The Kentucky Barn 𝐌𝐮𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬: 𝟏𝟎 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐤𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐁𝐮𝐫𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐀𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐞 After Damaging Tobacco Crops | HO”

It was just past dawn. The padlock was twisted off. The door hung wide. Inside: ropes cut, leaves scattered, a third of the crop stomped, torn, and ruined. Fresh footprints in the dust. Not animals. Not teenagers. Intentional. Personal. Like someone wanted the Barkers to bleed.

Eli walked the rows without speaking, then turned to his brothers and said three words, low and cold.

“This was inside.”

The implication sat heavy. No stranger would risk this. No outsider would know the path through the back holler, past the dead oak and the broken fence line. This was someone sleeping under their roof.

Something old stirred in the Barker men, something handed down like a family Bible: you don’t ruin a man’s field. You don’t spit on the hand that feeds you. And you sure don’t cross a Barker in their own barn.

Not all the workers felt the same to Eli. A few—maybe four—had honest eyes and hard hands. Respectful. Quiet. But others moved like trouble wrapped in denim and sweat. Daryl, with the gold tooth and the loud mouth, always telling stories that didn’t add up. Claimed he’d worked tobacco down in Hardin County but couldn’t name the difference between a primer and a stripper. Marcus, eyes like wet coal, speaking little, watching everything. Eli didn’t like the way Marcus looked at the barn, like he saw more than he should. And Jonah—the youngest—couldn’t have been more than eighteen, skinny as a fence post with a nervous laugh and a stutter when he got excited. Eli felt a flicker of pity for him. The boy tried. That counted for something.

The days started before sunup. The Barkers gave orders—what rows, what barns, how to carry without bruising the leaf. Most listened. A few didn’t. Twice Eli caught Daryl dropping bundles too hard. Once he found a cigarette butt smoldering too close to a curing shed. He didn’t say a word. He just pointed to the barn wall, blackened from a fire back in ’58. That blaze had taken a quarter of their crop and nearly took their grandfather with it. Fire was no joke in a tobacco barn.

The hinge was this: the workers saw barns as buildings, but the Barkers saw barns as vows—and breaking vows had consequences.

By mid-September, tension had a pulse. The vandalism had sent them scrambling to fill quotas. Every leaf mattered, every hour. And still some treated it like a joke—slacking off when backs were turned, gambling in the bunkhouse, sneaking out after dark.

Then Eli found the carving. Scratched into a beam in the upper barn: BARKER with a line through it, and a crude drawing of a noose. He didn’t show his brothers right away. He ran his hand over the mark like it might explain something. That night he gathered the workers and gave them one rule.

“The barns are sacred,” he said. “They feed us, clothe us, keep this farm alive. You treat them with care or you leave.”

No one spoke. Not even Daryl. But Eli caught the glance Marcus shared with Raymond—a big bruiser with a busted nose and arms like fence posts.

Noah wanted to fire the whole crew. Simon wanted to wait, watch, catch them in the act. Eli stared out past the field like his father used to do when something went wrong.

“We’ll handle it our way,” he said.

The line got drawn then, not with law, but with blood—though nobody used that word out loud.

Five days later, the second strike hit harder.

It was a Saturday morning. Eli woke before the rooster, before the dew even settled, with a knot behind his ribs. When he stepped outside, he smelled it—not smoke, not rot, but wet tobacco. Fresh, violated.

He didn’t call for his brothers. They met him halfway down the hill, drawn by the same cold premonition. They walked in silence toward the south field, where the last high-nicotine burley stood waiting to be cut.

Leaves—hundreds—lay shredded in the dirt. Not broken by weather, not dropped from sickness. Slashed and scattered. Posts kicked loose. Ropes sliced. Tarps torn. Simon knelt and studied a cut: straight edge, like a box cutter. Noah picked up a ruined leaf and crumbled it slowly in his palm.

“They knew where to hurt us,” Noah said.

Eli didn’t look at the damage for long. He stared past it—toward the bunkhouse.

They found boot prints in the mud leading from the fence line and back. At least three sets. Someone came under cover of dark and stayed long enough to carve vengeance into the harvest.

By late morning, they salvaged what they could, rushing the rest to curing. The weight in Eli’s chest didn’t ease. It hardened.

After lunch, they walked to the bunkhouse. Ten men lounged inside or leaned on the wall, laughing over a poker table. The laughter died when the Barkers stepped in.

Eli didn’t raise his voice. He looked at each man one by one like he was carving their faces into memory.

