-

2025 Celebrity Engagements

2025 Celebrity Engagements Gina Kirschenheiter & Travis Mullen The Real Housewives of Orange County star and the entrepreneur got engaged…

-

Man, 76, who kidnapped five-year-old girl and fed her to ALLIGATORS faces death penalty

Man, 76, who kidnapped five-year-old girl and fed her to ALLIGATORS faces death penalty A Florida man who kidnapped a…

-

Michael Jackson’s Death, a Cryptic Warning, and the Resurfacing of a Hollywood Conspiracy

Michael Jackson’s Death, a Cryptic Warning, and the Resurfacing of a Hollywood Conspiracy When Michael Jackson announced his final comeback…

-

Cardi B Explodes at Tasha K as Legal Tensions Resurface Over New Allegations

Cardi B Explodes at Tasha K as Legal Tensions Resurface Over New Allegations Cardi B and controversial blogger Tasha K…

-

Jennifer Lawrence cuts a svelte figure at Die My Love screening as she shakes off shock SAG Actor Awards snub

Jennifer Lawrence cuts a svelte figure at Die My Love screening as she shakes off shock SAG Actor Awards snub…

-

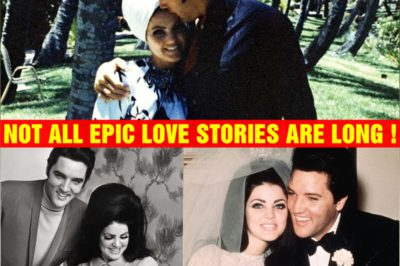

The Heartbreaking Truth About Elvis Presley and Priscilla Presley’s Love Story

The Heartbreaking Truth About Elvis Presley and Priscilla Presley’s Love Story Marriage to Elvis Presley was ultimately untenable, but Priscilla…

-

Man Reported His Wife Missing — 10 Years Later, Detectives Found Her Locked in Their Own Basement | HO”

Man Reported His Wife Missing — 10 Years Later, Detectives Found Her Locked in Their Own Basement | HO” Anthony…

-

Cop Kills His Mistress Because She Contacted His Wife About Their Affair | HO”

Cop Kills His Mistress Because She Contacted His Wife About Their Affair | HO” A Promising Life in Edgbaston…

-

Houston Gang Member EXECUTES Ex GF’s 9YO DAUGHTER As REVENGE For Her “Breaking Up With HIM” | HO”

Houston Gang Member EXECUTES Ex GF’s 9YO DAUGHTER As REVENGE For Her “Breaking Up With HIM” | HO” Jeremiah Jones…

-

She Taught Him Everything — Then $96,000 Was Gone | HO”

She Taught Him Everything — Then $96,000 Was Gone | HO” William Todd Austin was from Bojer City, Louisiana. He…

-

He Preached for Christmas — Then His Wife 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐭 Him in the Eye. | HO”

He Preached for Christmas — Then His Wife 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐭 Him in the Eye. | HO” A Pastor With a Public…

-

Jennifer Garner makes rare heartbreaking comments about ‘hard’ Ben Affleck divorce that ended ‘true friendship’

Jennifer Garner makes rare heartbreaking comments about ‘hard’ Ben Affleck divorce that ended ‘true friendship’ Jennifer Garner has made the…

-

MY FATHER DIDN’T INVITE ME HOME FOR CHRISTMAS.

MY FATHER DIDN’T INVITE ME HOME FOR CHRISTMAS They said I was “busy with work.” So I stayed silent. THREE…

-

Wife Won $50M Lottery & Divorced Her Husband Without Telling Him – 5 Years Later he Discovered Why | HO”

Wife Won $50M Lottery & Divorced Her Husband Without Telling Him – 5 Years Later he Discovered Why | HO”…

-

INSTANT REGRET Hits Corrupt WTA Referee After BLAMING Coco Gauff For PLAYING FAST! | HO”

INSTANT REGRET Hits Corrupt WTA Referee After BLAMING Coco Gauff For PLAYING FAST! | HO” It was supposed to be…

-

The Cheating Wife 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her Husband, A Pizza Maker, For A $100,000 Insurance Payout | HO”

The Cheating Wife 𝐏𝐨𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 Her Husband, A Pizza Maker, For A $100,000 Insurance Payout | HO” Part 1 — A…

-

The Husband Runs Over His Cheating Wife And Her Lover With A Truck | HO”

The Husband Runs Over His Cheating Wife And Her Lover With A Truck | HO” Part 1 — The Marriage,…

-

Fall Crazy in Love With Beyoncé’s Mom Life Raising Blue Ivy, Rumi and Sir Carter

Fall Crazy in Love With Beyoncé’s Mom Life Raising Blue Ivy, Rumi and Sir Carter Beyoncé is leading by example…

-

He Warned Her That If She 𝐆𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐖𝐞𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭 After The Wedding, He Would 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐭 Her — And He Did | HO”

He Warned Her That If She 𝐆𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐖𝐞𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭 After The Wedding, He Would 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐭 Her — And He Did |…

-

Sydney Sweeney lands another career-saving role after string of box office bombs and scandals

Sydney Sweeney lands another career-saving role after string of box office bombs and scandals Things are finally looking up for…