He Vanished On A Hunting Trip After A $380K Policy, Years Later His Truck Was Found With Another Man | HO”

On the side of a two‑lane Louisiana highway in 1998, a state trooper leaned against his cruiser, sipping lukewarm iced tea from a plastic cup. A small US flag decal peeled slightly at the corner of his windshield, flapping when the night breeze picked up. It was supposed to be another quiet evening on Highway 6—speeders, expired tags, nothing that would end up in a courtroom.

Then a primer‑gray Chevrolet Silverado rolled by with mismatched plates and a paint job that looked like it had been done in someone’s backyard. The trooper flipped on his lights, more out of habit than suspicion. Minutes later, he would be cuffing a man who lied about his name, running a VIN that pinged on a nine‑year‑old missing person report, and staring into the cab of a truck that should have disappeared in 1989.

That stop didn’t just ruin someone’s night. It cracked open the truth behind a “hunting trip” that never happened and a $380,000 policy that turned a quiet union welder into a target. By the time the dust settled, the Silverado itself would end up in evidence storage, one of the last solid things left of a man the law had already tried to forget.

Nine years before that traffic stop—on November 3, 1989—Shreveport, Louisiana, woke up like any other workday. Streetlights blinked off over small brick houses, coffee percolated in cramped kitchens, and shift workers headed out into the dark.

