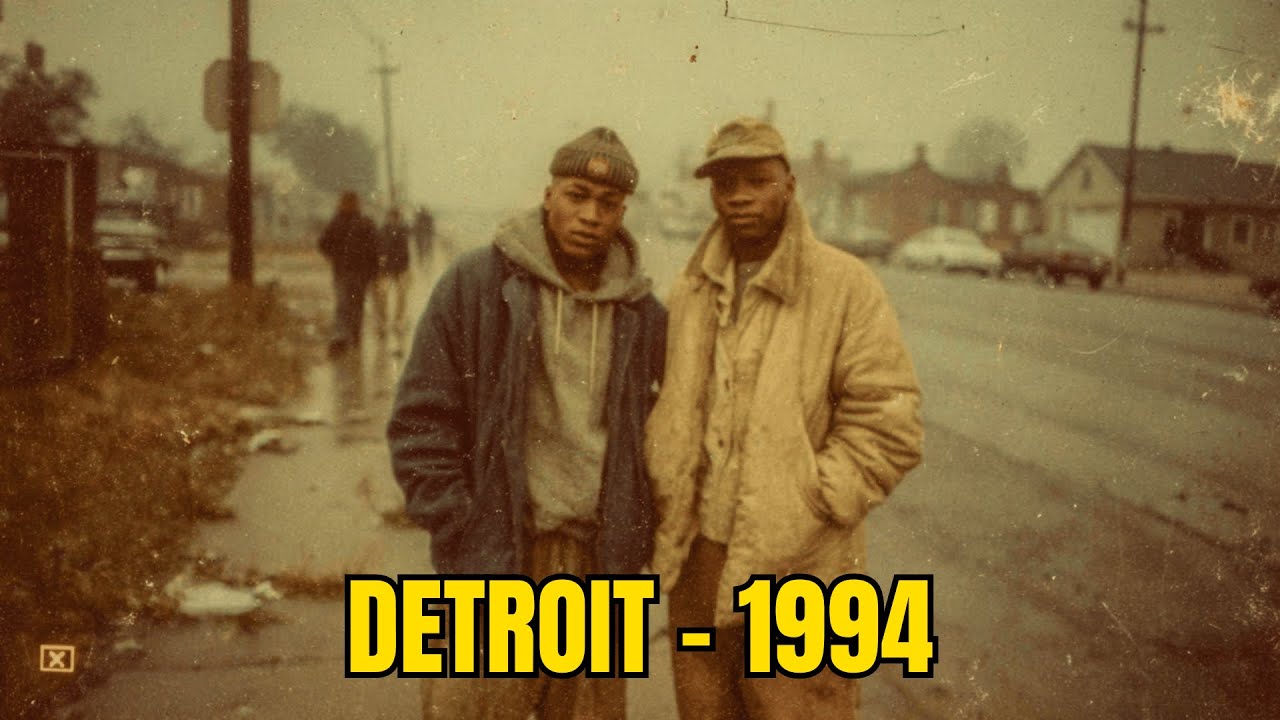

Blood Night in Detroit: The Marshall Brothers Who Burned 11 Gang Members Over a Parking Lot Dispute | HO”

On the night of June 3, 1994, eleven young men were trapped inside an abandoned house on Greensboro Street on Detroit’s east side when flames took the structure faster than anyone could run. All of them belonged to a street crew that controlled three blocks of cracked territory. The men accused of setting the blaze weren’t gang rivals or drug bosses.

They were two middle-aged brothers—Raymond and Marcus Marshall—former auto workers, churchgoing family men, the kind of neighbors who once fixed your porch steps without asking for money. The FBI would later call it one of the most extreme acts of civilian retaliation in Detroit’s modern history.

And the reason behind the inferno wasn’t drugs, wasn’t gang warfare, wasn’t self-defense in the moment. It was an empty lot the size of four parking spaces, and the complete collapse of every system that was supposed to protect law-abiding people from the chaos swallowing their street. In Raymond Marshall’s kitchen, a little magnet shaped like a U.S. flag held his utility bill to the refrigerator door, a cheap patriotic souvenir from better years, and that tiny square of red-white-and-blue would watch him decide he was done asking for help.

The hinged truth is this: when a city stops answering 911 with action, the desperate start answering themselves.

Detroit’s east side in 1994 was a war zone that didn’t make the evening news anymore because war had become routine. The city recorded 541 homicides that year—one every sixteen hours. In the neighborhood between Harper Avenue and Outer Drive, where Greensboro Street cut through blocks of brick worker houses built in the 1940s, the population had dropped from 14,000 in 1970 to barely 6,800 by 1994.

