My Mom Went to Canada for a Month, Left Me With $3 at Age Eleven— When They Returned I…

The beam from a police flashlight slid across our front porch like it was searching for something we’d tried to hide in plain sight.

My mother stood frozen at the end of the driveway, designer luggage still in her hands, vacation tan still on her skin, airport perfume still clinging to her like a lie. The taxi driver hovered behind her, polite and confused, one hand halfway raised as if to ask a question he already regretted.

“Ma’am?” he said carefully. “You still want help with the bags?”

She didn’t answer.

She couldn’t.

Because what she was looking at—what she was finally being forced to look at—wasn’t a messy house or an angry teenager or a bratty kid brother.

It was consequence.

But I’m jumping ahead.

Let me take you back to the morning that changed everything—the morning my own mother placed **$30** on the kitchen counter, set down a single bottle of water like it was a joke, and vanished for the entire summer.

My name is Kristen Harrison. I was eighteen, fresh out of high school, and I thought I knew what hard times looked like.

I was wrong.

My mother, Valerie, was the kind of woman who needed a man like she needed oxygen—like the air would thin if she wasn’t wanted by someone, even if that someone came with a cost the rest of us had to pay.

My dad left when I was seven. My little brother Nolan was still a baby. I barely remember my father’s face clearly, but I remember the sound of the door. I remember the way the house felt afterward, like it had exhaled and never inhaled again.

After that came the parade of boyfriends.

A car salesman who stayed eight months. An accountant who lasted a year. A fitness instructor who moved in for three weeks and ate all our food before disappearing with our microwave.

Yes, our microwave.

I still don’t understand that one, but I learned early that when adults want something, they don’t always care if it was yours first.

Through it all, I raised myself. And when Nolan got old enough to need more than cereal and cartoons, I raised him too.

Mom was always too busy chasing her next romantic adventure to notice her kids needed things like dinner, clean clothes, rides to school, someone to show up at parent-teacher conferences, someone to remember that “summer” doesn’t mean bills take a vacation.

Then she met Boyd Carpenter.

Online, in April.

Wealthy. Charming. Vancouver.

Within weeks, she was flying to see him every other weekend, staying longer each time, leaving me “a few dollars” to handle things like groceries, Nolan, and the illusion of stability.

By June, I knew this one was different—not because Boyd was better, but because Mom was worse. She talked about him like he was a prince from a fairy tale, like the universe finally owed her something shiny.

Then came July 3rd.

That morning started with a sound I’ll never forget: suitcases rolling across the hallway floor.

Not the small overnight bag she usually took.

The big ones.

The kind you pack when you’re not coming back anytime soon.

I found her in the kitchen dressed like she was heading to a resort, full makeup at 7:00 a.m., lips glossy, hair perfect. Nolan sat at the table eating cereal, still half asleep, eleven years old and unaware his summer was about to turn into a survival course.

Mom didn’t even look at me when she explained.

Boyd had invited her to spend the summer at his cabin in British Columbia. Two weeks, maybe three. She’d be back before I knew it. It would be fine.

I was “an adult now,” wasn’t I?

I had just graduated.

I could handle things.

Then she put **$30** on the counter.

Thirty dollars and one bottle of water.

I still don’t know what the water bottle was about. Maybe she thought it was funny. Maybe she thought it was symbolic. Maybe she grabbed it from the fridge as an afterthought.

But there it was—sitting next to two tens and two fives like we were contestants on a twisted game show where the only prize was not starving.

Nolan looked at me with those big eyes of his. Eleven, still soft around the edges, still believing adults came back when they said they would. I could see him doing the math in his head—the same math I was doing.

Thirty dollars. Two people. An entire summer.

I tried to argue. I tried to explain rent was due in ten days, that we barely had food, that Nolan needed supplies for summer activities, that you can’t leave two kids alone with grocery money and call it parenting.

Mom checked her phone. Smiled at whatever message Boyd had just sent.

She told me I was being dramatic.

She told me to get a job if I needed money.

She told me this was her chance at happiness and I should be supportive instead of selfish.

Selfish.

She actually called me selfish.

The taxi honked outside.

Mom grabbed her bags, kissed Nolan on the head without really looking at him, and said she’d call when she landed.

Then she was gone.

The door shut. The house went quiet.

Nolan didn’t cry right away. He just stared at the **$30** like he was trying to make it multiply through sheer willpower. I wished I had that superpower. I wished I had any superpower at all.