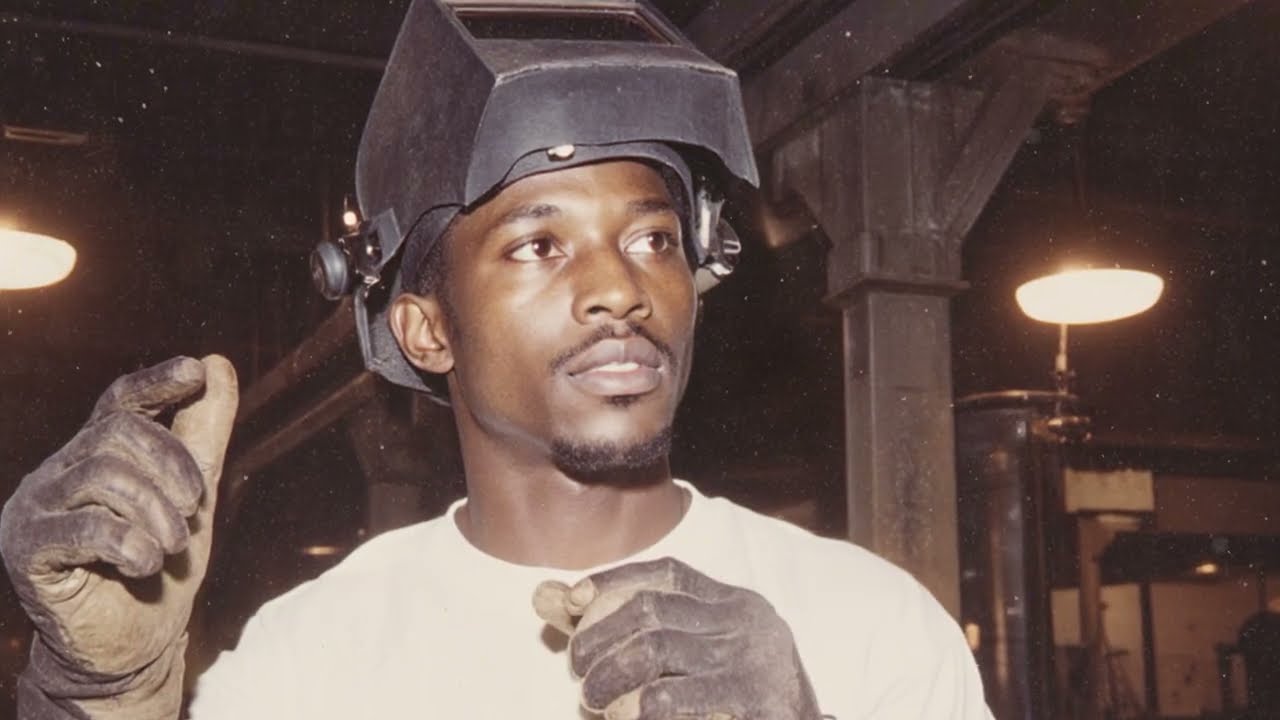

In one of those brick houses, 41‑year‑old Franklin Dorsey was packing for a weekend that, on paper, sounded ordinary. He was a union welder at the Red River shipyards, used to long hours, heat, and the kind of job where one wrong move could land you in the ER. Dependable, steady, not the type to chase whims—that was how people described him.

That morning, before sunrise, he moved deliberately. Hunting gear, clothes, food into a cooler. He loaded it all into his green 1977 Chevrolet Silverado—a truck that was basically an extension of him. He and his wife, 37‑year‑old Gloria, lived on a quiet street where everyone knew everyone’s vehicles. That Silverado was as recognizable as his face.

Around 5:15 a.m., the truck pulled away from the curb.

Later, Gloria would tell deputies that Franklin said he was headed for a two‑day hunting trip at Kisatchie National Forest, a few hours south, planning to be back Sunday evening.

Sunday came and went. No call. No sighting.

By Monday morning, unease hardened into something else. Gloria called the Caddo Parish Sheriff’s Office and reported her husband missing. Deputies opened a file, logged his information, and did what you do when a man says “hunting trip” and doesn’t return—they focused on the woods.

Search crews with dogs went into Kisatchie, working through campgrounds and popular trails. Rangers checked creeks, back roads, narrow clearings you’d only know if you’d hunted there for years. But there was no sign of Franklin. No shell casings, no campsite, no green Silverado parked under pines.

Then investigators noticed a gap that didn’t fit the “lost hunter” picture.

At the main entry station, a ranger pulled the handwritten log of vehicles for that weekend. They relied on staff to jot plates as cars rolled in—an imperfect system, but still a record. Franklin’s license plate was nowhere.

The ranger on duty that weekend said he never saw a green ’77 Chevy matching that description pass through the gate or park in the main lots. It was possible they missed something, sure. But that absence felt louder than it should have.

Taken together, those details pointed in a new direction: Franklin might never have driven into Kisatchie at all.

Deputies turned back to Gloria.

Under questioning, she mentioned something that made several pens pause over notebooks. Shortly before he disappeared, Franklin had increased his life insurance coverage to $380,000, naming her as the sole beneficiary.

“Why the increase?” they asked.

“He was worried,” Gloria said. “The shipyard is dangerous. He wanted to make sure I was protected if something happened.”

On its face, it made sense. Welding is risky. Men in risky jobs often carry higher policies. But the timing lodged itself in the investigators’ minds: a substantial bump in coverage, then a sudden disappearance, then a supposed hunting trip no forest ranger could confirm.

Three weeks later, Gloria walked into the sheriff’s office with something new: a letter.

It was typed, signed “Franklin,” and postmarked Dallas, Texas. It was short, almost brutally so.

“I can’t take the pressure. I need a new life. Don’t follow me.”

The tone roughly matched how he wrote, Gloria said. She turned it over as proof that he’d chosen to leave.

Forensic techs examined it. The only clear fingerprints belonged to Gloria. No Franklin. No unknown third party.

It didn’t prove she wrote it, but it didn’t prove he did, either.

With no body, no truck, and a note that could be read as a man reaching his breaking point, the sheriff’s office made a decision.

By December 1989, they reclassified the case. Officially, Franklin was no longer an ordinary missing person. He was logged as someone who had voluntarily walked away.

Search teams were called back. Field operations shut down. The hinges of the case swung quietly from “find him” to “he left.”

In June 1990, they checked again. His Social Security number showed no activity—no new job, no benefits, no tax filings. His bank accounts were frozen in time. No withdrawals. No deposits.

