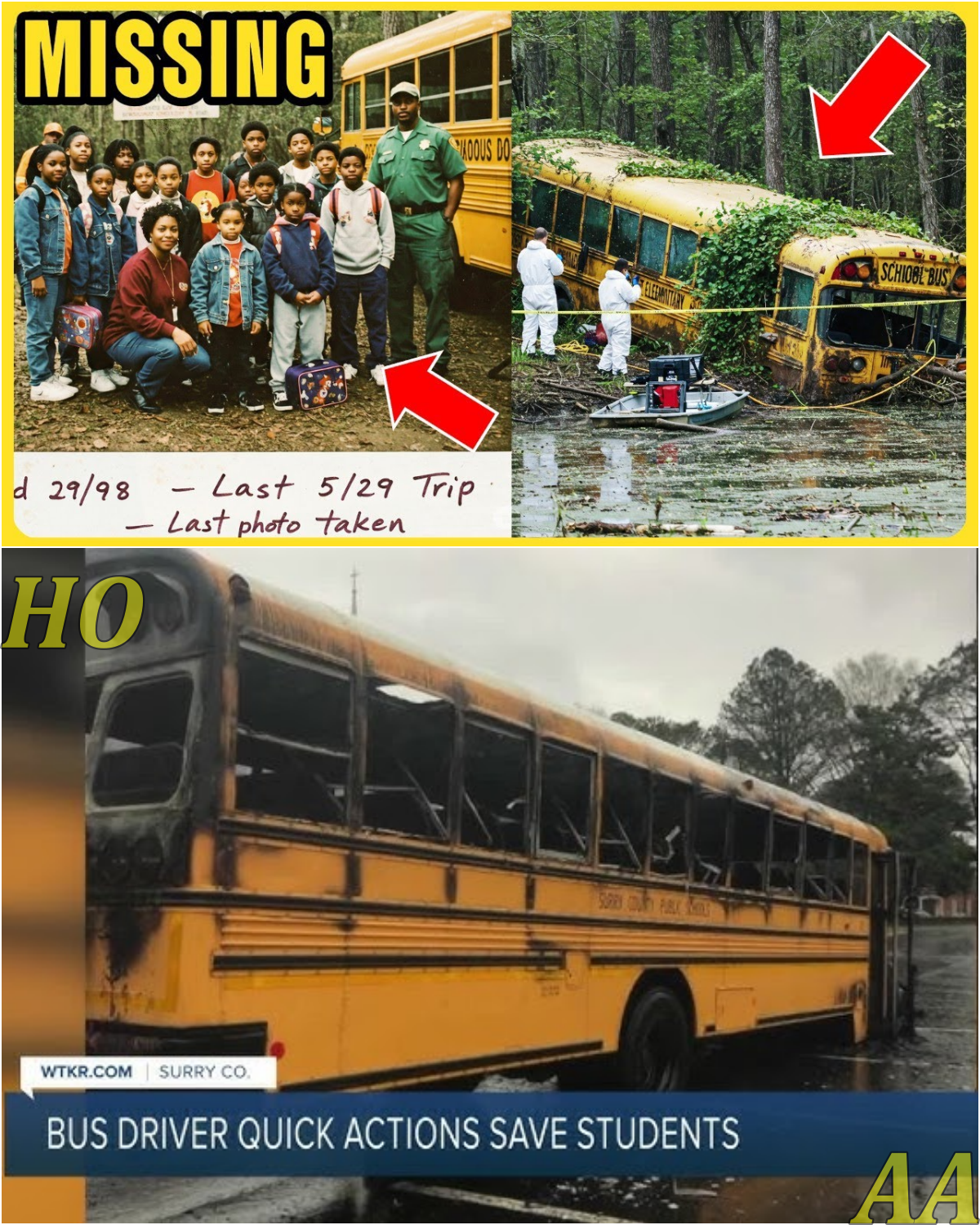

14 Students Went on a School Trip and Never Came Back — 10 Years Later, the Bus Was Found in a Swamp

Ten years ago, a yellow school bus carrying 14 Black children, their teacher, and a driver vanished during what should have been a routine field trip in rural Louisiana. The school denied the trip ever happened. The case was closed as a runaway. No Amber Alert, no search, no justice. This morning, that same bus was pulled from a Louisiana swamp, half-submerged, windows cracked, a small handprint still pressed to the glass.

The Vanishing

Denise Warren stood at the edge of Bayou Chang, her shoes sinking into the wet earth. Sunlight glinted off the rusted roof of a school bus jutting out from the reeds. Ten years had passed since she last saw her daughter, Jada, wave goodbye from the steps of that bus. Ten years since anyone had seen any of the 14 children, their beloved teacher Ms. Daniels, or the quiet driver, Mr. Hopkins.