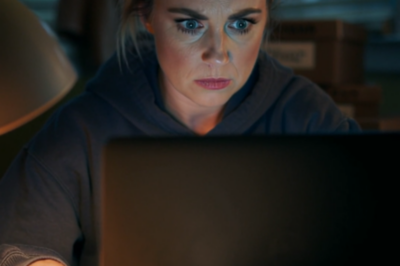

That first night, after Nolan fell asleep on the couch, I sat at the kitchen table and counted the money again like it might change if I stared hard enough.

$30.

The fridge had half a carton of eggs, questionable leftover pasta, condiments, and a whole lot of empty space.

The rent—**$850**—was due July 13.

The electricity bill sat unopened on the counter, fat and smug.

I tried calling Mom around 9:00. Straight to voicemail.

I left a message asking her to call me back, forcing my voice to stay calm while my stomach tightened into a knot.

She didn’t call that night.

Or the next morning.

Or the morning after that.

By day three, I understood something that didn’t fit in my mouth: she wasn’t going to.

Some people have savings accounts for emergencies. Some people have family they can call. Some people have safety nets.

We had $30, an empty water bottle, and each other.

I looked at my little brother sleeping on the couch, still in yesterday’s clothes because I’d been too exhausted to remind him to change. He trusted me. He believed I’d figure it out.

He had no idea I was eighteen and absolutely terrified.

But here’s the thing about terror: it can crush you, or it can light a fire so hot you don’t have time to feel anything except forward.

And I had an eleven-year-old counting on me.

So I made a decision.

I was going to survive this summer. I was going to keep a roof over our heads and food in our stomachs.

And when my mother finally came back from her romantic vacation, she was going to see exactly what her children were capable of.

She just had no idea what that would actually look like.

Here’s the first truth that hit me like cold water: when adults fail you, you either disappear with them—or you build anyway.

Day four started with me staring into our pantry like it might magically refill itself overnight.

Spoiler: it didn’t.

We had peanut butter, half a loaf of bread going stale, generic pasta, and exactly one can of tomato sauce.

I did the math. Small portions, maybe two days. Maybe.

I made Nolan a peanut butter sandwich for breakfast and tried to sell it as a “special summer adventure.”

He didn’t believe me. The kid was eleven, not stupid.

But he ate it without complaining, and somehow that broke my heart more than if he’d yelled.

By day five, the $30 was gone. I spent the last of it on milk, bread, and a bag of rice—because rice feels infinite when everything else is ending.

My grandmother used to say rice was the great equalizer. Rich or poor, everyone eats rice.

She also used to say hard work always pays off.

I was starting to have doubts about that one.

I started looking for work immediately. You’d think summer jobs would be everywhere in July.

Wrong.

Every fast-food place, retail store, and business within walking distance had already hired back in May. The grocery manager actually laughed when I asked if they were hiring—not meanly, more like “honey, where were you two months ago?”

It still stung.

So I got creative.

My first job was cleaning out Mrs. Delgado’s garage three houses down. When I knocked and offered to do it for $20, she looked at me like I’d offered her a winning lottery ticket.

Eight hours later, I had $20, a sunburn, and the knowledge that Mrs. Delgado had kept every single newspaper since 1987.

I didn’t ask why.

Some questions don’t need answers.

Day seven brought a new problem: a bright orange notice taped to our front door.

Mr. Kowalsski—our landlord—was not a patient man. Thick Polish accent, mustache that bristled like it had its own opinions.

The notice gave us seven days to pay rent or face eviction proceedings.

Seven days. $850.

I had $20 and a sunburn.

I called my mother twelve times that week.

Each call went to voicemail.

By the eighth call, her voicemail box was full.

By the tenth, I realized I’d been blocked.

My own mother blocked my number while I was trying to tell her her children might end up homeless.

I tried not to think about what that meant.

Thinking didn’t pay rent. Action did.

A car wash on Henderson Avenue was hiring day laborers. Cash at the end of each shift. No experience necessary.

I showed up at 6:00 a.m. and didn’t leave until 7:00 p.m. The pay was $65 for the week.

I learned things about the inside of strangers’ cars I never wanted to know.

There was a French fry in one minivan that I’m pretty sure was old enough to vote. Another car had so much dog hair I sneezed for three hours straight.