Every third house sat vacant, windows boarded with plywood tagged with warnings like KEEP OUT and DONT GET SHOT, as if a slab of wood could negotiate with desperation.

Summer arrived early that year. By the first week of June, the temperature pushed into the low 80s by midafternoon. The air smelled like tire smoke from a fire three blocks over that had been smoldering for two weeks, fried food from the corner store that sold more single cigarettes than packs, and something sweet and chemical everybody recognized but didn’t name out loud.

At night, when it cooled into the mid-60s, you could hear everything—dogs barking at shadows, bass thumping from cars with sound systems worth more than the cars, sirens that had become background noise, and gunshots that didn’t always earn a call because calling the police felt like praying to a God who stopped listening years ago.

The economic catastrophe that gutted Detroit in the 1970s and ’80s had settled into a kind of permanent apocalypse by the mid-’90s. Plants that once employed 200,000 workers had closed or moved. In neighborhoods like Greensboro Street, unemployment hovered around 38%.

For Black men over 40 without a college degree, men who’d spent their adulthood on assembly lines, it was closer to 65%. When Chrysler shut down its Jefferson Avenue plant in 1991, it didn’t just erase jobs. It erased futures. It erased the American promise that if you worked hard and played by the rules, you could build something that lasted.

Into that vacuum poured crack cocaine, arriving in Detroit in the mid-’80s and turning street economics upside down. A teenager with no prospects could make more money in a week than his father made in a month—if he accepted fear as currency and violence as a business expense. If you controlled fear, you controlled everything.

Raymond Earl Marshall was 47 in June 1994. Six-foot-one, broad shoulders still carrying the muscle memory of twenty-two years lifting and installing windshields on the Chrysler line. His hands were huge, scarred and calloused, knuckles broken and healed crooked from factory accidents. A scar cut across his right eyebrow from a piece of flying metal in 1979 that took twelve stitches and nearly took his eye. On cold mornings, he walked with a slight limp, the legacy of a herniated disc the company insurance never fully treated.

Every morning he woke at 5:45 out of habit even after the plant shut him out of his own life. He made coffee in the same Mr. Coffee machine he’d owned since 1983, sat at the kitchen table, and read the Detroit Free Press front to back as if the print could still explain why the city felt like it was sinking. He still wore work boots and Carhartt pants, as if dressing for a job might summon one.

By 7:00 a.m., he was outside checking the small vegetable garden ClaraGene planted, fixing whatever needed fixing on their Greensboro Street house, and watching the empty lot three houses down that had belonged to his family since 1976.

The hinged truth is this: when everything else is taken from a man, he will cling to the last thing that still feels like his.

Raymond married ClaraGene Thompson in 1969, right after Chrysler hired him. ClaraGene worked in the cafeteria at Henry Ford Hospital, small and quick and sharp-tongued, raising three kids on two working-class incomes while the city cracked around them. Their oldest, Raymond Jr., was 24 and worked mall security in the suburbs. Their daughter, Kesha, 21, was a nursing student at Wayne County Community College. Their youngest, Marcus—named for Raymond’s brother, not to be confused with him—was 19 and doing a year in county jail for possession with intent, a fact Raymond carried like a stone in his chest.

What Raymond valued most wasn’t money—good thing, because by 1994 he didn’t have any. What he valued was order. Structure. The belief that there were still boundaries and still rules, and that decent people weren’t supposed to be punished for trying to live decently.

When Chrysler eliminated his position in May 1991, Raymond got a severance check for $8,400 and a handshake from a supervisor who wouldn’t meet his eyes. Three months later, unemployment benefits ran out. By 1994, the Marshall household lived off ClaraGene’s salary and the savings the couple had built over twenty-two years, watching the account shrink the way you watch a shoreline disappear under rising water.

The empty lot on Greensboro Street was a quarter acre of cracked asphalt and weeds squeezed between Raymond’s childhood house—now owned by his cousin Dennis—and a burned-out shell from Devil’s Night 1989 that the city never demolished. Raymond’s father, James Earl Marshall, bought the lot in 1976 for $3,200 with a dream: maybe a garage, maybe a small repair business, maybe just a place for barbecues and dominoes and a neighborhood that felt like a neighborhood.