It was 2014. Jada was just 11, excited for her field trip to the Lake View Cultural Center. Denise packed her favorite snacks, tied her braids, and kissed her forehead. Jada grinned, clutching her dinosaur keychain for luck. “We’re going to the lake, Mama. Ms. Daniels says it’s like a museum for heroes!” That was the last time Denise saw her daughter.

The bus never returned. At first, parents assumed a delay. By nightfall, panic set in. By midnight, desperate families gathered at the school, demanding answers. Only Officer Maurice Pickkins showed up, yawning through his notepad. “Kids run off all the time,” he said. “They’ll come back.” Denise nearly lunged at him. Jada wasn’t a runaway. None of them were.

No Amber Alert. No search teams. The news ran a three-minute segment and moved on. When parents confronted Principal Charlene Moss, she denied the trip was ever approved. She claimed the children never left campus. But Denise had proof: a group photo Ms. Daniels texted at 10:12 a.m., 9 miles southeast of the school. After the disappearance, the photo vanished from every parent’s phone—deleted remotely. Only Denise had a printed copy.

For the next decade, Denise became “the mother who couldn’t let go.” She kept Jada’s room untouched, attended every school board meeting, collected every scrap of evidence. She wasn’t alone. Simone Bellamy, a young journalist, lost her job for asking too many questions—about missing logs, broken cameras, and a police report filed just six hours after the kids vanished.

The Bus in the Swamp

Yesterday, Simone received an anonymous message: a GPS coordinate and a photo of a bus, half-submerged in swamp water. She called Denise. Before police could interfere, Denise drove straight there. Search crews winched the bus from the muck. The door was rusted shut; a crowbar pried it open. No bodies. No bones. Just the shell of a bus lost in time.

Inside: a child’s handprint on the rear window, preserved by silt. Ms. Daniels’ red lanyard, her ID still clipped on. Behind the driver’s seat, a Ziploc bag taped to the frame—children’s drawings, faded but intact. One showed a circle of trees and a building labeled “new place.” Another, a winding road marked “no trespassing.” The last: a crude map of the swamp, with “Our real trip” scrawled in orange crayon.

Denise clutched the map to her chest. Not Lake View. Not the museum. Someone had rerouted that bus—and someone had covered it up.

The Cover-Up

Detective Lance Morrow hadn’t planned to get involved. He thought it was just another cold case. But when he saw the photo of the smiling kids, the “Lake View or Bust” sign, he stopped cold. The case file was nearly empty—no reports, no evidence, just a single sheet marked “Closed: Runaway Youth, Field Trip Unconfirmed,” signed by Officer Pickkins, who’d retired five years earlier.

Morrow dug deeper. The school’s field trip calendar for 2014 was wiped clean. Transportation records missing. But in a forgotten cabinet, he found a paper backup: the original trip request, signed and approved by Principal Moss. When Morrow confronted her, she claimed forgery. “Ms. Daniels acted outside protocol,” she insisted. “She vanished. There was no point in wasting resources on an adult who may have fled prosecution.” But the signature matched Moss’s contract.

That night, Morrow stared at the children’s hand-drawn map, overlaying it with local landmarks. One trail aligned with a real swamp road, closed for years. Then his phone buzzed: an anonymous text, a scan of a letter from Ms. Daniels to the school board. “I am concerned about the rerouting of our field trip. This is not educational. It is being arranged by outside parties. I am requesting an alternate destination.” The letter was never filed.

The Church and the Land

Franklin Community Church sat just beyond the edge of town, white paint fading, windows sagging. Pastor Elijah Franklin admitted he’d suggested an “alternative location”—a site being considered for educational development. “A man named Victor Braxter, from Conway and Braster Development, said if the kids visited, it would help justify the zoning change.” Two days after the trip, Franklin received a call: “They were never meant to go that far. Forget it. If you value your congregation, move on.”

Morrow found zoning records: a permit filed for a private camp facility, land owned by the church, denied for “environmental risk.” Conway and Braster went bankrupt soon after. The swamp reclaimed its secrets.

The Witness

A tip led Morrow to Kenny Riy, a swamp trapper. In 2014, Kenny saw men in construction vests dumping barrels and bags in the swamp. He saw the bus, half-backed into the water. A woman with curly hair—Ms. Daniels—argued with the men, pointing at the children. “You should have kept your mouth shut,” one man yelled. Kenny heard a bang, then she was gone. The men pushed the bus deeper into the swamp. Kenny never reported it. “Who’d listen to a Black kid missing and a white man with no address?” he said. “They’d arrest me before asking questions.”

The night after Kenny spoke to Morrow, his trailer burned to the ground.