“Someone touched what they shouldn’t have,” he said. “Ruined what keeps this place alive. We don’t know who. Not yet. But the man who did it will answer for it. I swear on every bone buried in these hills.”

Marcus met his gaze, cool as pond water. “You got proof?”

“Not yet,” Eli said.

Raymond leaned forward, elbows on knees. “Then maybe you ought to watch where you point your threats.”

Simon took a half step. Noah pressed a hand to his chest, holding him back.

“We ain’t calling the law,” Eli said. “That’s not how this gets handled. You know something? Now’s your time to speak.”

Silence. Jonah opened his mouth, then closed it. The boy looked terrified.

Eli turned, slow and deliberate. “Then we’ll figure it out ourselves.”

That night, the Barkers took turns sitting on the porch with rifles across their laps. A storm rolled in from the west. Thunder came slow and distant, like footsteps behind you that don’t stop. Inside the bunkhouse, three men whispered. One said, “We went too far.” The others said nothing.

The hinge was this: once Eli said “our way,” the farm stopped being a workplace and became a courtroom with no appeal.

The Barkers weren’t violent by nature. They weren’t saints either. But their violence lived buried, like a shotgun behind a barn door—kept for the moment when talking stopped working and rules changed. In the hills of Kentucky, those rules were simple: you don’t steal what’s not yours, you don’t damage a man’s field, and you don’t forget a debt owed.

By Monday, the brothers turned that old code into action. Eli laid out a plan in the barn where his father taught him to tie bundles.

“This ain’t for rage,” Eli said. “This ain’t to feel better. This is to set things right.”

Simon spoke first. “We talking blood?”

Noah looked down. He didn’t have to say yes. His silence meant commitment.

Eli nodded. “Not all of them. Not yet. But someone’s going to talk.”

They tested the group. Cut rations. Switched bunkhouse water to the older well that tasted like rust. Took the radio away. Watched who complained, who muttered when they thought nobody listened. Daryl cracked first, pacing outside, yelling about fairness.

Simon waited until Daryl was alone behind the shed, grabbed him by the collar, pressed him to the wall.

“You ruin our field?” Simon asked.

Daryl shook his head too fast. “I don’t know what you’re talking about, man.”

Simon leaned in. “You ever been in a barn fire, Daryl? Ever heard a man begging when there ain’t nowhere to go?”

Daryl’s eyes went wide. “I didn’t do nothing,” he said. “Swear to God. But I know who did.”

That was enough.

By sunset, the Barkers had a name: Raymond. The one who’d been mouthing off since day one. Daryl said Raymond bragged. Said it would “teach you rednecks a lesson.” Said he slashed stalks, tore tarps, laughed about it because he thought nobody would do anything.

Eli didn’t smile. He just nodded.

That night behind the equipment shed, lantern light threw long shadows. Three rifles leaned against a post.

“We deal with Raymond,” Eli said. “Clean. No mess. No scene.”

Noah asked the question they were all thinking. “What if the others get in the way?”

Eli paused. “Then they go too.”

The next evening, they invited the whole crew to the barn, told them it was time to move cured bundles, said they’d feed them afterward—old mountain hospitality. Ten men walked in. The barn door creaked shut behind them.

The bolt slid home.

The hinge was this: the sound of that barn bolt was quieter than a shout, but it was louder than any verdict that would come later.

Inside, the barn smelled of old wood, dust, and cured leaf. The sweetness had soaked into beams over decades. The ten workers stood clustered near the center, shifting weight, hands in pockets, eyes moving toward the walls like they were already mapping exits.

Eli stood by the door with a lantern. Noah leaned against a post with a rifle slung across his back. Simon stayed near the wall, watchful.

Raymond broke first, trying for casual. “What’s this about? You said we were moving bundles.”

“We are,” Eli said. “Just not the way you thought.”

The door bolt clicked deeper. Several men flinched. Jonah stepped back, breath coming fast.

Raymond’s laugh was sharp and forced. “You can’t lock us in here.”

Eli lifted the lantern, light catching Raymond’s face. “You cut our crop. You treated our work like a joke.”

“You got proof?” Raymond snapped.

Simon moved fast. One hard blow dropped Raymond to the floor. The barn erupted in motion—two men rushed Simon, Noah swung the butt of his rifle to keep them back, another worker lunged toward the door and found Eli in his path.

“No one leaves,” Eli said, voice steady. “Not yet.”