James Marshall died in February 1989 of a heart attack while shoveling snow. He left the lot to Raymond and his younger brother Marcus with one handwritten instruction: keep it clean, keep it open, let the neighborhood use it. For five years, the brothers honored that. Filled potholes, painted over graffiti, chased off squatters. The lot became unofficial community parking, a place kids played basketball on a hoop Marcus installed in 1990. A small patch of order in a street that had forgotten what order looked like.

That ended in March 1994.

Marcus Allen Marshall, Raymond’s brother, was 43 that spring, five-nine, always in a Detroit Tigers cap pulled low. He had the wiry build of a man who moved fast and stayed alert. He followed Raymond onto the Chrysler line in 1973, worked eighteen years until the same layoffs erased him in 1991. Unlike Raymond, Marcus never married, never had kids, never built a life designed to survive catastrophe. He drifted—unemployment, then disability for a back injury that was real but not as disabling as he claimed, spending most of his time at Raymond’s house, playing dominoes and talking about how the world had cheated them.

The brothers were different in temperament but identical in one crucial way: they believed a man had to draw lines and defend what was his, even when the world seemed designed to take it.

The East Side Kings weren’t a gang with colors and a national name. They were a loose collection of young men, 16 to 28, controlling drug territory on Greensboro between Outer Drive and Harper—three blocks, maybe forty houses, half vacant. Small-time by Detroit’s standards. But in the lives of the sixty or seventy families still trying to live normal lives on those blocks, the Kings were everything: the reason kids didn’t play outside after dusk, the reason strangers knocked on the wrong doors, the reason property values had dropped to nothing.

Demetrius Lamont Williams—Dime—was 22 in spring 1994. Five-ten, maybe 150 pounds, crown tattoo on his neck, eyes older than his face. He’d been raised by a mother struggling with addiction. His father was doing fifteen years in Jackson for armed robbery. Dime dropped out of high school because he did the math: a diploma earned minimum wage; selling crack earned $1,200 a week. By 1994, he controlled the Kings not by being the toughest but by being the smartest. In a crack economy, intelligence mattered. And fear mattered more.

The crew operated out of three abandoned houses, with 1847 Greensboro as the main one: a condemned two-story brick structure, boarded windows, door frame splintered from being kicked in too many times. First floor for business around the clock. Second floor for sleeping on stained mattresses, rotating shifts so someone stayed awake downstairs.

The hinged truth is this: when fear becomes the neighborhood currency, the people with the least to lose start collecting it from everyone else.

The conflict began Friday afternoon, March 4, 1994. Raymond drove to the lot around 3:30 p.m. as he did every few days. He saw the chain-link gate Marcus installed torn off its hinges and thrown into weeds. The lot was crowded—young men he recognized and some he didn’t, cars parked at angles, music thumping, open-air transactions happening fifteen feet from the street like the lot was a stage and no one expected consequences.

Raymond parked his 1987 Buick LeSabre, got out slowly, and approached the nearest group.

“This is private property,” he said, keeping his voice level. “Y’all need to move on.”

The closest young man—Terrence Davis, T-Bone—looked at Raymond like he’d spoken a dead language.

“Old man,” T-Bone said, “you need to get back in your car.”

“This lot belongs to me and my brother,” Raymond said. “Our father—”

“Your father don’t care whose lot it was,” T-Bone cut in. “It’s ours now. Unless you want problems, you best bounce.”

Raymond stood there long enough to understand the math: escalate and lose, or leave and try another route. He chose the second, drove home, told Marcus.

Saturday, March 5, both brothers returned. The lot was even more crowded. This time Raymond walked straight up to the young man who seemed in charge—the crown tattoo on his neck.

“I’m Raymond Marshall,” Raymond said. “This lot belonged to my father. It belongs to me and my brother now. We need you to respect that and conduct your business elsewhere.”

Demetrius “Dime” Williams studied Raymond with an expression that wasn’t hostile so much as curious, like he couldn’t understand why a man in work boots believed words still worked.

“Mr. Marshall,” Dime said, calm, almost polite, “I respect this lot got history for you. But we need this space. We got customers expect us here. We got a business. So here’s what’s gonna happen. You and your brother let this go, and we’ll make sure nobody mess with your houses or your family. That’s the deal.”

Raymond felt his jaw tighten. “That’s not a deal. That’s you taking what’s mine.”

Dime’s smile disappeared. “Yeah,” he said. “That’s exactly what it is.”

Raymond and Marcus went to Detroit Police. March 7. They filed a report at the 7th Precinct on Gratiot Avenue. A desk officer typed it up and said someone would follow up. Nobody did. March 14, same station, different officer, same promise, same result.