Ironically, that inactivity seemed to confirm their theory: he’d gone off grid on purpose.

With no new leads, deputies trimmed the file, removed what they considered redundant reports, and sent the boxed‑up case into storage. On paper, at least, it was over.

But Franklin’s family didn’t buy it.

His younger brother, Curtis, never once accepted the idea that Franklin woke up one day and decided to vanish.

“He wouldn’t leave his daughter,” Curtis told anyone who would listen. “He wouldn’t leave our mama. That’s not who he is.”

He repeated it to relatives, friends, and—over and over—to law enforcement.

The official record didn’t change, but Curtis’s refusal to move on became its own quiet kind of testimony.

A man had disappeared. A truck nobody could find. A forest that never saw him and a letter that only carried his wife’s prints. The file said “voluntary,” but the people who knew him best called it something else: wrong.

Months after Franklin vanished, Gloria stayed in their brick home on Pinehill Drive, breathing the same walls that held the last morning she saw him.

Then, in May 1990, she put the house on the market. She sold, moved across town to an apartment complex, leaving behind the neighborhood where Franklin’s truck used to sit and where Curtis still drove by, hoping to see something different.

She got a clerical job at a local housing authority. Steady hours. Reliable pay. On the surface, it looked like a woman picking up pieces.

At the same time, she started knocking on another door: the one with $380,000 behind it.

The life insurance policy Franklin had boosted carried a clause for disappearance—if a court issued a finding of presumed absence, the company could pay out.

With an attorney’s help, Gloria filed a petition. She brought notarized statements from people saying they hadn’t seen Franklin and considered him missing. The legal process stretched through 1990.

By year’s end, the court issued a ruling: presumed absent.

That ruling unlocked money. Not all at once—insurers rarely write a single check and walk away. But enough. A partial payout first.

She kept pushing. Filing, documenting, swearing under oath that Franklin was gone.

By 1993, records showed the remaining funds were released. The policy that had seemed like a safety net in case of a shipyard accident had now become the backbone of Gloria’s new life.

She moved into a larger apartment. Upgraded her old sedan to a newer Buick.

Neighbors described her as quiet, private. When they pressed about her husband, she’d say, “He’s gone,” and little else.

She never filed for divorce. On paper, she remained Mrs. Dorsey. But on forms and applications, she began using Carter—her maiden name.

By late 1991, a new man was in the picture: 45‑year‑old part‑time mechanic, Harold Benton.

Public records later showed he had a record—burglary, prior arrests. That didn’t stop the relationship.

By 1992, Harold was living with Gloria, the same address, their tax filings matching. No marriage license, but no need to pretend he was just “a friend” either.

The early ’90s passed quietly for them. Gloria appeared stable. In 1993, she bought a small rental house using part of the insurance settlement. Two years later, she refinanced, signing affidavits stating Franklin had ceased all contact and was presumed dead. Each one was a small legal brick, building a wall around a version of events where Franklin had simply vanished and stayed gone.

Curtis kept knocking on the other side of that wall.

In 1994, he asked the sheriff’s office formally to reopen the case. He pointed to Franklin’s union membership, steady job, his daughter, their mother. “This doesn’t make sense,” he argued.

Deputies looked over the dusty file. They saw what they’d always seen: a missing man, a note, a lack of activity.

“No new evidence,” they concluded. Case stays closed.

Meanwhile, Harold’s name popped up occasionally in minor traffic stops.

In 1996, he was pulled over twice for expired tags. In 1997, again—this time for driving a vehicle not registered in his name.

Officers ran the visible VIN on the dashboard. The checks came back muddy, nothing concrete. No one crawled under the truck to examine the frame VIN, which is harder to alter and far more permanent. In those days, for a basic stop, that wasn’t unusual.

The vehicles were released. The paperwork filed.

Nobody realized they were letting a key piece of 1989 roll back out onto the road.

