Transgender Inmate Girl Infected Warden With 𝐇𝐈𝐕 After Secret Affair And Was 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝 | HO”

Prologue: A Relationship That Should Never Have Happened

When Leon Brooks walked through the steel-framed staff entrance of Cumberland Correctional Institution each morning, he moved with the reflexive calm of a man who had long ago mastered the rhythm of prison life. Twenty years as a corrections professional had taught him when to speak, when to stay silent, and how to maintain the fragile order that keeps a carceral system functioning.

It also taught him the first rule of survival:

Never cross the line with an inmate.

But one winter morning, a newly processed prisoner named Zara Hendris—a 24-year-old transgender woman with an attentive gaze and a quiet sense of self-possession—arrived inside Seablock. From that moment forward, the line that once defined Leon’s professional life began to blur, then fade, and finally vanish.

The relationship that followed remained hidden from nearly everyone behind those walls. It evolved through guarded conversations, stolen moments, and a mutual sense of emotional need that neither fully understood until it was too late.

By the time the affair collapsed, one person would be dead, another imprisoned, a family destroyed, and an entire correctional system under scrutiny.

This is the story of how that happened—reconstructed through investigative interviews, internal memoranda, forensic findings, and eyewitness accounts from inside the prison.

pasted

Chapter One: The New Arrival

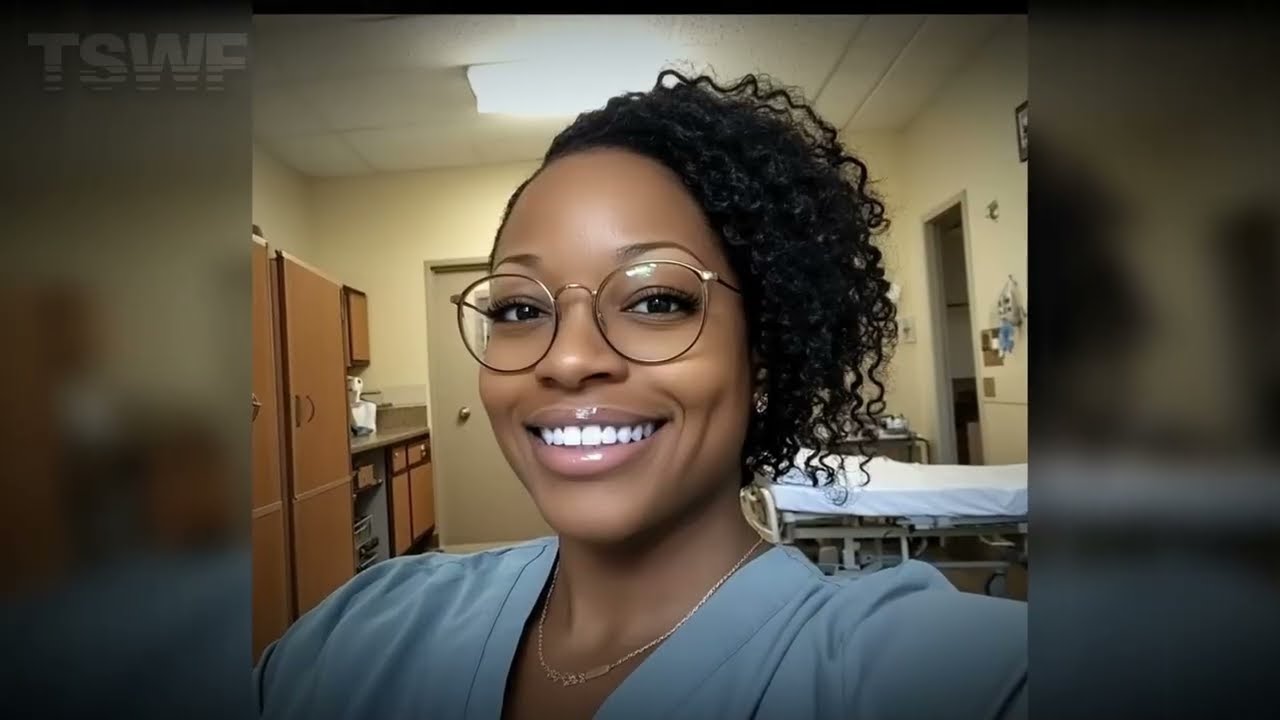

On paper, Hendris arrived at Cumberland with an unexceptional record—minor offenses, no history of serious violence, and a medical file flagged for sensitive handling. She was quiet. Observant. Polite. And, according to multiple witnesses, instantly noticeable.

Brooks first saw her during early-morning rounds—alone on the bunk, reading. That is rare in prison. Most inmates sleep, talk, or simply stare out at the world beyond their bars. Books require concentration. They invite reflection. They resist the emotional numbness that helps time pass.

