Atlanta Inmate Laughed At Guard’s 𝐕𝐚𝐠*𝐧𝐚 While 𝐇𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐒*𝐱, Found D3ad In His Cell.. | HO”

PART 1 — The Prisoner, the Rumors, and the Night No One Slept

In correctional institutions across the United States, rumor spreads faster than contraband. A single passing glance, an extra second of conversation, or a shift in routine can ignite an entire ecosystem of speculation inside the concrete walls. In the summer of 1988, inside a state correctional facility outside Atlanta, that combustible environment would become the backdrop to a tragedy that left one inmate dead, two others silenced by fear, and a community still searching for the truth decades later.

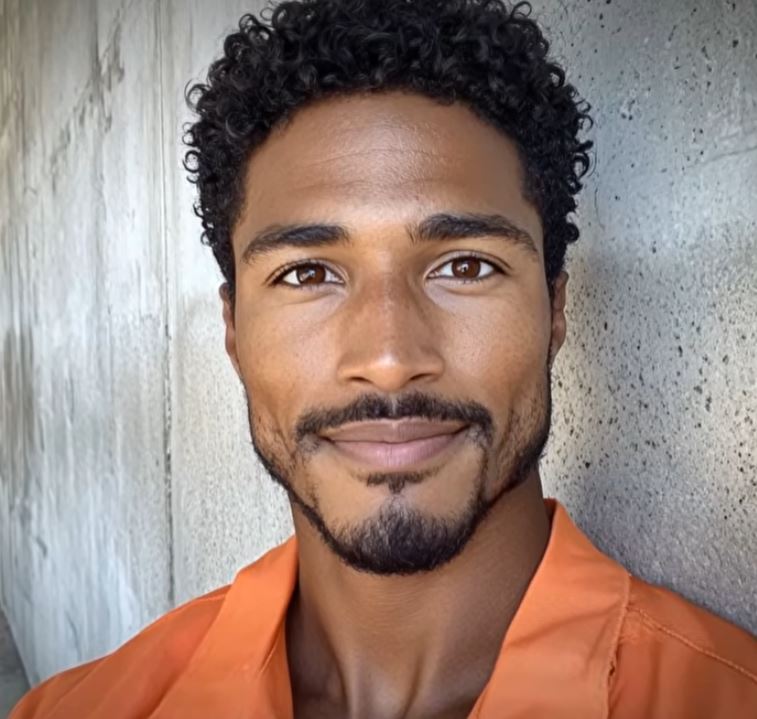

The day began like many others for Lamont Griffith, a muscular, soft-spoken man nearing the midpoint of his sentence. Griffith had been incarcerated long enough to grow accustomed to the rhythms of confinement: the metallic clank of doors, the watery oatmeal, the rigid timetables, and the understanding that privacy — emotional or physical — did not exist here. But in the weeks leading up to his death, small changes began to draw attention. Guards noticed. Inmates noticed. Griffith noticed most of all.

And it all revolved around one corrections officer.

Her name was Officer Rochelle “Relle” Devo — a woman known among inmates for her composure, discipline, and unwillingness to tolerate even minor rule violations. But beneath the image of firm professionalism that she projected, rumors began to grow that she and Griffith had developed an unusual familiarity. Eye contact that lingered too long. Brief conversations just out of earshot. Security sweeps that seemed to pause near his workstation.

In prison, perception can be as dangerous as reality.

Griffith’s two longtime cellmates — Jamal Rivers and Obiora “O” Wame — had watched the situation unfold with growing unease. Both men were seasoned enough to know that boundaries between staff and inmates were not simply rules; they were fault lines. Nothing good ever happened when those lines blurred.

But for Griffith, desire and isolation spoke louder than warning. He had been incarcerated eight years — eight years without intimacy, companionship, or the ability to be seen as anything more than a number on a uniform. If there was even a possibility that Officer Devo wanted something human from him — attention, connection, or the fantasy of something beyond the razor wire — he was willing to risk it.

According to Rivers and Wame, Griffith confessed what many others only suspected: Devo had approached him. First with innocent conversation. Then with small requests for help. Finally, with something else entirely — a whispered plan to meet at night under the pretense of a work assignment. A locked room. No witnesses.

For Griffith, it felt like oxygen.

For his cellmates, it felt like the prelude to a disaster.