Over the next ten weeks, the Marshall brothers made fourteen documented calls to DPD about illegal activity on their property. Some calls logged, some not. Twice, patrol cars drove by slowly with windows up and never stopped. Once, an officer got out, spoke to Dime for about ninety seconds, got back in, and left.

That was the response to citizens reporting their property seized by a street crew.

By late May, Raymond stopped expecting help. Every morning he drank coffee and stared at that lot three houses down, watching young men arrive and leave, watching transactions happen where his father once grilled burgers on the Fourth. Every morning something inside him hardened from hurt into something colder and far more dangerous.

On May 28, the brothers sat on Raymond’s back porch, drinking beer, watching the sun drop behind boarded houses.

Marcus broke the silence. “We gonna let them take it?”

Raymond stared at the yard. He answered quietly. “No.”

“What you thinking?” Marcus asked.

Raymond spoke slowly, like he was testing the words in his mouth. “I’m thinking if the law won’t protect what’s ours, we got to protect it ourselves.”

Marcus nodded, took a long pull. “That’s a line, Ray. Once we cross it—”

“I know.”

“ClaraGene know what you thinking?” Marcus asked.

Raymond’s eyes stayed forward. “ClaraGene don’t need to know.”

Marcus stood, hesitated at the steps. “You sure?”

Raymond looked at him, the brother he’d worked beside for eighteen years, the brother who understood pride and loss the same way. “Yeah,” Raymond said. “I’m sure.”

What Raymond didn’t know was that the choice made on that porch would end with eleven dead, two brothers in prison for life, and a neighborhood marked by one night when desperation and rage collided with fire.

The hinged truth is this: the moment a decent man decides he’s done asking, the world should get quiet—because something is about to break.

The decision didn’t lead to instant action. It led to a slow transformation over four weeks, during which two men who’d lived by rules began to break them with methodical care.

The last normal Sunday in the Marshall house was May 29. Raymond woke at 5:45, made coffee, and by 8:30 wore his one good suit—navy, bought in 1987 for his mother’s funeral. ClaraGene wore a yellow dress with white flowers. They drove to New Hope Baptist Church on Harper Avenue, the church Raymond had attended since he was seven, back when the neighborhood still believed in stability. Service ran until noon. They stood on the steps afterward with people they’d known for decades—men who once worked Ford until their bodies quit, women whose sons were away for things nobody discussed directly. Everyone carried the same weight.

Raymond Jr. met them for lunch downtown at Fishbones, bringing his girlfriend Tamika. The restaurant was loud with families and kids, cornbread steaming on plates, gospel low under conversation. Raymond Jr. said, “I’m thinking about proposing. Maybe next month. Wanted to ask what you think.”

Raymond studied his son—twenty-four, trying to build something in a city designed to tear things down—and saw his own younger self, believing hard work would be enough.

“You love her?” Raymond asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“Then ask her,” Raymond said. “Don’t wait for perfect time. There ain’t no perfect time.”

ClaraGene squeezed his hand. For ninety minutes Raymond forgot the lot. Forgot Dime. Forgot everything except family and food and the illusion of normal.

Walking to the car, ClaraGene said, “You been quiet lately.”

“Just got things on my mind,” he said.

“What things?” she pressed.

Raymond unlocked the Buick and opened her door like he always did. “Nothing you need to worry about.”

ClaraGene looked hard at him. She wasn’t blind, but she knew her husband well enough to know pushing could make him disappear behind silence.

“Raymond,” she said carefully, “whatever you thinking about doing…”

“I’m not thinking about doing anything,” he lied.

Monday morning, May 30, he called the 7th Precinct again. The fifteenth time he’d asked for help.

“Sir,” the desk officer said, bureaucratic exhaustion bleeding through his tone, “we’re aware of the situation on Greensboro, but unless there’s an immediate threat to life or property, there’s not much we can do. We’re understaffed. Homicide rate—”

Raymond hung up mid-sentence, standing in his kitchen holding the receiver, listening to the dial tone like it was the city’s heartbeat: steady, indifferent, useless.

Marcus came over that afternoon. They sat in Raymond’s garage, drinking Stroh’s beer, listening to bass thump somewhere nearby.

“Called the police again,” Raymond said.

Marcus nodded. “What they tell you?”

“They’re aware,” Raymond said, a sharp laugh. “But can’t do nothing unless there’s an immediate threat. Like fifteen or twenty dealers sixty yards from where we sitting ain’t a threat.”