“First night. Can’t sleep,” she told him through the cell window.

Brooks filed the interaction into the mental ledger every seasoned warden keeps. She was vulnerable. She would need protection. And she would need watching—not just because of policy, but because transgender inmates disproportionately face harassment and violence in U.S. correctional settings.

At first, he insisted to himself that his interest was purely professional.

But soon the patrols outside Cell 23 became longer. The conversations deepened. Boundaries softened.

And the man who once lived by rules began to break them quietly.

pasted

Chapter Two: Two Lives Converge

A Warden With Something to Lose

At home, Leon Brooks had a wife, a mortgage, two children, and a reputation built over decades. Inside the prison, he had seniority, trust, and authority.

Budget cuts soon changed that calculus.

The prison administration announced staff reductions. Even veteran officers could lose their jobs over a single infraction. The message was unmistakable:

Do nothing—ever—that can be questioned.

Yet as those pressures mounted, Zara—isolated, intelligent, navigating gendered hostility inside the facility—kept seeking him out in conversation. And he kept responding.

She sensed his strain. He sensed her loneliness.

In prisons, connection can feel like oxygen. And oxygen is addictive.

Chapter Three: The Secret, and the Silence

The Diagnosis No One Was Supposed to Know

Zara had been living with HIV, medically stable on antiretroviral therapy. Her doctor confirmed her viral load remained controlled. But stigma inside prisons is acute. She feared exposure. She feared retaliation. She feared losing what little agency she had left.

So she kept the diagnosis private.

And—critically—she kept it private even as her relationship with Brooks blurred into an emotional intimacy that neither acknowledged publicly, yet both understood.

Her private notebook, later obtained by investigators, reflected growing anxiety:

“Things are getting too serious.

Leon has feelings.

What happens when he finds out the truth about me?”

Inside confinement, truths do not remain buried forever.

Chapter Four: Discovery—and Collapse

Brooks said he discovered the diagnosis by accident, recognizing the medication when he saw Zara taking it.

He confronted her.

She did not deny it.

In his first interview with detectives, Brooks recalled shock giving way to anger. He feared for his health. He feared for his family. He feared the collapse of everything he had built.

Days later, medical tests confirmed what he dreaded:

He was now HIV-positive.

The moment became the hinge on which the rest of the tragedy turned.

What followed was a private spiral—a man already under institutional pressure experiencing fear, betrayal, guilt, and self-hatred.

Investigators would later conclude that those emotional pressures converged in the early-morning hours of the 27th.

Chapter Five: The Night in Cell 23

The scene, at first glance, resembled a suicide.

A rope. Torn sheets. A stool overturned on the floor.

But Detective Irvin Murphy, a veteran of homicide work, noticed the details first:

• The stool was too far from the body.

• The knot was wrong-sided for a left-handed person.

• The wrists bore faint compression marks, as if bound briefly then released.

These were not the marks of surrender.

They were the signs of staging.

Cameras captured a warden-uniformed figure near the cell around 3:20 a.m.—after Brooks’s shift should have ended. The build, height, and timing matched him.

Under questioning, his story cracked.

He admitted being there.

He admitted confronting Zara.

He admitted the affair.

He admitted the diagnosis.

And then, after retaining counsel, he admitted the rest:

He strangled her during a confrontation fueled by rage, fear, and panic—then staged the death to look self-inflicted.

His recorded confession aligned with forensic findings down to the smallest detail.

The case, though devastating, became clear.

pasted

Chapter Six: Fallout

Families—and Systems—Break

Brooks was arrested at home in front of his wife and children. He pled guilty under a negotiated plea and received 15 years in prison, with parole off the table for a decade.

His wife filed for divorce. His children withdrew from him completely.

The Department of Corrections launched an audit, uncovering structural failures in oversight, boundaries, and staff-inmate interaction protocols.

The prison warden resigned.

Several staff members were disciplined.

And the broader system was forced to confront longstanding vulnerabilities:

• Lack of protective structures for LGBTQ+ inmates

• Lack of mental-health support for correctional staff

• Insufficient monitoring of boundary-violating contact

• Deep stigma surrounding HIV in correctional environments

Zara was buried quietly.

Her family declined to claim her remains.

A small group of activists attended.

No one who loved her spoke publicly.

No one won.

pasted

Chapter Seven: What Remains

Detective Murphy closed the file with little satisfaction. The story—once reduced to rumors about “forbidden sex and disease”—was far more human and far more tragic.

A transgender woman, already vulnerable, carried a medical burden that society still weaponizes against her community.

A veteran officer—emotionally exhausted, unsupported, and already at risk—allowed a line he had once sworn to uphold to disappear.

A system with weak safeguards let two people collapse into each other in ways that were always going to end badly.