That night, just before lights-out, Officer Devo appeared at the cell. Her voice was steady. Her request procedural. Griffith was needed for “laundry duty,” she said. He followed her out into the dimly lit hallway as his cellmates watched silently — a mix of curiosity, envy, and unease in their eyes.

He would never return alive.

The Encounter Behind a Locked Door

What happened in that storage room is now known only through the sworn statements of those who later discussed it privately — and through the terrified whispers of the men who heard what followed.

What began as a clandestine encounter reportedly turned volatile within seconds. Something was said — a nervous comment, according to the account his cellmates would later relay. Something meant as a joke, or an attempt to defuse tension. But the remark struck directly at the most vulnerable insecurity the officer carried.

The mood in the room fractured instantly.

And then the violence began.

According to what Griffith later confided to Rivers and Wame before his death, the officer attacked him with a baton, striking him repeatedly in a rage fueled by humiliation and fear. She then threatened him — warning that if he told anyone what had occurred, she would accuse him of assaulting her. Prison culture being what it is, her word would outweigh his.

Griffith returned to his cell battered, shaken, and terrified into silence. His cellmates urged him to seek help — to file a report. He refused. He believed her threat. And in prison, retaliation does not come with a paper trail.

That night, no one slept.

The Last Morning Griffith Would Ever See

The next morning brought business as usual. Breakfast. Work assignments. A sea of orange uniforms moving in synchronized monotony. But to those who knew him best, Griffith looked different. Haunted. Withdrawn. Afraid of the officer whose voice now carried the power not only to discipline him — but to destroy him.

He worked his shift in the prison shop until late morning. Then he raised his hand and asked for permission to use the restroom.

He never came back.

Minutes passed. Then twenty. Then thirty.

Rivers and Wame exchanged glances. Something was wrong.

When they persuaded a guard to let them search, they didn’t find Griffith in the restroom. They didn’t find him in the corridors. What they eventually found — or rather, overheard — would place them in mortal danger.

The Secret Meeting No One Was Meant to Hear

Down a dim hallway, behind a door left slightly ajar, the two inmates heard voices. One was Officer Devo — panicked, distraught. Another belonged to Officer Leonard Price, a senior guard with more than a decade inside the system. A third was a younger officer still new to the job.

The conversation chilled them.

Devo admitted — in frantic detail — that Griffith was dead.

She described a confrontation. An altercation. A strangulation she called “self-defense.”

And Officer Price did not react with shock.

He reacted with strategy.

Instead of calling administrators or emergency responders, Price allegedly began planning a cover-up. The body, he reportedly said, needed to be moved. The death would be explained away as a fight between inmates. The narrative would be rewritten. And an inmate’s life would become just another statistic.

When Rivers and Wame accidentally made a noise in the hallway, their fate shifted too.

They had just become witnesses.

“If You Speak, You Die.”

The two inmates were dragged inside. They saw their cellmate’s body. They saw the marks on his neck. They saw the fear in the youngest guard’s eyes — and the lethal calculation in Officer Price’s.

According to the account later pieced together, the message was simple:

Say nothing — or be killed yourselves.

They were reminded that they were inmates. Criminals. Men whose lives held little institutional value. Guards, on the other hand, were trusted. Believed. Protected.

If the prisoners talked, Price allegedly warned, they would not survive long enough to testify.

Back in their cell that night, Rivers and Wame stared at the empty bunk across from them. A space that had belonged to their friend only hours earlier now stood as a silent accusation — and a reminder that truth inside prison walls often dies before it can leave them.

They lay awake until morning, listening to the performance unfold — the shouted discovery of a body, the orchestrated chaos, the scripted lines.

When investigators finally questioned them, they said what they had been instructed to say.

They said they knew nothing.

And officially — that is still the truth.

But the real story, they would later confide privately, is far darker.

And it began not with a murder.

But with a secret.

And a laugh.

PART 3 — The Investigation That Never Was, and the Two Men Forced to Carry the Truth

In a just world, the death of an inmate in state custody would trigger a chain of independent scrutiny: outside investigators, forensic specialists, transparent record-keeping, and a process rigorous enough to uncover whatever the prison hoped to keep hidden.

But the world inside correctional walls rarely resembles the one described in policy manuals.

And in the weeks after Lamont Griffith died, the difference between theory and practice became painfully clear.