Marcus watched Raymond with a look Raymond recognized from layoffs and funerals, from every moment the world demanded surrender or fight.

“So,” Marcus said, “what you want to do?”

Raymond lowered his voice. “I been thinking about how they operate. Most the crew clears out around two, three in the morning. Dime and six, seven others stay. They sleep upstairs in that big house. 1847.”

Marcus set down his beer. “You been watching them.”

“Every night,” Raymond said. “Customers stop coming around one-thirty, two. Everybody leaves except the core. They sleep upstairs.”

Marcus’s voice dropped. “Ray. You talking about what I think you talking about?”

Raymond didn’t answer directly. He walked to the workbench and pulled out a gas station road map of Detroit, unfolded it on the hood of the Buick. He’d marked three locations: his house, the lot, and 1847 Greensboro.

“House got boarded windows,” Raymond said, pointing. “Front door. Back door. Basement doors welded. They got their own people blocking exits at night ‘cause they paranoid about rivals.”

Marcus stared. “This is crazy.”

“Yeah,” Raymond said. “And once we do it, we can’t take it back.”

The garage went quiet, like the air itself was listening.

“What you need from me?” Marcus asked.

“Need you sure,” Raymond said. “Because once we start, we both in it.”

Marcus nodded slowly. “I’m sure.”

The first red plastic gas can showed up in the story on June 1, when Raymond drove to a hardware store in Dearborn and paid cash for three two-gallon cans, telling the clerk he was helping a friend with a lawn business. On June 2, Marcus bought three more from a different store in River Rouge. They filled them over a week at different stations, never more than two gallons at a time, never twice at the same place. By June 10, they had eighteen gallons stored behind winter coats in Marcus’s apartment.

Raymond began keeping a spiral notebook from CVS—cost 89 cents—logging patterns, times, license plates, the number of people inside 1847. Friday nights busy. Saturdays similar. Sundays slowest. The overnight core never exceeded eight. Dime always there. A teenager named Jamal. T-Bone. Ice. A handful of others Raymond didn’t know by name but knew by face.

The moral weight settled on Raymond in layers: first justification, then rationalization, then the cold understanding that he was about to become the kind of man he spent his whole life trying not to be.

One night in mid-June he sat at his kitchen table in darkness and almost stopped. The lot was just asphalt. Not worth this. He pictured his father, churchgoing, believing in law and God, and wondered what James Marshall would think.

Then Raymond pictured the last three years—layoff at 44, savings shrinking, neighborhood collapsing, fourteen calls to police that brought nothing, Dime’s face when he said, “That’s exactly what it is.”

Some lines, Raymond decided, you didn’t walk away from.

The hinged truth is this: a man can forgive losing money, but losing dignity—especially in public—can make him do unforgivable math.

The final weekend before it happened, June 18 and 19, Raymond performed normality like a man reading a script. Saturday he cut grass, washed the car, fixed a loose hinge. ClaraGene made pork chops. They watched a movie on Channel 7 Raymond couldn’t later recall. He sat on the couch with her head on his shoulder and felt like he was already gone.

Sunday they went to church again. Reverend Thompson preached forgiveness and mercy. The words washed over Raymond like water over stone: present, not penetrating. After service, ClaraGene introduced Raymond to a visiting niece from Chicago who talked about how Detroit used to be, how sad it was now. Raymond nodded, smiled, said polite things, while inside he counted hours.

That night, June 19, Raymond kissed ClaraGene goodnight at 10:30. She was half asleep after a double shift. He stood in the doorway watching her breathe, memorizing the curve of her shoulder under the blanket like a man studying the last page of a book he couldn’t reread. “I love you,” he whispered. She didn’t wake.

He went downstairs, dialed Marcus.

“Tomorrow night,” Raymond said. “Midnight.”

Marcus was quiet five seconds. “I’ll be there,” he said.

The time that mattered, the hinge on which everything would swing, would later be repeated by police reports and news anchors: 12:47 a.m., Friday, June 3, 1994.

At 12:47 a.m., Raymond drove to Marcus’s apartment with six gas cans in his trunk. At around 2:30 a.m., they parked three blocks from Greensboro and walked toward 1847 carrying gasoline and matches and the weight of a decision that couldn’t be undone.

What happened next would leave eleven dead, two brothers sentenced to die in prison, and a question Detroit still couldn’t answer decades later: at what point does a decent man become a monster, and who shares the blame when the systems meant to prevent monsters stop working?