And a death behind bars became one more reminder that prisons magnify every human weakness—and every institutional failure.

Epilogue: Lessons, If Anyone Is Listening

The narrative of blame alone is too easy here.

This case demands more difficult questions:

• How are transgender inmates protected—or not—from isolation, abuse, and neglect?

• How do prisons monitor the boundary-crossing risk that can grow quietly and invisibly between staff and inmates?

• How do we remove HIV stigma so diagnosis is disclosure-safe rather than secrecy-driven?

• And how do we care for correctional officers, who face psychological strain most civilians will never understand?

Because if none of those questions are answered, what happened inside Cell 23 becomes less an anomaly than a warning.

And warnings ignored rarely stay isolated for long.

Chapter Eight: The Detective Who Refused the Easy Answer

Detective Irvin Murphy never liked simple explanations. His supervisors nicknamed him “the accountant” because he treated cases like ledgers—every claim had to balance with evidence. Suicide cases, in his experience, often invited closure. They were tragedies that ended themselves.

This one did not balance.

Standing in Cell 23, Murphy kept returning to the details. The rope fiber. The placement of the stool. The angle of the knot. The faint marks around the wrists. The absence of defensive wounds that normally accompany self-harm by hanging. And the timeline—the narrow window of unmonitored time when only staff with keys and authority could have entered.

Every small contradiction mattered.

So did the statements. Indira Cole, the cellmate, held steady through multiple interviews. Zara had been making plans. She was reading, writing, preparing to take classes after release. There were no signals of withdrawal. No coded farewells. No sudden giving away of belongings—indicators officers are trained to watch.

Murphy wrote a single sentence in his notebook:

“Someone needed this to look like suicide.”

He would spend the next days proving whether that someone was Leon Brooks.

pasted

Chapter Nine: What the Cameras Saw—and Didn’t

Cumberland’s security system was a patchwork of aging cameras, partial blind spots, and outdated storage hardware. Some hallways had views from multiple angles. Others had none.

But the hallway outside Cell 23 did have coverage.

Murphy and the facility’s IT coordinator sat together in the control room, jogging frame-by-frame through the grainy black-and-white feed from the night of the 27th. Most of the footage was unremarkable: a night warden passing at the top of the hour, the dull stillness of sleeping inmates, the steady rhythm of institutional quiet.

Then—3:20 a.m.—movement.

A correctional officer entered the frame. Height similar to Brooks. Build similar to Brooks. Uniform standard issue. The camera could not capture the face—lighting and angles left it in shadow—but the gait was distinctive.

The officer paused outside Cell 23. Five minutes. Eight. Then left.

There was no log entry explaining the visit.

No reported disturbance.

No reason for anyone to be at that door at that hour.

Murphy didn’t declare certainty—but certainty was no longer required. He had now crossed from possibility into probability.

pasted

Chapter Ten: The Diary

The call from the property inventory clerk came late afternoon.

“We’ve found something,” she told him.

Inside Zara’s small nightstand drawer was a notebook, its cover worn from handling. The entries were neat and reflective. They spoke of routine frustrations, interpersonal dynamics, and the exhaustion of incarceration. But as Murphy read deeper, the tone changed.

Zara wrote about a warden who spoke to her like a person, who lingered at the bars and asked about books, who seemed lonely in a way she recognized.

She never used his name.

She didn’t need to.

The final entries read like emotional confession—affection, confusion, fear. And one unresolved tension ran through the pages:

She had not told him about her HIV diagnosis.

Murphy paused. This was the missing link—the concealed truth, the psychological detonator. It did not justify violence. It did not excuse rage. But it explained the emotional temperature in the days leading to her death.

The notebook also revealed something else:

Zara did not want to die.

Her handwriting spoke of longing—not surrender.

pasted

Chapter Eleven: The Second Interview

Murphy requested a second formal interview with Leon Brooks.

The veteran officer arrived subdued, his confidence drained. His hands trembled faintly on the table. He kept asking for water. His lawyer sat beside him, advising restraint.

Murphy began carefully.

“Mr. Brooks, I want you to reconsider your earlier statement.”

He placed photocopied pages of Zara’s diary on the table. The words about emotional connection. About worry. About the undisclosed diagnosis.

Brooks’s expression shifted. The mask slipped.

His first instinct was denial.

Then deflection.

Then silence.

When Murphy revealed the HIV diagnosis—and the confirmation of Brooks’s positive test result—the older man broke. Anger flashed. Then tears. Then the resigned tone of a man who realizes truth can no longer be outrun.

He admitted the relationship had become intimate emotionally, though he insisted the physical boundary was rarely crossed. Investigators later concluded there was more physical intimacy than he admitted—but not less.

He admitted he was terrified when he saw the medication. Admitted he confronted her. Admitted he blamed her.