I kept showing up anyway. Scrubbing, smiling at customers who looked right through me like I was part of the hose.

Meanwhile Nolan was supposed to start summer camp. The deposit was $40.

We didn’t have it.

He told me it was fine, that he didn’t really want to go.

But I heard him crying in his room that night.

One of the neighborhood kids made fun of him for wearing the same shorts three days in a row. Called him poor. Called him dirty.

My little brother had done nothing wrong except exist in a story my mother refused to read.

I wanted to find that kid and give him a piece of my mind.

Instead, I went to my closet and pulled out my prom dress.

Pale blue. Floor-length. The nicest thing I’d ever owned. I saved for six months to buy it, and for one night I felt like a princess instead of a backup parent.

The consignment shop gave me $35.

I told myself it was just a dress. That it didn’t matter.

But walking out of that shop, I felt like I’d sold a piece of the girl I used to be—like the summer was turning me into someone harder whether I wanted it to or not.

Day nine brought mail from the electric company: payment overdue. Service interruption in 14 days.

I added it to the pile of things I couldn’t afford to think about.

By day ten, our refrigerator held nothing but condiments—ketchup, mustard, a jar of pickles, and something in a container I was too scared to open.

Nolan made a joke about having a “condiment feast,” and I laughed even though I wanted to cry. That kid had resilience in his bones.

He didn’t get it from our mother.

That night I sat in the shower with the water running and cried until I had nothing left. I couldn’t let Nolan see me break. I was supposed to be the strong one.

I was also eighteen. Exhausted. Broke. Alone.

Mr. Kowalsski came by again. Three days left, he said. Three days to pay or start packing.

He wasn’t cruel about it. I could tell he felt bad. But business was business; he had bills too.

Mrs. Pritchard from next door watched the whole conversation from her porch without even pretending to mind her own business. That woman knew everyone’s secrets and shared them like they were coupons.

By morning, half the neighborhood would know the Harrison kids were about to be evicted.

I walked that night to clear my head, wandering with no destination—just moving so I didn’t collapse.

That’s when I passed Martinelli’s Italian restaurant right as they were closing.

A busboy hauled trash bags to the dumpster out back, and something made me stop.

The bags weren’t full of garbage.

They were full of food.

Bread. Pasta. Vegetables. Containers of sauce. Perfectly edible, thrown away because restaurants can’t sell day-old items and policy doesn’t care if someone is hungry.

I stood there watching bag after bag disappear into the dumpster.

And something shifted inside me.

Not hope yet—hope is expensive when you’re starving.

But the beginning of an idea.

And that idea was about to change everything.

I approached the busboy before I could talk myself out of it.

He was young, maybe my age, tired eyes, marinara stains on his apron. I asked, straight out, “Is that food still good?”

He shrugged. “Yeah, most of it’s fine. They just can’t serve it tomorrow. Health code, liability, policy. Every night it’s like this.”

My stomach growled loud enough to embarrass me.

He looked at me for a long moment, then glanced back at the restaurant door.

Without a word, he handed me two bags.

I thanked him probably fifteen times. He nodded once and went back inside.

I practically ran home.

When I spread everything out on our kitchen table, Nolan’s eyes went wide—fresh bread, pasta that just needed reheating, vegetables with a few soft spots, containers of soup and sauce.

It was more food than we’d seen in days.

Nolan ate until his stomach hurt. I had to make him slow down because I was afraid he’d make himself sick.

That night we went to bed with full bellies for the first time in over a week.

But one meal doesn’t solve a summer.

So my brain started working on something bigger.

The next morning I walked to the public library because our internet had been shut off three days earlier. Apparently you have to pay bills to keep services.

Revolutionary concept.

I spent hours researching food waste, food rescue, food recovery programs—things I’d never heard of before.

Restaurants throw away millions of pounds of perfectly good food every year. Not because it’s spoiled, but because of policy, liability, and the simple fact that they make too much.

There were legitimate organizations that collected extra food and distributed it safely. All it took was structure—proper agreements, guidelines, and liability waivers.

I printed out everything I could find: sample waivers, food safety checklists, examples from other cities.

My stack of papers was thick and messy, but it felt like possibility.

The problem was I was an eighteen-year-old nobody.

Why would any restaurant listen to me?

That’s when I found Mr. Okonquo.

Leonard Okonquo ran the community center on Maple Street. Retired high school teacher, seventy-two, voice like warm coffee, handshake like he could crush walnuts. Everyone knew him.