A System Designed to Clear Itself

The internal review began — at least on paper. Officials logged timelines, pulled shift rosters, and asked staff to submit written statements. But from the outset, experts say, the process was pointed in one direction:

Away from the officers.

The version recorded in official documents read like a script routinely used after inmate-on-inmate assaults: a “dispute,” a “physical altercation,” a “tragic outcome.” Names of supposed aggressors — unnamed, unverified, and ultimately uncharged — were hinted at. The case, the reports implied, was unfortunate.

But not suspicious.

Not criminal.

Not systemic.

And nowhere did the official ledger reflect the most critical fact of all:

That officers had been the last people to see Griffith alive.

Medical Evidence — Interpreted to Fit the Narrative

Medical findings recorded bruising and strangulation marks on Griffith’s neck. Under different circumstances, those findings might have prompted deeper inquiry: who had contact with him, when, and under what authority?

Instead, the report treated the injuries as though they validated the very narrative that protected the prison:

fighting inmates

heat-of-the-moment rage

no officer involvement

A death inside a violent facility, the logic went, must have been caused by violence from another inmate.

That assumption became conclusion.

Conclusion became closure.

Case closed.

The Problem With “Internal Affairs” Behind Bars

Reform advocates argue that internal corrections investigations often operate inside an echo chamber. Staff investigate staff. Supervisors review the work of the same subordinates they are responsible for supporting. Institutional loyalty exerts pressure — sometimes spoken, often implied.

The question subtly shifts from:

“What happened?”

to

“How do we contain the damage?”

If a facility is under-staffed, under-trained, or under-funded, a homicide by a staff member is not simply a tragedy.

It’s a career-ending scandal.

A lawsuit.

A political headache.

And for some institutions, truth is far too expensive.

The Ones Who Know the Truth Cannot Speak It

Inside Cell 123, the silence now had weight.

Jamal Rivers and Obiora “O” Wame were not saints. The state had labeled them felons, and society had largely stopped listening when their names were read aloud at sentencing.

But neither man had ever expected to wake up one morning and find himself a witness to murder — then be forced to remain silent under threat of becoming the next casualty.

Their dilemma was simple and devastating:

If they spoke, they would die.

Not metaphorically. Not eventually.

Literally.

The senior officer had made that fact abundantly clear.

In a system where inmate “accidents” are frequent and documentation is controlled internally, their deaths would barely merit a paragraph in the daily log.

So, they stayed silent.

And every day, the lie tightened around their throats.

The Psychological Gravity of Forced Silence

Psychologists who study confinement describe a condition often seen among prisoners who witness violence they are powerless to report: compounded institutional trauma.

It is grief multiplied by fear.

Guilt layered over survival instinct.

Rivers felt it most at night — when the noise of the day finally faded, and he was left alone with a memory he could neither erase nor share.

He pictured Griffith laughing days before the incident, joking about what he would do when he got out. He remembered the envy they felt when they thought their friend had found a connection with a woman guarding the unit. He remembered warning him:

Be careful. This is dangerous.

Then came the body.

And now came the question that never left his mind:

Was silence a betrayal… or the only way to get back to his children alive?

Wame, older and hardened by years inside, processed it differently. He had seen beatings. He had seen corruption. But he had never seen the system kill a man and rewrite the truth in real time.

Witnessing wrong is one thing.

Being coerced into legitimizing it — that is another burden entirely.

He began keeping mental distance from everyone around him — even from Rivers. Attachment, he told himself, was liability. And liability gets people killed.

The Officer Walks the Tier

Meanwhile, Officer Rochelle “Relle” Devo continued to work her shifts.

Her uniform remained immaculate. Her hair neatly pulled back. Her demeanor — cool, professional, unreadable — sent the same message every day:

Nothing to see here.

To inmates who suspected what had really happened, her presence was a cruel reminder that inside this institution, power does not simply protect — it erases.

She controlled when they slept.

When they ate.

When their cell doors slid open.

And when they slammed shut.

Most chillingly — she controlled the environment in which two critical witnesses lived out their days, acutely aware that a single wrong word, glance, or question could cost them their lives.

How Investigations Fail When Witnesses Are Afraid

On paper, investigators invite inmates to share “any information relevant to the incident.” In reality, any inmate who implicates an officer exposes himself to retaliation — not only from the officer involved but from others who close ranks.