By the mid‑’90s, the story of Franklin’s disappearance had settled into an uncomfortable peace.

On paper: voluntary.

In Gloria’s life: insurance, new partner, slowly stacking assets.

In Curtis’s gut: something rotten that nobody wanted to smell.

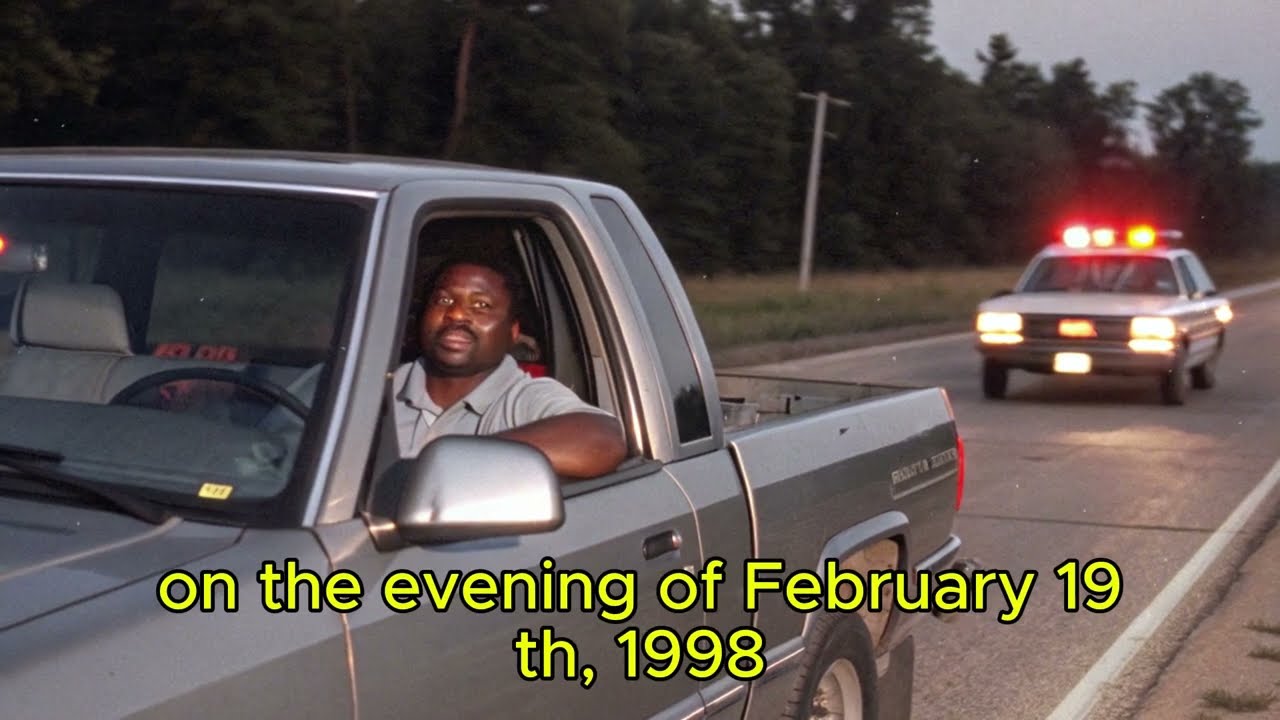

Then came February 19, 1998.

On Highway 6 in Natchitoches Parish, a Louisiana state trooper noticed that primer‑gray Silverado. Mismatched plates. Sketchy paint. Tampered license bracket.

He pulled it over. The driver, a Black man in his late forties, said his name was “Daniel Brown.” No license. No proof.

The trooper ran the VIN. This time, not just the dashboard plate. He checked the frame.

An alert flashed:

Vehicle registered to Franklin Dorsey, Shreveport. Reported missing November 1989.

Nine years.

The driver was arrested and taken to the parish jail.

Fingerprints revealed the truth: not Daniel Brown.