More importantly, everyone trusted him.

I walked into the community center on day twelve with my stack of papers and a speech I’d rehearsed seventeen times in the mirror.

I told him everything—Mom leaving, the $30, the food waste, the bags from Martinelli’s, my idea to collect extra food and share it with people who needed it.

He listened without interrupting. When I finished, he leaned back and studied me like I was a math problem he intended to solve correctly.

Then he smiled.

“You’ve got a good heart,” he said. “And a messy plan.”

I swallowed. “I know.”

He nodded toward my papers. “Success is like my mother’s stew. You need patience, the right ingredients, and you keep stirring or everything burns.”

Then he pointed at the part that mattered.

“If you want restaurants to trust you,” he said, “you need structure. You need paperwork that looks official. You need a system for pickup and distribution. You can’t just show up with a shopping bag and good intentions.”

So we worked together.

He helped me refine my waiver. The one I found online was okay, but Mr. Okonquo knew how to make it sound legitimate. He taught me how to approach business owners, how to present myself as capable even when I felt like a kid playing dress-up.

He let me use the community center as a base of operations and promised any food I collected could be distributed there.

By day thirteen, I had a plan.

I also had three days until eviction and exactly $43 to my name.

I went back to Martinelli’s, but this time I didn’t sneak around back like a raccoon with hope.

I walked through the front entrance during the afternoon lull and asked to speak to the owner.

Mrs. Martinelli was in her sixties, silver hair in a tight bun, eyes that had seen everything and were impressed by nothing. Thirty-one years running that restaurant will do that.

I handed her my proposal—handwritten on notebook paper because printing costs money.

I explained my idea. Showed the waiver. Told her about the community center, about families nearby who could use the food her restaurant threw away every night.

She stared at my paper for a long time. Then she looked at me.

“How old are you?” she asked.

“Eighteen.”

“Where are your parents?”

I hesitated, then told the truth.

“My mother left me with $30 two weeks ago and hasn’t come back. I’m trying to keep myself and my little brother alive.”

Something shifted in her face—not pity exactly. More like recognition, like she remembered being young and desperate and doing what it took.

“One week,” she said. “Trial. One complaint and we’re done.”

I thanked her so many times she told me to stop before I thanked the words right out of myself.

I left that restaurant feeling lighter than I had in weeks.

That same afternoon, Mr. Kowalsski showed up, and I braced for the final notice.

Instead he stood on our porch looking at me like I was a puzzle.

He’d heard what I was doing—Mrs. Pritchard’s gossip machine was useful for once.

His mustache did that twitching thing it always did.

Then he said he’d give us thirty more days.

“Not charity,” he clarified quickly, as if kindness embarrassed him. “I respect hard workers. My parents came here with nothing. I recognize that.”

Thirty days wasn’t a solution.

But time is everything when you’re trying to build a lifeboat while already in the water.

That night Nolan asked, quietly, if things were going to be okay.

I looked at my little brother—brave, exhausted, never blaming me even when life was cruel.

I said, “Yeah. We’re going to be okay.”

And for the first time since Mom left, I actually believed it.

Because once you see a way forward, fear doesn’t disappear—it just stops driving.

Part 2

The first official night of what I started calling our food rescue operation happened on day fourteen.

I showed up at Martinelli’s back door at exactly 10:00 p.m. with borrowed coolers from Mr. Okonquo and nerves so sharp my hands shook.

The busboy—Thomas, I learned—already had everything ready like we were running a real system and not two exhausted teenagers trying to outsmart hunger.

Three bags of bread, two containers of pasta, vegetables cleaned and sorted, and a tray of lasagna that hadn’t sold.

I loaded the coolers like I was handling treasure.

Because to us, it was.

The next morning I set up at the community center at 7:00 a.m.

Mr. Okonquo spread the word through his network—retired teachers, church friends, neighbors he’d known for decades.

By 8:00 there was a line.

Elderly folks on fixed incomes. Single mothers with kids clinging to their arms. A veteran in a wheelchair who said he hadn’t had a hot meal in three days.

I handed out food until there was nothing left.

And something happened that I wasn’t prepared for.

People thanked me—real gratitude, the kind that makes your throat close because you don’t feel worthy of it.

A woman named Mrs. Patterson grabbed my hands and said, “You’re an angel.”

I wasn’t.