He stopped at the edge of the final confession.

His lawyer asked for a recess.

pasted

Chapter Twelve: The Ethics of Silence

In the days after the confession, Murphy spoke with Dr. Samuel King, the prison’s medical director. King was calm, methodical—a physician accustomed to treating vulnerable populations under secrecy and stigma.

He summarized the key facts:

• Zara had been diagnosed three years earlier.

• She was compliant with treatment, with suppressed viral load.

• Her condition did not make her dangerous to others in daily contact.

The doctor also confirmed she had the legal right to privacy unless a situation presented imminent harm.

But secrecy within a closed system is combustible.

Murphy found himself confronted with uncomfortable questions:

Where does a person’s right to medical privacy end?

Where does another person’s right to informed consent begin?

And when those rights collide behind bars—who protects whom?

Policy offered only partial answers.

Life offered none.

pasted

Chapter Thirteen: What Happened at 3:20 a.m.

The final version of events came from Brooks himself, under counsel, during a recorded confession. It was clear. It was linear. And it was devastating.

He used his keys to enter after hours. He went directly to Zara’s cell. He woke her. He confronted her. Words escalated—fear, blame, betrayal pouring out unchecked.

She cried.

She apologized.

She tried to explain.

He admitted he lost control.

He strangled her.

And then, in a frantic attempt to erase the crime, he staged the scene to mimic suicide—binding her wrists temporarily to obscure finger-mark bruising, tying a sheet rope, and placing the stool as prop.

He said he loved her.

He said he regretted everything.

He said he would carry what he had done for the rest of his life.

Murphy believed the remorse.

But remorse did not change the facts.

pasted

Chapter Fourteen: Courtroom Without Drama

The District Attorney’s office faced a choice—pursue a full murder trial, or enter a structured plea. Prosecutors weighed the confession, the forensic evidence, the motive, and the profound trauma suffered by multiple parties—including Brooks’s family.

The plea agreement included:

• Acknowledgement of responsibility

• A murder conviction with mitigating factors

• A 15-year sentence, parole restricted for at least 10

In court, Brooks appeared thin, haunted. He did not contest the charges. He did not ask for sympathy. He did not attempt to minimize his actions.

He listened as the judge described a betrayal of public trust, a devastating failure of ethics, and an irreversible harm.

Then he was led away in handcuffs—now an inmate in the same system he once supervised.

No family members sat behind him.

The silence inside the courtroom carried more force than any outburst could have.

pasted

Chapter Fifteen: A System on Trial

The state Department of Corrections quietly launched an administrative review.

The audit did not stop at Brooks.

It examined:

• Oversight gaps that allowed boundary-violating relationships

• Camera blind spots and outdated monitoring

• Staff mental-health support deficiencies

• Lack of trauma-informed training for handling LGBTQ+ inmates

• Procedural weaknesses in confidentiality and safety protocols

The report found system failure layered atop human failure.

The warden resigned.

Supervisors were disciplined.

Policy reforms followed, including:

• Mandatory ethics and boundary-awareness training

• Independent reporting channels for inmates

• Stronger screening for officer emotional fatigue

• Updates to surveillance coverage

• Clarified guidelines around HIV privacy and education

None of it restored a life.

But it made the next tragedy less likely—and sometimes in institutional reform, that is the only achievable outcome.

pasted

Chapter Sixteen: The Survivors

The Family Left Behind

Brooks’s wife filed for divorce.

His children changed schools.

Neighbors avoided eye contact.

The household became quieter, then empty.

They had not committed a crime, yet they paid a price the legal system could not quantify.

The Cellmate

Indira Cole was granted early parole for cooperation with investigators. She moved out of state. Friends say she still avoids discussing what happened inside Cell 23.

The Staff

Some carried guilt. Others resentment. Most carried exhaustion.

Correctional culture does not always encourage vulnerability—but the case forced many to confront the emotional risk they face daily.

The Community

LGBTQ+ advocates cited Zara’s case as a warning about vulnerability and stigma inside carceral environments—where identity, safety, and privacy collide under constant watch.

pasted

Chapter Seventeen: The Questions That Remain

The case file now rests in storage.

But the questions do not.

Would things have ended differently if…

• …Brooks had received adequate emotional-health support?

• …the facility had better oversight systems?

• …Zara had been able to disclose safely?

• …HIV stigma did not carry such weight?

• …the prison had stronger safeguards preventing staff-inmate intimacy?

There are no certain answers.

Only patterns.

Patterns that repeat wherever systems remain under-resourced, under-trained, and structurally strained.

PART 3 — Systems Under Pressure

Chapter Eighteen: When Justice Avoids a Trial

When the District Attorney’s office accepted a plea deal rather than a full trial, the decision raised questions in legal circles familiar with custodial-death prosecutions.