The hinged truth is this: the moment you decide to punish the world with fire, you stop being a victim of the city—you become one of its disasters.

Part 2

Friday, June 3, 1994. The temperature had dropped into the mid-60s. Streetlights on Greensboro flickered—half burned out, never replaced—casting alternating pools of sick orange and deep shadow. A car alarm wailed somewhere, then quit. Sirens drifted in the distance and nobody moved toward them. Detroit’s soundtrack did what it always did: it kept playing.

Raymond sat behind the wheel of his Buick two blocks from 1847 Greensboro. Engine off. Hands on the steering wheel. In the trunk: six red two-gallon gas cans—eighteen gallons total. In his pocket: a matchbook from Lou’s Diner. He checked his watch. 12:51 a.m.

His hands were steady, which surprised him. He expected shaking. He expected nausea. Instead he felt cold clarity, like he was watching himself from outside his body. He looked down at his palms and thought, these are the hands that held my babies, fixed my porch, opened ClaraGene’s car door for twenty-five years. How can these be the same hands?

He stepped out quietly and walked to the corner where Marcus waited under a dead streetlight with three cans at his feet, wearing dark clothes, Tigers cap replaced by a knit cap pulled low.

Marcus nodded once. No words. They both carried their cans down Greensboro at a normal pace. In another city, two middle-aged men carrying gas cans at 1:00 a.m. would have been noticed. Here, nobody was watching. Nobody wanted to watch.

1847 Greensboro sat dark except for a dim light bleeding through cracks in boarded windows. Brick two-story built in 1948 for auto workers. Porch sagging. Door hanging crooked, frame splintered. Plywood on windows sprayed with tags and warnings. The brothers circled once, reading the house like a problem.

Back door chained with a padlock that looked tough but wasn’t. Ground-floor windows boarded tight. Second floor: three windows, two plywood, one cardboard taped from inside.

They set the cans in tall grass behind the house.

Raymond looked at Marcus. Whispered, “Last chance. We walk away now, nobody knows.”

Marcus shook his head. “We past that.”

Raymond picked up a can. Marcus picked up a can. They moved to the porch. Raymond unscrewed the cap and began pouring gasoline across wooden steps. The smell hit like a slap—sharp, chemical—mixing with the house’s other odors: decay, old smoke, residue that suggested this place had been used hard and cared for by no one.

Marcus worked the north side, soaking the foundation line. Raymond moved to the south side. They worked fast and quietly, eyes watering from fumes. Three cans emptied outside, lines laid like a plan you could smell.

Then Raymond tested the back door. The chain held, but the rotten frame gave. He looked at Marcus. Marcus nodded. They put their shoulders into it. One hard shove. The frame splintered. The chain stayed attached but the door ripped away and fell inward with a crash that sounded impossibly loud.

They froze.

Upstairs, movement. A voice: “Yo—what was that?”

No time left for pretending.

Raymond stepped into what had once been a kitchen. Cabinets torn off, sink full of trash, floor sticky. He poured the rest of his gas across the floor, feeding it toward the front room. Marcus emptied his can across the stairway, soaking each step until gasoline ran down like a dark river.

Footsteps above them, fast. Another voice: “Somebody poured—”

Then understanding, sharp and immediate.

Raymond pulled out the matchbook. For the first time his hands shook. This was the point of no return. He thought about the lot. He thought about fourteen calls. He thought about the desk officer saying “unless there’s an immediate threat.” He thought about Dime saying, “That’s exactly what it is.”

Marcus started to speak. “Ray—”

Raymond struck the match and dropped it.

The ignition didn’t need help. The house took the fire the way dry paper takes a spark. Heat surged. The stairwell lit up. The first floor filled with light that didn’t feel like light.

The voices upstairs changed—fear sharpening into panic.

Raymond and Marcus stumbled back through the broken frame and ran, not sneaking now, not caring about quiet. Behind them, the house began to roar.

They ran north on Greensboro toward Raymond’s parked Buick. Raymond didn’t look back, because looking back would mean admitting what the screams meant, and he couldn’t carry that and still run.

By the time they reached the car, his hands shook so badly it took three tries to get the key into the ignition.

They drove away at the speed limit, because Detroit police pulled over people for taillights and missed bigger things, because the habits of law-abiding men don’t vanish in one night even when those men have just committed the unforgivable.