The price for telling the truth is isolation at best.

Death at worst.

So, inmates say what they must say to survive:

“I didn’t see anything.”

“I don’t know anything.”

“He seemed fine before that.”

And the state — through willful blindness — accepts the lie.

Because the lie is operationally convenient.

It requires no external review. No trial. No scandal. No acknowledgment that the people entrusted with custody and care of inmates might have abused that power in the most irreversible way possible.

A Family Mourns Without Answers

Outside the prison walls, Griffith’s family buried him.

They received the state’s official explanation — violence among inmates — and tried to reconcile it with the man they knew. A son. A brother. Flawed. Human. Still theirs.

There were no mentions of misconduct.

No avenues to challenge the conclusion.

No transparency beyond templated administrative language.

The state — which had assumed total custody over Griffith’s life — now controlled access to the truth about his death too.

The Pattern Extends Far Beyond One Prison

Criminal justice scholars recognize this story — not in detail, but in structure. Across the country, death inside correctional facilities often disappears into reports written by the people who run them.

Independent oversight remains rare.

Fear of retaliation prevents inmates from speaking.

Conflicts of interest go unchallenged.

And data — when reported at all — tends to be stripped of context:

“Deceased inmate.”

“Undetermined inmate altercation.”

“Pending internal review.”

But behind the clinical language are human beings:

A dead man.

A grieving family.

Two witnesses trapped in fear.

And officers who learned — correctly — that the system would protect them from the consequences of their actions.

Life Moves Forward — But the Truth Does Not

Weeks blurred into months.

Then into years.

Rivers and Wame did what inmates do to survive: they worked, they slept, they avoided conflict whenever possible, and they did not speak of the day that rewrote their lives.

Their silence became muscle memory.

It became reflex.

It became prison law.

But silence does not erase memory.

It does not remove the image of their friend lying lifeless on a concrete floor — nor the sound of his killer’s supervisor calmly planning to bury the truth alongside the body.

And as release dates crept closer, a new question began to form:

What happens to the truth when the only people who carry it finally step back into the world?

Would they say nothing — forever?

Would they finally speak?

And if they did:

Would anyone listen?

PART 4 — Freedom, Conscience, and the Question the System Never Answered

Years pass differently inside prison.

Days blur. Seasons disappear. Holidays become markers of time served rather than occasions for celebration. But eventually, for those fortunate enough to reach the end of their sentence, a gate opens.

And a man walks out.

For Jamal Rivers and Obiora “O” Wame, that moment brought not only freedom — but the return of something prison had suppressed:

choice.

Choice about work.

Choice about home.

Choice about whether to finally speak the truth.

But freedom does not erase fear. It only changes its shape.

Life After Release — With a Secret No One Knows

Rivers went home to his children.

He found work through a friend. He attended church again. He sat in living rooms where soft furniture replaced steel bunks and the sound of keys did not signal control. To the outside world, he was another formerly incarcerated man trying to rebuild.

But at night, the past returned.

He would wake from sleep with the same image in his mind:

His best friend lying lifeless on the floor.

The impression of fingers around his neck.

The calm voice of a senior officer explaining how to rewrite reality.

He could not tell his mother.

He could not tell his pastor.

He could not tell his children.

Their relief at his return was too fragile to risk with a story that might pull him back into danger — or worse, be dismissed as the unreliable words of a former inmate.

So he carried it alone.

Silence, he learned, does not end at the gate.

It follows.

Wame — older, quieter, more reserved — adjusted to civilian life with the detachment of a man who had already mourned his past self. He took shifts at a warehouse. He paid his rent in cash. He avoided attention.

But the same question lived inside him:

Am I complicit — or simply alive?

It is the kind of question that does not resolve.

It lingers.

Why They Stayed Quiet — Even Outside

Advocates sometimes ask why former inmates do not speak publicly when they witness crimes inside prison. The answer, according to experts, is layered:

• Fear does not switch off.

When a man who threatened your life still works behind the same badge — or his colleagues do — silence feels like survival.

• Credibility is structurally denied.

A parolee or ex-felon alleging officer homicide faces immediate skepticism, legal risk, and reputational danger.

• Retaliation can reach beyond prison walls.

Sometimes indirectly. Sometimes through influence. Sometimes through intimidation.