Trials serve public functions. They surface evidence. They assign accountability. They allow communities to witness justice being done. But they also carry risks—unpredictable juries, retraumatization of witnesses, and exposure of institutional weaknesses that governments are sometimes reluctant to spotlight in open court.

Behind closed doors, prosecutors weighed:

• A detailed, recorded confession

• Strong forensic corroboration

• The emotional devastation to multiple families

• The public cost of a lengthy trial

• The vulnerability of the deceased and the risk of stigmatization in open testimony

A plea guaranteed accountability without spectacle.

It also avoided what legal scholars call “secondary victimization”—when courtroom narratives retraumatize the deceased through invasive scrutiny into their identity, medical status, and personal life.

For Zara Hendris, that mattered.

Her name was already becoming a lightning rod in circles predisposed to misunderstand her story.

A trial would have amplified that.

So justice in this case arrived quietly, clinically, and with finality—fifteen years, parole eligibility restricted, conviction entered.

The courtroom emptied.

The file advanced from “open” to “closed.”

But for those who study power dynamics in carceral environments, the case was just beginning to matter.

Chapter Nineteen: The Psychology of Boundary Collapse

Experts in correctional mental health often describe “institutional drift”—a slow erosion of professional boundaries in closed environments.

It rarely begins with misconduct.

It begins with conversation.

A door check that lasts a minute longer.

A human moment in a place designed to crush them.

A compliment.

A piece of personal disclosure.

A sense that someone “finally sees me.”

Inmates can become emotionally dependent.

So can staff.

And the risk increases sharply when two conditions converge:

1. Staff emotional strain

Correctional work is psychologically corrosive. Studies consistently associate it with:

• burnout

• depression

• hypervigilance

• strained marriages

• substance misuse

• elevated suicide risk

Staff are trained to appear strong. They are rarely trained to process vulnerability.

2. Inmate vulnerability

Transgender inmates face some of the highest rates of harassment and assault in custody. That isolation can magnify emotional need and heighten attachment to any staff member who treats them with consistent dignity.

Together, those dynamics can create gravitational pull.

What begins as care slides into familiarity.

Familiarity slides into dependency.

Dependency slides into secrecy.

And secrecy—inside a prison—is the most dangerous ingredient of all.

In interviews, colleagues described Leon Brooks as “steady,” “professional,” and “tired.” He wasn’t a predator. He wasn’t a caricature of corruption.

He was human.

That, ironically, was part of the danger.

Because human beings—unlike policies—can break.

Chapter Twenty: HIV, Stigma, and Fear

Medical records show Zara’s HIV status was medically controlled, meaning she was on treatment and managing her condition responsibly. Modern science is clear:

When HIV is successfully suppressed, transmission risk is extremely low to nonexistent.

But science alone does not erase fear.

Inside prison systems, where rumor spreads faster than policy memos, HIV stigma still operates as social currency—sometimes weaponized, often misunderstood.

Zara’s decision to maintain privacy was legally protected.

Brooks’s shock at discovering the diagnosis was emotionally real.

The tragedy lived in the space between law, science, and fear—a space where panic can become detonator.

Experts later emphasized:

“The issue was not HIV itself—it was secrecy, stigma, and the emotional collapse of a boundary that never should have eroded in the first place.”

Had either the relationship or the stigma been prevented, this homicide likely never occurs.

Both went unaddressed.

Chapter Twenty-One: The Ethics That Failed

The prison audit concluded that three ethical pillars collapsed sequentially:

Pillar One: Institutional Duty of Care

The facility had a legal and moral duty to ensure safe custody for vulnerable inmates—especially those at heightened risk of exploitation or harm.

Zara was doubly vulnerable:

• transgender identity

• concealed medical status

Yet she was monitored only for behavioral compliance, not well-being.

Pillar Two: Professional Boundaries

Staff-inmate relationships require distance not because inmates are undeserving of kindness—but because power imbalance makes true consent impossible.

Any personal intimacy is, by definition, coercive—no matter how mutual it feels.

The system failed to reinforce that truth.

Pillar Three: Internal Accountability

Blind spots in surveillance and culture allowed private emotional entanglement to grow undetected.

And so when crisis came at 3:20 a.m., no one was there to intervene.

Because no one knew what needed to be stopped.

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Hidden Cost of Working in Prisons

While the narrative often focuses on inmate risk, correctional officers also operate inside chronic psychological hazard zones.

Researchers estimate:

• PTSD rates among correctional workers rival combat veterans

• Suicide risk significantly exceeds the national average

• Burnout develops rapidly in mid-career officers

Yet mental health support for staff remains limited, stigmatized, or underfunded.

Former colleagues described Brooks as a man carrying:

• economic anxiety during budget cuts

• emotional exhaustion

• a long-untreated sense of professional loneliness

The system held him responsible, as it had to.