Harold Benton.

The same man living with Gloria Carter for years.

That connection—a long‑missing man’s truck in the hands of his wife’s partner—was the first real pulse in a case that had been clinically dead for almost a decade.

Under questioning, Harold shut down. “I want a lawyer,” he said. And that was that. No explanation how he’d gotten the truck. No story about a bill of sale.

So investigators turned their attention to the Silverado itself.

They impounded it, rolled it into a forensic bay, and went over it inch by inch.

It had been repainted from green to primer gray. The dashboard VIN plate showed signs of filing, an attempt to throw off checks. But the frame VIN told the real story—it was Franklin’s truck.

Inside, under the passenger seat, they found a weathered leather wallet.

Inside that wallet:

– Franklin’s union ID card.

– A faded photo of Franklin and Gloria, dated 1985.

– A Shell gas receipt from Natchitoches, Louisiana, timestamped November 4, 1989.

That last detail hit like a hammer.

The receipt placed Franklin’s truck in Natchitoches Parish the day after he supposedly drove south for a hunting trip in Kisatchie. The forest where he’d allegedly vanished was in one direction; the gas receipt said his truck went somewhere else entirely.

The wallet. The receipt. Harold behind the wheel.

Those weren’t loose threads anymore. They were a rope pulling the whole story in a new direction.

With the truck and what it held, the Dorsey file officially reopened. Detectives who had once condensed the paperwork now pulled everything back out.

Within a week, they had enough to take the next step.

They drafted an affidavit, laid out the Silverado connection, the wallet, Harold’s ties to Gloria, and went to a judge.

They walked away with a search warrant for Gloria Carter’s apartment.

This time, they weren’t looking for a man who walked into the woods. They were looking for proof that he never left home. The hinged sentence here: one stop for mismatched plates had turned a “voluntary disappearance” into the opening scene of a conspiracy case.

On March 2, 1998, investigators from Caddo and Natchitoches parishes showed up at Gloria’s place with that warrant.

They were authorized to seize financial records, letters, anything that could tie Gloria or Harold to Franklin’s disappearance.

They searched room by room.

In a hallway closet, tucked away, they found a small steel cash box. Locked. They pried it open.

Inside:

– Bundles of bank statements from the early ’90s.

– Correspondence tied with rubber bands.

– Draft letters typed in an old‑school typewriter font.

One draft letter stopped them cold.

Its wording and layout almost perfectly matched the Dallas letter Gloria had turned over in 1989—the one claiming Franklin had left because he “couldn’t take the pressure.”

But this version had a pasted template of a Shreveport postmark in the corner. It looked less like something that had been mailed and more like something someone had been practicing.

Forensic experts later compared the handwritten notes on the draft to samples from Gloria’s paperwork at the housing authority. The match was consistent.

The letters weren’t from a husband on the run. They were from a woman building a story.

The cash box held more.

A small brass key labeled “shed.”

The key didn’t fit anything in the apartment. But Franklin and Gloria’s old home on Pinehill Drive had a shed in the backyard.

Detectives contacted the new owners, explained the reopened investigation, and asked permission to look around.

Behind the house, the shed still stood—weathered wood, sagging roof, warped siding.

Inside, they started with the obvious surfaces, then looked deeper. Behind one warped interior panel, faint specks stained the wood. On the floor, under loose planks, a dark stain soaked into the boards.

They sprayed luminol. Under the chemical, the patterns glowed. Blood.

They took samples.

They also noticed disturbed soil near the fence. Digging a little, they unearthed a rusted metal box buried shallow.

Inside, wrapped in canvas, were personal items that time hadn’t erased:

– Franklin’s hunting license.

– A cracked wristwatch.

– A pair of worn leather boots.

Things a man would pack if he were planning to go into the woods. Things that shouldn’t be buried 20 feet from his back door if he’d actually gone.

DNA analysis of a hair found in the shed tied it to Franklin’s maternal line. The blood was human. The belongings were his.