I was just a desperate teenager who had stumbled into something bigger than herself.

By the end of the first week, word spread beyond Mr. Okonquo’s network. People I didn’t recognize showed up, and the need was bigger than my supply.

So I expanded.

Golden Dragon Buffet became partner number two. The owner was skeptical, and I could tell he was worried about liability. But when I showed him the waiver—now properly typed thanks to the library’s free computer access—he nodded slowly.

“Buffet waste is worse,” he explained in careful English. “Food can’t sit. Rules. Every night, enough for thirty.”

“Not anymore,” I said, and my voice surprised me with how sure it sounded.

Sunrise Bakery came next. The owner, a cheerful woman named Patricia Holloway, actually cried when I explained what we were doing.

“My grandmother grew up during the Depression,” she said. “Throwing away bread always felt wrong. I just didn’t know there was another option.”

Nolan became my right-hand man.

He called himself our CFO—Chief Food Organizer—like we were a Fortune 500 company instead of a scrappy little operation built out of borrowed coolers and stubbornness.

He made himself a name tag out of cardboard and marker and wore it like a badge of honor.

Every afternoon he helped sort donations, organize the distribution schedule, and track inventory with the seriousness of someone who understood what scarcity feels like.

By day twenty-five, we had six restaurant partners and were feeding over forty families a week.

The community center became a hub. Volunteers started showing up—people who wanted to help, people who had been helped and wanted to give back.

Mr. Okonquo coordinated everything with the calm efficiency of a man who’d spent thirty years managing teenagers and knew exactly when to be gentle and when to be firm.

Even Mrs. Pritchard—gossip queen, porch sentinel—stopped spreading rumors and started volunteering. I didn’t fully trust her yet.

But she showed up every morning to help sort bread.

People can surprise you.

Then came day thirty.

I was in the middle of organizing a delivery when my phone buzzed with a text from an unknown number.

Except it wasn’t unknown.

It was my mother’s new Canadian number.

The message was brief and brutal:

Having an amazing time. Boyd proposed. Wedding in September. Don’t bother me with drama.

That was it.

No “How are you?” No “Do you have food?” No “Is Nolan okay?” No apology for disappearing.

Just an announcement and an instruction not to inconvenience her happiness.

Nolan saw my face and asked what was wrong.

I showed him the text.

He read it twice, handed my phone back, and didn’t say a word.

But I saw something in his eyes that hadn’t been there before—not sadness.

Something harder.

Like the last little piece of him that still hoped Mom would come back and make it right finally crumbled away.

We didn’t talk about it. There was work to do.

Day thirty-three brought a new challenge.

A woman in a blazer walked into the community center holding a clipboard and an expression that meant she’d been trained to keep her feelings out of her face.

“I’m Dorothy Reeves,” she said. “County health department. I have questions.”

Someone filed an anonymous complaint: that I was distributing food without proper permits or approvals.

My heart sank so hard I felt it in my knees.

Dorothy wasn’t unkind. She could see what we were doing was good.

But rules were rules.

If I wanted to continue, I needed permits, a certified kitchen, official nonprofit status.

Cost: roughly **$500** in fees, plus finding a commercial kitchen.

She gave me two weeks.

Two weeks to find $500 when I could barely keep the lights on at home.

Two weeks to make everything official while I was still technically just a kid trying not to drown.

I held it together until Dorothy left.

Then I sat on the community center steps and tried very hard not to panic.

Mr. Okonquo found me twenty minutes later and sat down beside me, his old knees creaking.

When I told him everything, he was quiet for a long moment.

Then he said, “Obstacles are opportunities wearing ugly masks.”

I let out a laugh that sounded more like a sob. “That’s… poetic.”

“It’s practical,” he replied. “Every successful person hits a wall. The ones who succeed find a door.”

I didn’t have $500.

But I had something else.

I had a story.

The next day, I called the local newspaper.

Jasmine Torres—young reporter, hungry for stories that mattered—came to the community center like I’d offered her a match in a windstorm.

She interviewed me, Nolan, Mr. Okonquo, volunteers, families.

The article ran the following week with the headline: Teen turns tragedy into triumph. Local food rescue feeds dozens.

The response hit like a wave.

Donations started pouring in—$5, $20, $100 from anonymous envelopes.

Within a week, we had over $2,000.

Enough for permits, fees, and everything we needed.

But more than money, we had attention.