But the tragedy also forced administrators to confront a second truth:

Unwell officers make unsafe prisons.

Chapter Twenty-Three: The Cellmate Who Watched It Happen Slowly

Indira Cole, Zara’s cellmate, was never physically present during the killing. But she watched the relationship unfold.

She saw the conversations linger.

She saw the glances.

She saw the hesitation in both.

Prisons operate as constant theaters of observation. Very little remains hidden.

Yet inmates rarely report boundary-erosion—not out of apathy, but because whistleblowing can isolate them, endanger them, or erase what little protection they have.

Cole later said:

“Zara thought he was different. That he saw her.

But the rules are there for a reason.

Without them, nobody is safe.”

Her early parole relocated her far from Cumberland.

But memories travel.

And some prisons never leave you.

Chapter Twenty-Four: The Warden Who Walked Away

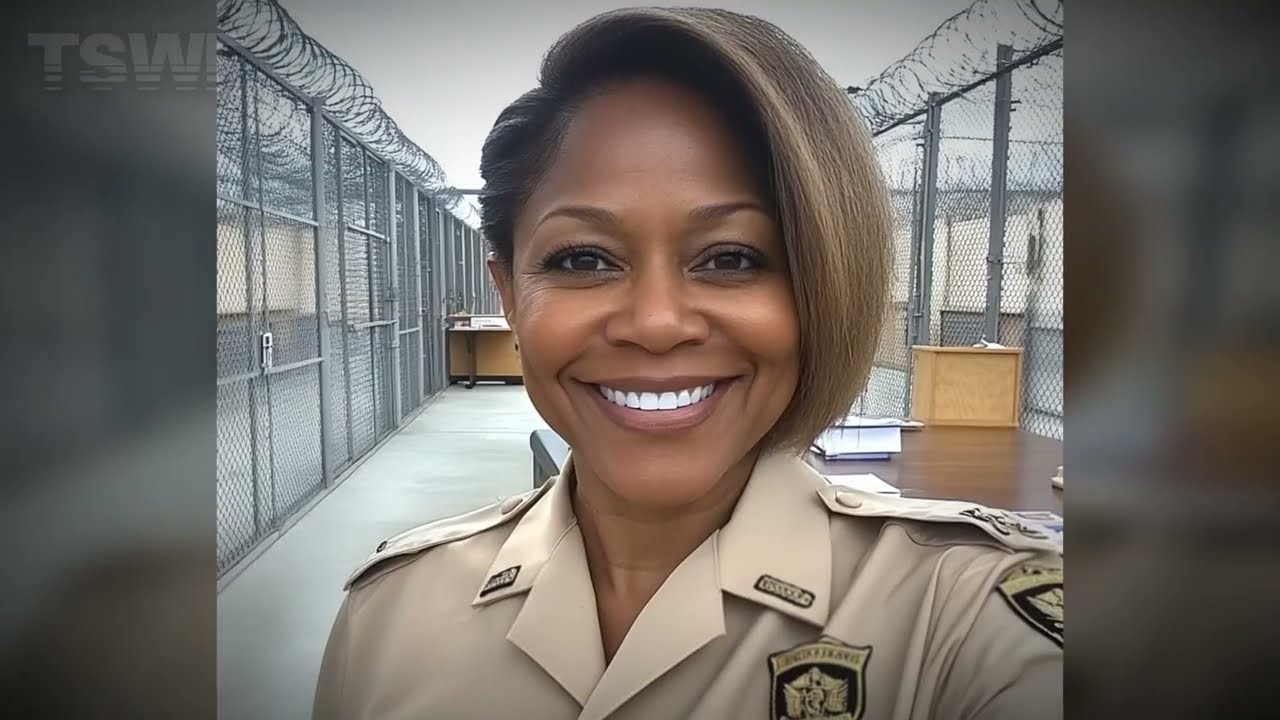

Warden Selena Wright had spent years navigating shrinking budgets, overcrowding, and political scrutiny. She did not commit violence. She did not encourage misconduct.

But she also did not prevent it.

Her resignation, submitted weeks after the audit, reflected a truth many administrators privately share:

Systems absorb blame unevenly.

Sometimes leadership steps aside because staying means becoming the story.

Sometimes they step aside because the weight becomes unmanageable.

Either way, the departure marked a symbolic end to an era in Cumberland.

Chapter Twenty-Five: Media, Myth, and the Narrative Battle

As the story circulated beyond the county, it risked mutating into myth:

• A “forbidden romance story.”

• A “disease narrative.”

• A “crime-of-passion thriller.”

But those narratives flatten reality.

This case was not romance.

It was not morality play.

It was not sensational entertainment.

It was structural vulnerability meeting human frailty in a sealed environment.