Daryl dropped to his knees, hands up. “I told you who it was. I told you everything.”

“That don’t change what happened,” Eli replied.

Jonah slid down against a post, whispering prayers so fast the words tangled.

Raymond tried to push up, face wet, eyes furious. “You’re dead for this,” he spat. “The sheriff’s gonna—”

Simon shoved him back down. “Ain’t no sheriff in here.”

It didn’t last long. It wasn’t about a fight. It was about control.

When the movement settled, Eli walked to the wall and picked up a kerosene can.

The smell cut through the tobacco sweetness instantly, sharp and undeniable. Men started yelling. One rushed Eli and Noah drove him down. Someone sobbed. Someone shouted they didn’t do anything.

Eli twisted the cap. “One last time,” he said. “Who helped him?”

No one spoke.

Eli poured in a slow line along the base of the wall. Not wild. Not sloppy. Deliberate. The way you do something when you’ve already decided what it means.

Jonah’s voice broke. “I didn’t do nothing. I just needed work.”

Eli stopped pouring and looked at him. For a second something flickered—hesitation, maybe. Then it hardened.

“You stayed,” Eli said. “That’s enough.”

Simon struck a match.

The flame was small—almost harmless—until it wasn’t. The fire moved fast in a barn built for dry leaf. Smoke thickened. Panic swallowed space. The door did not give.

Outside, the brothers moved away from the structure as the roof began to glow. The night sky turned the color of warning. By the time the barn collapsed into itself, the Barkers were already down the hill.

By dawn, there was nothing left but a blackened frame and a smoking ruin.

The hinge was this: the barn that once held the Barker family’s future became, in one night, the place that destroyed it forever.

When the sheriff arrived, it was already too late. Eli met him at the gate, hat in hand, face drawn.

“Faulty lantern,” Eli said. “Barn caught. Men were inside.”

The sheriff looked past him at the wreckage. “Door was secured.”

Eli didn’t flinch. “We secure it every night. Animals.”

The sheriff stared a long moment. “Fire marshal’ll want to look.”

“Of course,” Eli said.

By noon, the county buzzed. Ten men gone. A tragedy, they called it. A terrible accident. People said barns burn fast. Tobacco burns faster. It was easier to believe in accident than in the alternative, because the alternative would mean admitting the hills could still produce something darker than poverty.

But some things don’t burn clean.

Harold Whitaker, the county fire marshal, walked the site without speaking, studying scorch patterns and the warped lock recovered from ash. He didn’t like what the fire was telling him. The burn intensity was wrong. The origin looked guided.

“This burned hotter than a lantern accident,” he said.

The sheriff shifted. “Tobacco burns hot.”

“It does,” Whitaker said, “but fire leaves signatures.”

He asked for state review.

That night, the Barker house went quiet in a new way. No supper. No prayer. Simon sat on the back steps staring into dark. Noah paced the yard until he wore paths into dirt. Eli sat at the kitchen table with a mug he didn’t drink from.

The next day, widows arrived. Not all ten had family close, but some did. Margaret Ellis, whose husband Walter had taken the job for quick money, stood at the edge of the ruins and didn’t cry. She held something folded in her pocket and stared like she was trying to see a moment she’d missed.

Whitaker returned with equipment and a second investigator. They sifted ash, took samples, mapped the burn. Kerosene residue showed in places it shouldn’t have. The door hardware told its own story.

The sheriff began to feel the ground shift under him. He’d grown up with the Barkers. He’d hunted with their father. The idea of them crossing this line didn’t fit the picture he’d carried in his head for decades.

He drove out before sunset and told Eli, “They’re saying it wasn’t an accident.”

Eli nodded once. “They always say that when they don’t understand the land.”

The sheriff studied him. “You telling me straight?”

“I told you what happened,” Eli said.

The sheriff left without another word.

That night, Margaret Ellis went home and opened the last letter her husband sent before the fire. It wasn’t long. It didn’t accuse. It worried. It said the Barkers were watching them. Said something bad was coming. Said if anything happened, it wouldn’t be an accident.

The next morning, she drove to the sheriff’s office and handed him the paper that survived what her husband didn’t.

The hinge was this: the state didn’t start believing in murder because of rumor—it started believing because a folded letter refused to burn.

Margaret’s letter changed everything. It was only a few paragraphs in careful print, but it carried the kind of fear you don’t fake. The sheriff read it three times, each pass heavier, then called Frankfurt again. Within twenty-four hours, Whitaker returned with a full state team.