People shared the article on social media. Local businesses reached out to partner. Someone from the mayor’s office called to “express support.”

Someone suggested we needed an official name.

Nolan wanted Food Avengers. I vetoed it on the spot, because I didn’t need a superhero lawsuit on top of everything else.

We settled on Second Chance Kitchen.

Because that’s what we were giving people.

And that’s what life, in a twisted way, was giving me.

What I didn’t know was the article reached farther than our little town.

It reached all the way to Canada.

And it set something in motion that would bring everything to a head.

Here’s the hinge no one warns you about: once your story is public, the people who hurt you can’t hide behind private excuses anymore.

Part 3

The TV interview happened on day forty-four.

Channel 7 picked up the story from the newspaper article, and suddenly I was sitting in a real studio under lights so bright they made your skin feel like it was being interrogated.

A makeup artist tried to cover the dark circles under my eyes.

She needed a lot of concealer.

“I haven’t slept properly in forty-four days,” I told her, half-joking.

She didn’t laugh. She just added more powder and wished me luck like she understood luck had nothing to do with it.

The anchor, Rebecca Stanton, had done her homework. She didn’t just ask about Second Chance Kitchen. She asked how it started.

And I hadn’t planned to tell the whole truth.

I prepared vague answers—“difficult circumstances,” “family challenges”—because you learn early that telling the truth about a parent makes people uncomfortable. They want clean stories. They want villains to be strangers.

But then I thought about Nolan watching at home. I thought about the families we served who had their own stories, their own silent humiliations.

I thought about how silence protects the people who hurt you.

So I told the truth.

All of it.

I said my mother left for Canada on July 3 with her boyfriend.

I said she gave us **$30** and a bottle of water for the entire summer.

I said she blocked my calls and sent one text in six weeks—not to check on us, but to announce an engagement.

I said everything we built came from desperation, not inspiration.

Rebecca’s face shifted as I spoke. I saw the crew exchange glances behind the cameras.

This wasn’t the fluffy segment they expected.

This was raw.

That evening the segment aired with a new headline: Abandoned teen creates food rescue operation while mother vacations in Canada.

By morning it went viral.

Not just locally—nationally.

My phone exploded with messages, interview requests, strangers sending support from everywhere. Second Chance Kitchen received more donations in twenty-four hours than we’d gotten in the entire month before.

A local business owner, Mr. Fitzgerald, who ran a catering company, offered us free use of his commercial kitchen.

Permit applications were fast-tracked by the county.

We became an official nonprofit with tax-exempt status.

Twelve restaurants became partners. Then more.

We were feeding over eighty families a week.

Volunteers signed up faster than we could train them.

And the story reached Canada.

My mother called on day forty-six.

I almost didn’t answer.

But something made me pick up—maybe curiosity, maybe the part of me that still wanted to believe she’d say, “Are you okay?”

She was furious.

Not apologetic. Not concerned.

Furious.

“How could you embarrass me like this?” she demanded, her voice shaking with rage. “Boyd’s family saw it. His business partners saw it. Everyone is asking questions!”

I listened for almost five minutes without saying a word.

When she finally paused for breath, I said one thing.

“You left us with $30 for nearly two months.”

She sputtered about me being dramatic. Exaggerating. Not understanding adult relationships.

Then she announced she was coming home immediately to “fix this mess” and “set the record straight.”

She hung up before I could respond.

I should have felt scared.

Instead I felt something closer to peace.

Let her come.

Let her see what we built.

Let her meet the truth she’d been outrunning.

What I didn’t know—what I couldn’t have known—was that the news story had caught the attention of more than just my mother.

Mrs. Pritchard had been carrying a secret for weeks.

Back when she was still the neighborhood busybody, she was the one who filed the anonymous complaint with the health department.

Skeptical of what we were doing. Worried about health risks. Maybe jealous of the attention.

But watching me work—watching Nolan show up every day like a little man trying to hold the world together—did something to her.

Guilt, maybe.

Or maybe she finally recognized the line between “gossip” and “danger.”

Three weeks before the news story aired, Mrs. Pritchard called Child Protective Services.

Not to hurt me.

To help.

She reported that an eleven-year-old had been left without a guardian for over a month. She provided dates, details, everything she’d observed.

CPS opened an investigation.

They couldn’t do much while my mother was in Canada, out of jurisdiction.

But they watched. They waited. They built a case.