The investigation—patient, methodical—kept returning to one anchor:

Zara Hendris was a person under state custody.

The state owed her safety.

She did not receive it.

And when that duty fails, the outcome is never simply “personal.”

It is institutional.

It is systemic.

It is preventable.

Chapter Twenty-Six: Life Behind the Sentence

Inside his new facility—now a prisoner rather than staff—Leon Brooks works in the library. His behavior is compliant. He avoids conflict. He is reported to read often and speak little.

He receives no letters from his children.

He does not contest the silence.

Those who have interviewed him describe a man living inside permanent reckoning—less angry now, more emptied, aware that every day is the echo of an irreversible act.

He remains HIV-positive, now receiving the same kind of care he once supervised others receiving.

The irony is not lost on him.

Nor on anyone else.

Chapter Twenty-Seven: The Unanswered What-Ifs

In the aftermath, investigators, advocates, and policy analysts all returned to the same unanswered questions:

What if…

• A supervisor noticed the lingering conversations?

• Confidential reporting channels for boundary violations existed?

• Staff emotional-support programs were normalized rather than stigmatized?

• Correctional policy embraced trauma-informed care for transgender inmates?

• Public education had already dismantled the fear that still surrounds HIV?

Would Zara still be alive?

Would Brooks still be free?

Would a family still be whole?

No one can say with certainty.

But nearly everyone agrees:

This tragedy did not begin at 3:20 a.m.

It began long before—with each unchecked erosion of boundary, each unrecognized cry for support, each failure to intervene while intervention was still painless.

PART 4 — Aftermath and Reckoning

Chapter Thirty-Eight: The Weight of a Closed File

Case files do not feel regret.

When the folder containing State vs. Leon Brooks slid into the archive shelf, the criminal justice system considered its work complete. The chain of custody was sealed. The evidence catalog was stamped. The confession transcript was indexed. The autopsy photographs were stored in a climate-controlled vault.

Officially, justice had been delivered.

Unofficially, a series of unanswered questions lingered like residue.

Detective Irvin Murphy understood this instinctively. He had worked too many cases to believe that closure begins when paperwork ends. He went back to routine assignments. He opened new case notebooks. He returned to the familiar rhythm of slow questions and slower answers.

But occasionally, when he passed the corrections complex on his commute, he would glance toward the perimeter fencing and think of a young woman’s last night—and a veteran officer’s final, irreversible mistake.

There was no satisfaction in that memory.

Only responsibility.

Chapter Thirty-Nine: A Grave Few Visit

At the city cemetery, the section reserved for indigent or unclaimed burials sits apart from the more elaborate headstones. Grass grows unevenly. Flowers arrive rarely. Time does not.

Zara Hendris was laid to rest there.

A small group stood at the burial: an attorney, a few community advocates, and one silent guard who remained in the distance and never gave his name. No relatives spoke. No choir sang. No formal obituary described her life before incarceration.

Yet even in that quiet corner, she became more than a file number.

Her name entered policy discussions. Her circumstances entered training academies. Her vulnerability entered the administrative conscience of institutions not accustomed to confronting emotion.

She was finally seen.

Not in the way she deserved.

But seen nonetheless.

Chapter Forty: A Family That Never Asked for This

At the Brooks residence, curtains remained drawn for weeks after the arrest. The neighborhood children whispered. Newspaper carriers handled the walkway with unnecessary solemnity. The bicycles on the porch rusted in place.

Patrice Brooks, now a single mother overnight, spent her days alternating between legal meetings, workplace leave paperwork, and managing the emotional fallout inside her home. Her children struggled to understand how the man who made pancakes on Saturdays could now be wearing a prisoner’s uniform several counties away.

They were not responsible for his actions.

But they were not protected from their consequences.

In many ways, they became the second-order victims the criminal justice system cannot measure. Broken routines. Broken trust. A surname that now carried association instead of identity.

The court docket did not include their pain.

That does not mean it did not exist.

Chapter Forty-One: A System That Was Forced to Look in the Mirror

In state capital conference rooms and correctional leadership training centers, PowerPoint slides began appearing with cautious titles such as:

“Boundary Awareness: Lessons from Cumberland.”

“Vulnerability Management in Custody.”

“Confidentiality, Risk, and Human Factors.”

The Cumberland case became a teaching instrument—not to sensationalize tragedy, but to prevent repetition.

The reforms were incremental but meaningful:

• Ethics & Boundary training shifted from policy recitation to scenario-based learning.

• Supervisory monitoring tools flagged early signs of over-familiarity.

• Anonymous inmate reporting channels were strengthened and insulated from retaliation risk.

• Surveillance coverage gaps were narrowed.

• HIV education modules emphasized fact, not fear.

• Transgender inmate support protocols expanded beyond classification and into lived safety.