They dug deeper. Dirt samples from beneath the barn floor. Chemical residue from beams that hadn’t fully collapsed. Splinters sealed into bags and labeled. Kerosene. Not lantern fuel. Not accident.

The bolt that had held the door shut was examined under magnification. Heat distortion warped it, but it never failed. The fire’s origin point and spread pattern didn’t match a toppled lantern. It matched poured accelerant.

Whitaker requested access to Barker property. He brought the sheriff with him. Eli met them on the porch, arms crossed, stone-faced. Simon and Noah stood behind him like shadows.

Whitaker spoke carefully. “Mr. Barker, what you told us about the lantern and the door—it doesn’t match what we’re seeing.”

Eli’s eyes didn’t move. “You think I did it.”

“I think,” Whitaker said slowly, “something happened here that goes beyond accident.”

Eli’s voice stayed even. “I told you everything I know.”

Whitaker nodded. “Then we keep looking.”

No search warrant that day. No arrest. But something shifted anyway. In town, whispers became full conversations. At the diner, voices lowered when the Barker name came up. At church, hands hesitated before shaking. Respect turned brittle.

At the Barker table that night, nobody ate much. Martha cleared plates without comment. She didn’t ask questions. She didn’t need to. She’d lived on that land long enough to know what silence meant.

When the kids were asleep and the moon threw long shadows across the porch, Martha looked at Eli and said only, “They’ll come.”

Eli nodded. “I know.”

The state team built the case in layers: fire science, physical evidence, the letter, interviews with worker families who described fear in the days before. A deputy mapped movements during the final week. Who left the bunkhouse late. Who tried to quit. The thread tightened.

Meanwhile, the Barkers tried to keep living. The co-op still expected weight. The contract still mattered. The market still didn’t care about tragedy. Eli pushed the farm forward by force of will, pulling old bundles from storage, repacking what remained, doing whatever it took to meet the numbers. The check arrived. It kept the mortgage afloat. Martha watched Eli fold it and put it away without a smile.

“Was it worth it?” she asked.

Eli didn’t answer.

Not because he didn’t have an answer.

Because saying it out loud would make it real.

The hinge was this: the money arrived like it always did, but the barn bolt had already become a witness that couldn’t be paid off.

The arrests came under fog. State troopers turned onto Barker land with headlights cutting through gray like knives. No sirens. No theatrics. Just a warrant and the weight of what the state now believed.

Eli was awake on the porch, coat on, hat in his lap. Simon and Noah waited inside until the knock came. Martha stood in the doorway, hands folded, face unreadable.

The lead trooper spoke calmly. “Eli Barker, we have a warrant.”

Eli stood without hesitation. “I figured you would.”

The charges were read: arson, murder, ten counts.

Eli didn’t argue. He turned, placed his hands behind his back, and waited for cuffs. Simon went quiet. Noah hesitated long enough to look back at the house, then stepped forward.

In town, a neighbor stood at the edge of the road, barely visible through the fog, and removed his hat as they passed. Whether it was respect or farewell, nobody said.

The trial moved to Lexington, far from the ridges, but not far enough to loosen what the Barker name meant. Reporters filled the steps. Family members of the ten workers sat together, faces set in grief that had nowhere to go.

The prosecution laid out the case like a finished puzzle: accelerant patterns, chemical residue, a door secured from outside, the lock and bolt that held. Margaret Ellis read her husband’s letter in court, voice shaking, and the room went still. The defense tried to argue uncertainty, claimed accident, claimed panic, claimed misinterpretation of burn patterns. But the science didn’t bend.

When the fire marshal testified, he spoke in numbers and diagrams, not emotion. The jury watched and understood. One story fit the evidence. The other did not.

The verdict came back: guilty. All three brothers. All counts.

During sentencing, the judge asked if Eli had anything to say. He stood slowly and looked not at the judge, but at the families behind the rail. His voice was gravel.

“You ruin a man’s field,” Eli said, “you ruin his family. That has to matter.”

He paused, eyes dropping to his hands. “But maybe I stopped being a man the night I stopped believing there was another way.”

The judge sentenced the brothers to life without parole.

No cheers. No applause. Just a silence so heavy it felt like weather.

The hinge was this: the Barkers believed they were protecting 200 acres of legacy, but the law measured their protection as ten lives taken.