On the block behind them, neighbors emerged onto porches, smelling smoke, seeing orange glow. A woman named Janice Thompson—62, three doors down—called 911 and told the operator, “There’s people trapped. There’s people inside and they can’t get out.”

The operator said fire units were on the way. Asked if anyone was attempting rescue.

Janice looked at the street: empty, still, nobody moving toward the heat. She answered quietly, “No. Nobody’s helping them.”

Because this was Greensboro Street in 1994, and people had learned that bravery didn’t always get rewarded—it often got you put in the ground.

Fire apparatus arrived within minutes of the call, but the speed of response couldn’t rewrite what had already happened. The firefighters did their jobs—hoselines, containment, calling for investigators—while understanding the awful truth professionals learn: some situations are beyond saving by the time you reach them.

By morning, the scene would become a mass-fatality investigation. Remains would be recovered. Names would be matched by dental records and what little survived. It would be called arson, and it would be called murder, and it would be called a massacre.

And while it was happening, three miles away, a White Castle on East 7 Mile kept its fryers hissing for the 2:00 a.m. rush. Onions sizzled. A radio played soft R&B. Detroit continued its normal Friday night the way it always did: peaceful on some blocks, violent on others, and numb everywhere.

Raymond pulled into his driveway six blocks from the fire far enough that he couldn’t see the glow, close enough that smoke rode the wind. He turned off the engine and sat in darkness, unable to move. Marcus in the passenger seat was crying—silent tears, shaking.

“What did we do?” Marcus whispered. “Ray… what did we do?”

Raymond stared at his hands. He tried to say the words he’d rehearsed.

“We did what we had to do,” he said.

His voice sounded hollow even to him.

Marcus shook his head. “Them boys was screaming.”

“Don’t,” Raymond said, voice cracking. “Don’t say it.”

They went inside. ClaraGene slept upstairs, unaware. Raymond showered as hot as he could stand and scrubbed his hands until they were raw. The smell wouldn’t leave. Smoke lived in skin the way guilt lives in a person: deep, stubborn, not coming off with water.

In the morning, Detroit woke to a ruined house on Greensboro Street and a body count that felt unreal even for a city used to blood.

Detective Sarah Chen arrived at the scene early, twelve years in homicide, the kind of investigator who could look at horror and still take notes. The arson investigator walked her through the basics: multiple points of ignition, strong evidence of accelerant, exits compromised. This wasn’t an accident. This wasn’t a spontaneous fight. This was planned.

“How many?” Chen asked.

“Eleven,” the arson investigator said, exhausted. “Second floor mostly. Some near windows.”

Chen stared at the brick shell and felt her detachment crack. Not because she’d never seen death. Because this was a different category: not a drive-by, not a targeted shooting, not the usual Detroit arithmetic. This was a whole room’s worth of lives ended at once.

“Witnesses?” Chen asked.

“One so far,” the investigator said. “Janice Thompson, 62. Saw two men around 12:50 a.m. carrying gas cans. Middle-aged. One taller.”

Sarah Chen asked about property ownership. 1847 was city-owned, condemned, never demolished due to budget. The Kings were squatting. Then she learned about the lot three houses down—private property owned by Raymond E. Marshall and Marcus A. Marshall. Fourteen calls to DPD logged between March and May reporting illegal activity and property dispute.

Fourteen.

Chen felt something click into place in a way she didn’t like. Not because it proved anything, but because it made a kind of awful sense.

“Get me everything on Raymond and Marcus Marshall,” she said. “Employment history. Records. Purchases. Everything.”

By the end of the next day, pieces stacked into a picture: two brothers laid off from Chrysler in 1991, no serious records, a lot claimed by a street crew, fourteen calls for help that went nowhere. Then a key detail: six red plastic gas cans purchased in early June, paid in cash—three in Dearborn, three in River Rouge. Not proof alone, but enough for a warrant.

Monday morning, June 6, Detective Chen and officers approached the Marshall home. Tactical backup came because no one knew if the brothers would resist.

Raymond Marshall was sitting on his porch drinking coffee like it was any other Monday, watching them arrive with an expression so resigned it almost looked like relief. ClaraGene stood in the doorway behind him, tears already on her face, as if she’d been crying since sunrise.

Chen introduced herself. “Mr. Marshall, I need to speak with you about the fire at 1847 Greensboro.”

Raymond set down his mug carefully, raised his hands slightly to show they were empty. “I expect you do,” he said.

Chen asked, “Were you involved in that fire?”

Raymond looked at his house, at his wife, at the empty lot three houses down. He didn’t stall. He didn’t run the way men run when they still believe escape is possible.