Evidence and Revelations

The bus yielded more secrets: four small children’s teeth beneath the driver’s seat—three matched to missing students. Behind the lining, Ms. Daniels’ journal: lesson plans, then frantic entries. “They changed the destination again. I told Charlene I wouldn’t take them unless I got a clear answer. There’s a man waiting near the church road. If anything happens, look in the clearing near the old cross. I can’t protect them all, but I’ll try.”

A construction worker’s map led to a concrete slab in the woods, two miles from the bus. Underneath: a hollow chamber. Inside, 14 pairs of shoes, snack wrappers, torn notebook pages. On the wall, in chalk: “She told us to be brave.” No bodies. No signs of escape.

Simone aired Ms. Daniels’ voicemail: “Charlene changed the location again. The address isn’t even on a map. There’s nothing there. I don’t feel right about this. I’m going to take pictures just in case.” The story went national.

The Final Clues

A crate in a storage unit, paid in cash for ten years, held dozens of Polaroids: the children smiling, playing, in the woods, on the bus, in the hidden chamber. In one, Ms. Daniels knelt beside Jada, wrapping her in a blanket. The last photo showed the group in front of a crooked sign: “Franklin Community New Beginnings Youth Project.” Two men in vests stood in the background. One, clipboard in hand, was Officer Maurice Pickkins.

No arrests. No charges. Pickkins had vanished, pension transferred to an offshore account. The company dissolved, the money scattered. The story, officials said, was a “tragedy,” a “systemic failure.” But Denise Warren knew better.

Refusing to Forget

At a vigil, Denise spoke: “They thought we’d forget. They thought if they buried the truth deep enough, we’d give up. But here we are, still standing, still fighting.” Simone read every name: Ariel James, Kam Carter, Jada Warren, Terrell Smith, Nia Franklin, Zire Owens, Malik Harris, Destiny Ford, Lamar Brisco, Trinity Knox, Elijah Johnson, Monique Bell, Rashad Green, Zoe Carter, Ms. Bernice Daniels, Mr. Clay Hopkins. For each name, a bell rang, echoing across the park.

The Legacy

Days later, an investigative journalist uncovered that Conway and Braster had filed for educational exemptions across the South, always for swamp land, always withdrawn when denied—except in Louisiana, where bus 72 was found. One subcontractor was a former sheriff’s deputy from the same parish as Officer Pickkins.

Simone compiled everything—photos, journal entries, voicemails—into a documentary: The Names They Tried to Bury. It ended with Jada’s drawing, “Our real trip,” and her voice: “My name is Jada Warren. I like dinosaurs and peanut butter sandwiches and my teacher, Ms. Daniels. When I grow up, I want to help people remember.”

That night, Denise sat in Jada’s room, wrote every child’s name, every memory, every birthday missed. And one final line:

I remember you. I always will.

Two days later, another anonymous tip arrived. It wasn’t about the children. It was about a warehouse, filled with sealed files, unmarked tapes, and a list of other schools.

This wasn’t the first time. And it would not be the last.

News

Kylie Jenner CONFRONTS North West for Stealing Her Fame — Is North Getting Surgeries?! – S

Kylie Jenner CONFRONTS North West for Stealing Her Fame — Is North Getting Surgeries?! The Kardashian-Jenner family is no stranger…

Glorilla EXPOSES Young Thug Affair After Mariah The Scientist Calls Her UGLY — The Messiest Rap Drama of 2024! – S

Glorilla EXPOSES Young Thug Affair After Mariah The Scientist Calls Her UGLY — The Messiest Rap Drama of 2024! If…

FEDS Reveal Who K!lled Rolling Ray: Natural Causes or Sinister Set Up? The Truth Behind the Internet’s Most Mysterious Death – S

FEDS Reveal Who Killed Rolling Ray: Natural Causes or Sinister Set Up? The Truth Behind the Internet’s Most Mysterious Death…

Eddie Griffin EXPOSES Shocking Agenda Behind North West’s Forced Adult Training – Is Kim Kardashian Crossing the Line? – S

Eddie Griffin EXPOSES Shocking Agenda Behind North West’s Forced Adult Training – Is Kim Kardashian Crossing the Line? The Internet…

Sexyy Red Sentenced to Death Over Trapping & K!ll!ng a Man: The Shocking Truth Behind the Entertainment Industry’s Darkest Scandal! – S

Sexyy Red Sentenced to Death Over Trapping & K!ll!ng a Man: The Shocking Truth Behind the Entertainment Industry’s Darkest Scandal!…

Unbelievable Discovery: Giant Dragon Skeleton Emerges in India! – S

Unbelievable Discovery: Giant Dragon Skeleton Emerges in India! A Flood Unveils the Impossible The world was stunned this September when…

End of content

No more pages to load