The state separated them in prison—Eli to central Kentucky, Noah east, Simon south—officially for security, but everyone knew the real reason. Keep them apart. Dismantle the unit that had held so tight.

Eli became an inmate number, wore beige, worked quiet jobs, read his Bible before dawn. He spoke little. Guards respected his silence. Inmates left him alone. There was something in his eyes that discouraged conversation—less rage than a grief that never found a place to go.

Simon worked laundry. He shrank that first year. He stopped speaking for months, then started again in short sentences. He wrote his mother letters that always ended the same way: I didn’t mean for it to happen like that.

Noah struggled most. Suicide watch twice. Refused visitors. Hands shook. A cough that echoed down concrete. The youngest wasn’t built for consequence.

Back in Laurel County, Barker land went dormant. No planting that spring. Fields grew wild. The house stood dark. The porch light went off for good. Martha moved closer to her sister in town. She kept Eli’s jacket folded in a drawer and didn’t speak his name after sentencing.

Anna Barker died two winters later. The obituary was short. No mention of the trial, no mention of the fire. Just her name, her children, and a Psalm about justice rolling down like waters. At her funeral, Martha stood with chin up, accepting condolences that didn’t linger. The air around the Barker name still burned.

The graves of the ten workers were marked with simple stones. Donations covered the cost. Flowers appeared sometimes—nothing extravagant, just proof someone remembered. Margaret Ellis visited once a year, stood ten minutes in silence, then left. She never remarried. Never moved. Her home stayed quiet, filled with photos and folded letters.

In town, the story faded from headlines but not from memory. Teenagers drove past the old Barker place at night and dared each other to step onto the land. Most didn’t. A few did, and later swore they heard things—wood creaking, the wind catching wrong in the trees, an echo they couldn’t name.

Years later, a developer offered to buy the property, turn it into cabins and trails. Martha declined without hesitation. Once a year she returned, brought a folding chair, and sat near the steps listening to the wind. No tears. No words. Just presence.

The last time she came, she placed a wooden cross where the barn had stood. No inscription. No names. Just a marker, as if to say someone lived here, someone died here, someone chose fire.

Then she left and didn’t come back.

The house will collapse someday. Roof will give. Foundation will crack. The Barker name will fade for most. But the ground will remember. Earth doesn’t forget heat or ash. And when the wind moves just right across those hills, the story returns—not as rumor, not as legend, but as a warning carved into the quiet: some debts don’t disappear when the barn is gone, and some bolts, once slid home, never stop echoing.

News

On Their Wedding, She Caught the Groom Sleeping with Another Man— 5 Minutes Later, He Was Found D3ad | HO”

On Their Wedding, She Caught the Groom Sleeping with Another Man— 5 Minutes Later, He Was Found D3ad | HO”…

Nanny Disappears In Dubai After Revealing She’s Pregnant For Sheikh’s Son — 3 Months Later, She’s… | HO”

Nanny Disappears In Dubai After Revealing She’s Pregnant For Sheikh’s Son — 3 Months Later, She’s… | HO” “I don’t…

Wife Infects Disabled Husband with 𝐇𝐈𝐕 After Affair with Married Lover | HO”

Wife Infects Disabled Husband with 𝐇𝐈𝐕 After Affair with Married Lover | HO” Trauma exposes cracks no one wants to…

Delaware Bride 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝 at Registry by Groom’s Father for What She Did 7 Years Ago | HO”

Delaware Bride 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝 at Registry by Groom’s Father for What She Did 7 Years Ago | HO” “Aaliyah—Aaliyah—look at me,…

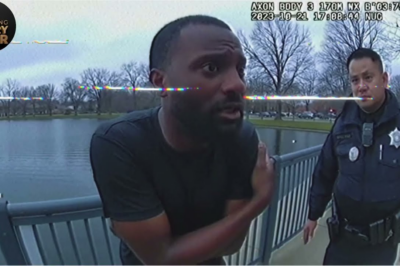

Cop Arrests Black Veteran After He Saves Drowning Child — Purple Heart Hero, $7.8M Lawsuit | HO”

Cop Arrests Black Veteran After He Saves Drowning Child — Purple Heart Hero, $7.8M Lawsuit | HO” He didn’t bring…

Staff Protect Black Female Teacher from Masked ICE Agents Without Warrant — She Wins $11.7M Lawsuit | HO”

Staff Protect Black Female Teacher from Masked ICE Agents Without Warrant — She Wins $11.7M Lawsuit | HO” She was…

End of content

No more pages to load