When the news story confirmed everything—dates, the absence, the location—CPS coordinated with local police.

Day forty-seven: the day my mother’s plane landed.

I was home with Nolan when we heard cars pull up.

Multiple cars.

I looked out the window and saw two police cruisers and an unmarked sedan parked in front of our house.

My first thought was I’d messed up something with Second Chance Kitchen. A permit issue. A new complaint. A detail I’d overlooked.

I told Nolan to stay inside and walked out to meet them.

The officer in charge was tall with kind eyes. His name was Sergeant Morrison.

“Are you Kristen Harrison?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Is your mother expected home today?”

“Yes. Any minute.”

He explained why they were there: child abandonment, neglect of a minor, failure to provide adequate care for a dependent.

Serious charges.

They needed to speak with my mother as soon as she arrived.

I stood on the porch processing the fact that my mother was about to face official questions for what she’d done—not because I reported her, but because someone else saw the truth and refused to stay silent.

Twenty minutes later, a taxi pulled up.

My mother stepped out looking like she’d just left a resort—tanned, relaxed, designer sunglasses perched on her head. She had two new suitcases, expensive ones, probably gifts from Boyd.

She was already assembling her expression of righteous anger, ready to storm in and regain control.

Then she saw the police cars.

Her steps slowed.

Anger turned to confusion, confusion to fear.

She looked at the officers, then at me, then back at the officers.

Sergeant Morrison approached and explained calmly.

I watched my mother’s face cycle through shock, denial, outrage, panic—like she was flipping through emotional channels trying to find one that worked.

She tried to argue. Tried to spin. Tried to make her “vacation” sound reasonable.

Then she made the mistake of looking past the officers—past me—toward the community center two blocks away.

A banner hung above the entrance: SECOND CHANCE KITCHEN — SERVING OUR COMMUNITY.

Beneath it was a photo of me and Nolan smiling.

My mother stared at that banner for a long, silent moment.

Then she looked at me. Really looked at me, maybe for the first time in years.

I wasn’t the scared eighteen-year-old she left behind.

Nolan stepped onto the porch beside me, shoulders back, not hiding, not crying—standing like someone who had learned his own worth.

We weren’t broken. We weren’t desperate. We weren’t the mess she expected to return to.

We were survivors.

We were thriving.

And she had missed all of it.

Her mouth opened.

No sound came out.

Her designer luggage sat forgotten in the street.

The officers asked her to come with them to answer questions.

She went.

What choice did she have?

As the police car drove away with my mother in the back seat, I didn’t feel triumph.

I felt peace.

Whatever happened next, we had already won.

Part 4

The investigation took three weeks.

Child Protective Services interviewed me and Nolan. They interviewed neighbors, Mr. Okonquo, volunteers, even Mrs. Martinelli. They documented everything: the **$30**, the blocked phone calls, the single text about an engagement, the **47 days** of absence.

My mother hired a lawyer. Of course she did.

Boyd’s money—because yes, Boyd—covered it.

Then Boyd vanished.

His wealthy family wanted nothing to do with that kind of publicity. The engagement was called off about six hours after the news story aired.

Fairy tales crumble fast when reality shows up uninvited.

In the end, my mother wasn’t arrested. The court considered she had no prior record, and Nolan hadn’t been physically harmed.

She received three years of probation, mandatory parenting classes, and **200 hours** of community service.

And here’s where my story takes a turn most people didn’t see coming.

When the judge asked where she would complete her community service, I made a decision that surprised everyone—including myself.

“I’d like her to do it at Second Chance Kitchen,” I said.

The courtroom went still.

People thought I was crazy.

Mr. Okonquo looked at me with concern. Nolan stared like I’d lost my mind.

Why would I want my mother anywhere near what we built?

But I understood something punishment alone doesn’t teach.

Jail time wouldn’t make her a better person.

Shame wouldn’t fix her.

The only way she would ever understand what she did was if she saw it—lived it—spent two hundred hours surrounded by the community that fed her children when she wouldn’t.

The judge approved it.

My mother’s first day was awkward beyond description.

She showed up in clothes too nice for sorting vegetables, hair styled, expression tight with humiliation and resentment. The volunteers who knew our story gave her looks that could freeze water.

She didn’t speak to anyone.

But community service has a way of wearing down walls.