• Officer mental-health access became confidential, proactive, and destigmatized.

No single policy solved every risk.

But systems learn best from the cases that hurt the most.

And this one hurt.

Chapter Forty-Two: The Man on the Inside

Inside his new facility, Inmate Brooks followed a quiet routine. Library duty. Meals. Head counts. Medical monitoring. Compliance without resistance.

He did not request special treatment.

He did not grant media interviews.

He rarely used the phone.

Staff described him as respectful but withdrawn, a man occupying his sentence rather than serving it. The irony of now being under the authority he once exercised did not escape him.

He read frequently.

He complied with treatment.

He did not contest the silence from his children.

In a letter that never left the prison mailroom because he chose not to send it, he reportedly wrote a single line to his family:

“I made a wound that time cannot close.”

The law had already spoken.

Conscience spoke longer.

Chapter Forty-Three: The Lessons Experts Won’t Let Fade

Criminal justice reform advocates and corrections administrators distilled the Cumberland tragedy into five enduring lessons:

Lesson One — Vulnerability Requires Active Protection

Transgender inmates and others at elevated risk do not need symbolic recognition.

They need operational safeguards that anticipate risk rather than reacting to it.

Lesson Two — Confidentiality and Education Must Coexist

HIV stigma is often more dangerous than HIV itself in controlled environments.

Confidentiality must be preserved.

Education must be universal.

Fear must be replaced with fact.

Lesson Three — Boundaries Are Not Optional

Staff-inmate emotional boundaries are not merely ethical guidelines.

They are safety systems.

When they collapse, power imbalance turns intimacy into coercion and secrecy into risk.

Lesson Four — Correctional Staff Are Human

Ignoring the psychological toll of correctional work does not make it disappear.

It makes it detonate later.

Support must be accessible, confidential, and stigma-free.

Lesson Five — Accountability Is an Institutional Duty

Accountability is not about punishment alone.

It is about alignment—ensuring that authority, training, policy, and humanity point in the same direction.

Chapter Forty-Four: The Story That Refuses Simplification

Attempts to reduce the Cumberland case into a headline have always failed.

It is not simply:

• a scandal

• a romance

• a crime of passion

• a medical story

It is a collision of structural weakness and human frailty inside a sealed environment.

A transgender woman sought dignity.

A correctional officer sought meaning.

A system failed to recognize risk forming in plain sight.

And a preventable death followed.

The file may be closed.

The lesson is not.

Chapter Forty-Five: A Final Reflection

In the end, every prison story asks a question about responsibility.

Not only who committed the act—but who might have prevented it.

This case does not argue that systems can eliminate human failure.

It argues that systems must never stop preparing for it.

Because behind every numbered door, every uniform, every badge, every inmate jumpsuit—

there are people.

And when policy forgets that truth,

tragedy becomes procedural.

News

Ethan finally felt chosen—until a Sunday dinner flipped everything. His new wife went pale when his brother walked in… because she used to be married to him, before she transitioned. “It wasn’t the revelation that turned deadly, but Ethan’s fear of always being “second,” and pride did the rest.” | HO

The 29-year-old husband discovered that his new wife was his brother’s transgender ex-wife, so he… When someone builds a new…

She Was Live-Streaming Her Fight with Her Mother-in-Law — Minutes Later, Her Husband 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐭 Her | HO

She Was Live-Streaming Her Fight with Her Mother-in-Law — Minutes Later, Her Husband 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐭 Her | HO Margaret Elaine Cole,…

Married 24 years, they came on a game show for laughs—until she hesitated at one question: “Would you still marry him?” He walked offstage. Everyone thought it was the end. Twist: he came back, got on one knee, and handed her a medical school application—“No more choosing love over your dream.” | HO!!!!

Married 24 years, they came on a game show for laughs—until she hesitated at one question: “Would you still marry…

He bragged online about his “upgrade” and the diamond ring, convinced he’d outgrown his quiet ex. While he planned the wedding, she quietly stepped into a billionaire inheritance—and bought the company behind his venue. AND his reception got shut down mid-toast… by his ex’s “welcome to new ownership” call. | HO!!!!

He bragged online about his “upgrade” and the diamond ring, convinced he’d outgrown his quiet ex. While he planned the…

He Walked In On his Fiancee 𝐇𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐒*𝐱 With Her Bestie 24 HRS to Their Wedding-He Gets 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐭 𝟏𝟑 𝐓𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐬 | HO!!!!

He came home early—24 hours before the wedding—and found his fiancée in bed with her “best friend.” He didn’t yell….

Steve Harvey STOPS the Show — Husband’s MISTRESS Was in the Audience the Whole Time | HO!!!!

Family Feud looked normal—until Steve noticed one woman in a red dress staring a little too hard at the stage….

End of content

No more pages to load