Taken together, the message was clear: Franklin never made it to any forest.

Something happened at home.

His possessions were hidden on purpose. His truck was altered and eventually surfaced under Harold’s hands.

Detectives sat down with Gloria again.

“Explain the truck,” they said. “Explain the wallet. Explain the letters. Explain the shed.”

She denied everything. “He left,” she insisted. “He staged it. Not me.”

When they pressed about Harold driving Franklin’s Silverado, she clammed up.

Her story, already fragile, began to crumble under the weight of forged letters, hidden property, blood traces, and buried boots.

Harold, still in custody on vehicle charges, watched the walls inch closer.

With the physical and financial puzzle pieces now on the table, the district attorney’s office moved.

They took it to a grand jury.

On March 18, 1998, indictments came back against both Gloria Carter and Harold Benton.

The charges: conspiracy, insurance fraud, evidence tampering, and related counts.

The missing person case had officially become a criminal conspiracy. No body. No murder charge. But the implication was as loud as any headline.

The joint trial started in November 1998 in Caddo Parish.

The courtroom buzzed—not just because of the drama of a vanished man and a repainted truck, but because the state was building almost everything on circumstantial evidence.

The prosecution laid out its pillars:

– The forged Dallas letter.

– The shed blood and buried belongings.

– The recovered Silverado with Franklin’s wallet inside.

– The $380,000 life insurance payout that had funded Gloria’s new life.

Assistant District Attorney Lionel Brooks told the jury plainly: “Franklin didn’t walk away. He was removed. And his disappearance was turned into a payday.”

They called Curtis first.

He spoke about his brother’s loyalty to family, his job, his little girl, their aging mother. “He wasn’t perfect,” Curtis admitted, “but he didn’t run. He stayed. That’s who he was.”

Shipyard coworkers followed. One remembered Franklin saying he didn’t like how often Harold was around the house. Another recalled him worrying out loud about tension at home.

Those details weren’t proof of violence, but they sketched a motive: tension, third‑party presence, money on the line.

Handwriting experts took the stand, comparing the original Dallas letter with the drafts from Gloria’s cash box. The marginal notes, the mistakes corrected the same way, the formatting—it all pointed back to one person.

“Franklin did not write this,” an examiner testified. “Ms. Carter did.”

Forensics walked the jury through photographs of the shed. Luminol‑lit images on display showed bright traces against dark wood. They explained DNA analysis, the hair tied to Franklin’s maternal line, the buried metal box with his boots, watch, and license.

Then came the Silverado.

Jurors saw photos of its primer‑gray paint, the tampered VIN plate, the wallet under the seat, the 1985 photo of Franklin and Gloria, the Shell receipt from November 4, 1989 in Natchitoches.

Each piece stacked on the last.

The defense tried to pry them apart.

Harold’s attorney reminded the jury: no body, no murder weapon, no eyewitness to violence. “My client may have ended up with a truck he shouldn’t have had,” he argued, “but that doesn’t make him a killer.”

Gloria’s lawyer painted her as a woman abandoned and forced to survive. He pointed to her steady job, her attempt to keep bills paid. He suggested the letters and paperwork were the panicked acts of someone scrambling to get closure and financial stability after being left behind.

But cross‑examination cut through that image.

The prosecution highlighted that Gloria applied for insurance payouts within weeks of Franklin’s disappearance. They showed how she refinanced properties years later, swearing in affidavits that he was dead—without ever having a body or official death certificate.

They laid out the timing:

– Policy boosted to $380,000.

– Franklin vanished.

– Dallas letter “appeared.”

– Truck gone.

– Years later, truck reappears under Harold.

– Insurance money used to buy real estate and a Buick.

In closing, ADA Brooks put it bluntly:

“Motive: $380,000. Method: forge, hide, and lie. Result: a man disappears on paper, his memory buried like his belongings in that shed.”