Week after week she showed up. Sorted bread next to Mrs. Pritchard—the neighbor who had called CPS. Packaged meals next to Mr. Okonquo, who treated her with firm expectations and zero softness for excuses. Served food to families who thanked her without knowing who she was.

Slowly, something shifted.

At first it was small: she stopped styling her hair on service days. She asked questions about how logistics worked. She learned volunteers’ names.

She started arriving early instead of exactly on time.

Then, in week six, she broke.

We were in the back room boxing up meals for delivery, just the two of us and the sound of tape ripping and cardboard folding.

Out of nowhere she started sobbing—ugly, messy sobs, hands over her face like she could block the past from entering.

When she finally caught her breath, she looked at me with red eyes and said the words I’d waited my whole life to hear.

“I’m sorry.”

Not “I’m sorry you feel that way.”

Not “I’m sorry but—”

Just: “I’m sorry.”

She said she spent her whole life looking for someone to take care of her. After my father left, she’d been so desperate to find security again she forgot she was supposed to be the one providing it.

She said she convinced herself we were fine, that I was mature enough to handle things, that her happiness mattered too.

She said she was selfish.

She said she was wrong.

And she didn’t expect forgiveness.

I didn’t forgive her that day.

Forgiveness isn’t a switch. It’s a door you open slowly, checking for traps.

But I told her the door wasn’t locked.

And I meant it.

Here’s the hinge I didn’t expect: watching her finally feel the weight of what she did didn’t heal me—watching myself survive it did.

Part 5

That was six months ago.

Today Second Chance Kitchen operates out of a real commercial kitchen donated by Mr. Fitzgerald. We partner with **23** restaurants across the city. We serve over **200 families** every week. We have four paid staff members and more than forty regular volunteers.

I received a full scholarship to State University for social entrepreneurship. Classes start next fall.

Nolan is thriving. He wrote an essay about our summer that won a county-wide writing competition. The kid has a future in storytelling, which makes sense—he lived one.

And my mother?

She completed her 200 hours months ago.

She still volunteers twice a week.

She’s not perfect. We’re not the kind of family you see in commercials, laughing over breakfast like nothing happened. Some wounds take longer.

But she’s trying—really trying.

She started therapy. She got a steady job. She stopped looking for a man to rescue her and started learning how to rescue herself.

Last week she asked if she could take Nolan to a movie. Just the two of them.

He said yes.

Progress comes in small steps.

I still have that water bottle, by the way—the one she left us with on July 3rd.

It’s empty now, scratched and cheap and ridiculous, and I keep it on my desk where I can see it every day.

Not out of bitterness.

As a reminder.

A reminder that sometimes the people who should lift you up are the ones who leave you down.

A reminder that rock bottom isn’t the end of the story—it’s the foundation you build on.

A reminder that **$30** and an empty bottle can become something extraordinary if you refuse to give up.

When my mother came home, she saw police cars and a banner and a daughter she didn’t recognize.

But what made her go silent wasn’t the trouble she was in.

It was realizing we didn’t need her anymore.

That we built something beautiful out of the nothing she left behind.

That her absence gave us the one thing she never could—the chance to discover who we really were.

Some lessons cost more than others.

Some lessons are worth every penny.

News

s – I Helped An Old Man On The Bus — My Sister Turned WHITE The Moment She Saw Him Because I…

I Helped An Old Man On The Bus — My Sister Turned WHITE The Moment She Saw Him Because I……

s – I Fed Homeless Boys in My Café in 1997 — 21 Years Later They Showed Up the Day I Was…

I Fed Homeless Boys in My Café in 1997 — 21 Years Later They Showed Up the Day I Was……

s – My Husband Divorced Me, Taking Even CUSTODY — He Had No Idea What He Would Face and…

My Husband Divorced Me, Taking Even CUSTODY — He Had No Idea What He Would Face and… The first thing…

s – I Walked In On My Husband And My Daughter’s Best Friend — But What Broke Me Most Was Her Smile

I Walked In On My Husband And My Daughter’s Best Friend — But What Broke Me Most Was Her Smile…

s – He gripped my hand: “Only 3 days! Finally everything’s mine.” After that smile, I made one call…

He gripped my hand: “Only 3 days! Finally everything’s mine.” After that smile, I made one call… The little {US…

s – Years later I came back and saw my twin sister covered in bruises in her own home…

Years later I came back and saw my twin sister covered in bruises in her own home… The TSA agent…

End of content

No more pages to load