the suspects were brought in. Each interview was a séance, conjuring the ghosts of a Georgia summer long past.

Randall claimed he was at a church retreat in Savannah, his alibi backed by a dozen witnesses. Yet he let slip details about the Westmores’ car that only someone who’d seen it up close would know.

Bishop, frail and teary, produced a doctor’s note for an illness that weekend, but hinted at marital strife in the Westmore home—a lie, Caleb insisted.

Silas Black was all rage and resentment, his alibi a solo fishing trip no one could confirm. But Finch sensed in him not the cold cunning needed for such a crime, but something smaller, pettier.

The Harringtons, flanked by lawyers, radiated arrogant denial. Their alibi? The same church retreat as Randall, corroborated by the same circle of powerful friends.

“It’s a web,” Morris said, frustrated, staring at the evidence board. “Everyone’s lying about something.”

Finch, however, was focused elsewhere. He stared at the photos of the car, not the suspects. “We’ve been so focused on the people,” he said quietly, “that we’ve forgotten to listen to the car. The car cannot lie.”

The Car’s Testimony

Finch spent hours with the forensics reports, ignoring the suspects’ stories. He fixated on the odometer: 18.7 miles. The car, brand new, had only been driven a total of 15.7 miles since it left the dealership. Mapping every possible route the Westmores might have taken—home, church, grocery store, the inherited land—Finch realized the car had made only one real trip: from home, to church, to the remote property where it was found.

The fuel gauge was nearly full. The license plate bolts were freshly scratched; someone had removed and replaced the plate. “The car wasn’t driven to its grave,” Finch explained to Caleb. “It was transported—probably on a flatbed truck from the Harringtons’ construction company. They removed the plate for a temporary transport tag, then reattached it before burial.”

The crime, Finch concluded, was not a murder of passion but an orchestrated, logistical project—requiring heavy equipment, precise planning, and the power to keep it secret for decades. Only the Harringtons fit the bill.

The Final Confrontation

Detective Morris called all the suspects into a conference room. Finch, standing before a projected photo of the vertical car, laid out the logic piece by piece: the odometer, the fuel, the license plate, the construction equipment, and the .38 revolver shell found in the car—traced to the Harringtons’ violent foreman, Jebidiah Thorne, now deceased.

“You claimed to be 200 miles away in Savannah,” Finch said to the Harrington brothers, “but the car tells a different story. The murder was local. Your alibi is a lie. The evidence is irrefutable.”

Clayton Harrington’s face was stone. Meil, the younger brother, broke down in sobs. The illusion of power had been shattered.

Justice, At Last

The trial was a reckoning for the entire county. The Harringtons, their fortunes drained by lawyers, insisted their late father and his foreman acted alone. But the chain of evidence—constructed by Morris, guided by Finch, and anchored by Caleb’s memory—was unbreakable. The jury’s guilty verdict came swiftly. The Harrington brothers were sentenced to life, their empire of silence finally broken.

A week after the verdict, Caleb sat with Finch on a quiet veranda, watching the tide roll in. “Why was my father clutching that wooden bird I made him?” he asked.

Finch smiled gently. “Because, in his final moments, faced with evil, your father reached not for a weapon, but for a symbol of your love. It was not a clue for us, but a message for himself—a reminder that even in darkness, there is something pure worth holding on to.”

For the first time in 20 years, Caleb felt not just the cold satisfaction of justice, but the enduring warmth of grace.

News

Kylie Jenner CONFRONTS North West for Stealing Her Fame — Is North Getting Surgeries?! – S

Kylie Jenner CONFRONTS North West for Stealing Her Fame — Is North Getting Surgeries?! The Kardashian-Jenner family is no stranger…

Glorilla EXPOSES Young Thug Affair After Mariah The Scientist Calls Her UGLY — The Messiest Rap Drama of 2024! – S

Glorilla EXPOSES Young Thug Affair After Mariah The Scientist Calls Her UGLY — The Messiest Rap Drama of 2024! If…

FEDS Reveal Who K!lled Rolling Ray: Natural Causes or Sinister Set Up? The Truth Behind the Internet’s Most Mysterious Death – S

FEDS Reveal Who Killed Rolling Ray: Natural Causes or Sinister Set Up? The Truth Behind the Internet’s Most Mysterious Death…

Eddie Griffin EXPOSES Shocking Agenda Behind North West’s Forced Adult Training – Is Kim Kardashian Crossing the Line? – S

Eddie Griffin EXPOSES Shocking Agenda Behind North West’s Forced Adult Training – Is Kim Kardashian Crossing the Line? The Internet…

Sexyy Red Sentenced to Death Over Trapping & K!ll!ng a Man: The Shocking Truth Behind the Entertainment Industry’s Darkest Scandal! – S

Sexyy Red Sentenced to Death Over Trapping & K!ll!ng a Man: The Shocking Truth Behind the Entertainment Industry’s Darkest Scandal!…

Unbelievable Discovery: Giant Dragon Skeleton Emerges in India! – S

Unbelievable Discovery: Giant Dragon Skeleton Emerges in India! A Flood Unveils the Impossible The world was stunned this September when…

End of content

No more pages to load