“Yes,” he said. “Me and my brother Marcus.”

Officers cuffed him. He didn’t resist. Marcus was arrested minutes later at his apartment. Also didn’t resist. Both waived counsel and gave full statements that afternoon. They described the planning. The gasoline. The match. They described it like men reciting an inventory list, because when you’ve spent your life on assembly lines, you learn to narrate work without emotion.

When asked why, Raymond’s answer was simple: “They took what was mine, and nobody would help get it back. What choice did we have?”

By Tuesday, Detroit split in half over the story. Some called the Marshall brothers heroes who did what police wouldn’t. Others called them murderers. Churches struggled to speak about it without taking sides, because taking sides meant deciding whose life counted more, and that’s a decision that stains the mouth of anyone who makes it.

Reverend Thompson at New Hope Baptist stood at the pulpit and asked the question the whole city was avoiding: why couldn’t two working men who followed rules find justice without fire, and why couldn’t the city protect people just trying to live?

The prosecution later had an easy argument: this wasn’t a moment of panic; it was days of planning, purchases, surveillance notes. Premeditation doesn’t disappear because you’re desperate. The defense argued systemic failure and extreme emotional disturbance. The jury understood Detroit. They lived Detroit. They still convicted.

In December 1994, Raymond and Marcus Marshall were found guilty on all counts. In January 1995, both were sentenced to life without parole. In court, Raymond said only, “They wouldn’t leave. What else was I supposed to do?” The judge answered quietly: keep calling. Call a fifteenth time, a sixteenth, a hundredth. You don’t become what you say you’re fighting.

Raymond died in custody years later after living quietly behind bars—teaching woodworking, no trouble, the kind of inmate you’d mistake for a grandfather if you didn’t know the file. ClaraGene never stopped visiting him until he was gone, carrying the burden of loving a man who did a terrible thing. Their children scattered and carried their own versions of the same impossible inheritance.

The victims’ families carried theirs too—because even if those eleven young men were dealing drugs, they were still sons, cousins, fathers, and the street doesn’t erase that. Funerals happened. Mothers collapsed. Babies grew up without fathers. The neighborhood quieted briefly, then filled again with new crews, new names, the same product, because the conditions that built the Kings—poverty, lack of opportunity, schools falling apart, law enforcement triage—didn’t vanish with one fire.

1847 Greensboro stood burned and hollow for years until the city finally demolished it. The Marshall family lot—the quarter acre that started everything—was sold in a tax auction and later became a community garden where children now plant vegetables. Most of them don’t know what their hands touch when they press seeds into the dirt.

The red plastic gas can appeared three times in this story: first as a purchase made in cash, then as evidence logged by detectives, and finally as a symbol of what happens when institutions fail and ordinary people start carrying their own solutions home from a hardware store.

The hinged truth is this: broken systems don’t just create crime—they create the belief that crime is the only language left.

News

Her Daughter Was Found Dead During Jamaican Carnival-10 YRS Later, She Saw Her Wit Twins & Her Husband | HO’

Her Daughter Was Found Dead During Jamaican Carnival-10 YRS Later, She Saw Her Wit Twins & Her Husband | HO’…

Dancing Dolls Tv Star Shot D3ad Moments After Her Dedicated DD4L Party | HO”

Dancing Dolls Tv Star Shot D3ad Moments After Her Dedicated DD4L Party | HO” Shakira grew inside that structure the…

The Appalachian Vendetta: The Harrison Brothers Who 𝑺𝒍𝒂𝒖𝒈𝒉𝒕𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒅 11 Lawmen After a Family D2ath | HO”

The Appalachian Vendetta: The Harrison Brothers Who 𝑺𝒍𝒂𝒖𝒈𝒉𝒕𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒅 11 Lawmen After a Family D2ath | HO” On the morning of…

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS | HO”

Two Sisters Vanished In Oregon Forest – 3 Months Later Found Tied To A Tree, UNCONSCIOUS | HO” In early…

FOUND ALIVE: Illinois Infant Abducted in 1990 Reunites After 23 Years | HO”

FOUND ALIVE: Illinois Infant Abducted in 1990 Reunites After 23 Years | HO” On the evening of August 2, when…

Man Ends 24 Year Marriage SECONDS After Wife Posted This… | HO”

Man Ends 24 Year Marriage SECONDS After Wife Posted This… | HO” The notification hit at 6:12 a.m., the kind…

End of content

No more pages to load