On December 10, after a week of testimony and seven hours of deliberation, the jury came back.

Guilty on all counts.

On December 21, 1998, sentencing closed the loop.

Judge Raymond Dupri addressed Gloria first.

He gave her 28 years at the Louisiana Correctional Institute for Women. He cited her “cold manipulation of trust” and her calculated use of financial systems to profit off disappearance.

Harold received 18 years at Angola State Penitentiary. His role was deemed “integral”—not the mastermind, but the man behind the wheel of the stolen past.

Both were barred from parole consideration for at least the first 10 years.

Neither was convicted of murder. Without a body, the state had stayed away from homicide charges and instead built their case on conspiracy and fraud.

The insurance company demanded its $380,000 back. Investigators testified that most of it was gone. Property deals, vehicles, everyday living. The court signed a restitution order that everyone knew was more symbolic than practical.

Curtis finally got to speak formally.

“My brother was not a ghost,” he told the judge. “He worked. He provided. He trusted the wrong person. They buried his memory for nine years. But the truth finally came back.”

Outside, newspapers called it one of the most complex disappearance prosecutions in Louisiana in the ’90s. Commentators talked about how you can secure convictions without a body if you document everything else—blood, forged paper trails, financial gain, repainted trucks.

Franklin’s file was updated one last time.

Status: presumed homicide, exceptional clearance by conviction.

The green‑turned‑gray Silverado that had reignited the case was permanently seized and shipped to state evidence storage in Baton Rouge. Stripped of false paint, tagged, and shelved, it became one of the only physical links to Franklin still in state custody.

By the end of 1998, the legal side of the Dorsey case was done. No remains. No marked grave. Just sentences for Gloria Carter and Harold Benton, a family left to grieve a man the system had initially written off, and a hard lesson about what a $380,000 policy can look like when greed and betrayal enter the picture.

Somewhere in an evidence warehouse, that old Silverado still sits under fluorescent lights, dust collecting on its hood, the US flag decal long scraped away. It’s quiet now, but if you trace its VIN, it tells the same story it did the night the trooper pulled it over: Franklin never walked away. Someone drove his life out from under him and thought the road would never circle back.

News

Soldier Infects 20 Y/O Pregnant Wife With 𝐇𝐈𝐕 After SECRET 𝐆𝐀𝐘 Affair with Commandant | HO”

Soldier Infects 20 Y/O Pregnant Wife With 𝐇𝐈𝐕 After SECRET 𝐆𝐀𝐘 Affair with Commandant | HO” At 20 years old,…

60 YO Man Travels to Barbados to Meet His Online Lover, Only to Discover She is A Dw@rf, It Led to.. | HO”

60 YO Man Travels to Barbados to Meet His Online Lover, Only to Discover She is A Dw@rf, It Led…

40 YO Gigolo Travels to Cayman Island to Meet Online Lover–48 HRS LTER He’s Found 𝐖𝐢𝐭 𝐌𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐎𝐫𝐠𝐚𝐧𝐬 | HO”

40 YO Gigolo Travels to Cayman Island to Meet Online Lover–48 HRS LTER He’s Found 𝐖𝐢𝐭 𝐌𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐎𝐫𝐠𝐚𝐧𝐬 | HO”…

2 Days After 60 YO Woman Arrived in Bahamas to Meet 22 YO Online Lover, Her B0dy Washed Up at Sea | HO”

2 Days After 60 YO Woman Arrived in Bahamas to Meet 22 YO Online Lover, Her B0dy Washed Up at…

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case | HO”

Young Man Vanished in 1980 — 10 Years Later, a Flea Market Find Reopened His Case | HO” One internship…

Newly Wed Pastor 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 Virgin Wife Immediately He Saw D Tattoo On Her Breast on their Wedding Night | HO”

Newly Wed Pastor 𝐊𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐬 Virgin Wife Immediately He Saw D Tattoo On Her Breast on their Wedding Night | HO”…

End of content

No more pages to load