And most painfully:

• There is a belief — often justified — that no one will listen.

The public rarely sees prison as a place deserving of truth.

Which is how truth dies.

Quietly.

Without witnesses.

A Death Without Accountability

To this day, no criminal charges were filed against the officers involved in Griffith’s death. The record remains what the institution originally declared it to be:

An inmate-on-inmate altercation.

A tragic incident.

Closed.

There is no mention of the storage room.

No mention of the beating.

No mention of the threat.

No mention of the two witnesses who heard a confession — and a cover-up — unfold in real time.

Griffith’s family grieves, unaware of what really happened.

His name sits on a list of inmate deaths.

And in a file drawer somewhere, a report still repeats the lie.

What This Case Reveals About the System

This story is not only about one man’s death.

It is about a system built around four dangerous truths:

Power without oversight becomes immunity.

When the same institution accused of wrongdoing controls the investigation, accountability collapses.

Fear keeps witnesses silent.

Inmates understand better than anyone that retaliation may never be proven — only experienced.

Society often sees prisoners as disposable.

Which means their deaths are easier to accept. Easier to ignore. Easier to bury under paperwork.

Truth is fragile inside closed institutions.

And once lost, nearly impossible to restore.

Without independent, external correctional oversight — with subpoena power, transparency, and protection for inmate witnesses — cases like Griffith’s are not anomalies.

They are inevitabilities.

The Human Cost of Silence

Rivers once described the weight of the secret like this:

“It feels like carrying a man on your back who never lies down.”

He lives with it still.

So does Wame.

Their silence kept them alive.

It also sentenced them to memory.

And memory does not parole.

The Question That Still Has No Answer

The state’s duty to inmates is simple — at least in law.

Once a person is in custody, the government assumes responsibility for their safety. Their punishment is the sentence imposed by the court — not abuse, not humiliation, and certainly not unlawful death.

But when those entrusted to enforce the rules become the ones who break them — and the institution looks away — another question emerges:

Who protects inmates when the protectors are the threat?

For Griffith, that question came too late.

For Rivers and Wame, it remains the quiet burden they will carry for the rest of their lives — a reminder that sometimes the most dangerous place to tell the truth is inside the walls built to hold it.

And as long as those walls remain opaque, there will always be more stories like this one — whispered, feared, and almost never believed.

Because inside America’s prisons, silence is not just culture.

It is policy.

News

Ethan finally felt chosen—until a Sunday dinner flipped everything. His new wife went pale when his brother walked in… because she used to be married to him, before she transitioned. “It wasn’t the revelation that turned deadly, but Ethan’s fear of always being “second,” and pride did the rest.” | HO

The 29-year-old husband discovered that his new wife was his brother’s transgender ex-wife, so he… When someone builds a new…

She Was Live-Streaming Her Fight with Her Mother-in-Law — Minutes Later, Her Husband 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐭 Her | HO

She Was Live-Streaming Her Fight with Her Mother-in-Law — Minutes Later, Her Husband 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐭 Her | HO Margaret Elaine Cole,…

Married 24 years, they came on a game show for laughs—until she hesitated at one question: “Would you still marry him?” He walked offstage. Everyone thought it was the end. Twist: he came back, got on one knee, and handed her a medical school application—“No more choosing love over your dream.” | HO!!!!

Married 24 years, they came on a game show for laughs—until she hesitated at one question: “Would you still marry…

He bragged online about his “upgrade” and the diamond ring, convinced he’d outgrown his quiet ex. While he planned the wedding, she quietly stepped into a billionaire inheritance—and bought the company behind his venue. AND his reception got shut down mid-toast… by his ex’s “welcome to new ownership” call. | HO!!!!

He bragged online about his “upgrade” and the diamond ring, convinced he’d outgrown his quiet ex. While he planned the…

He Walked In On his Fiancee 𝐇𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐒*𝐱 With Her Bestie 24 HRS to Their Wedding-He Gets 𝐒𝐡𝐨𝐭 𝟏𝟑 𝐓𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐬 | HO!!!!

He came home early—24 hours before the wedding—and found his fiancée in bed with her “best friend.” He didn’t yell….

Steve Harvey STOPS the Show — Husband’s MISTRESS Was in the Audience the Whole Time | HO!!!!

Family Feud looked normal—until Steve noticed one woman in a red dress staring a little too hard at the stage….

End of content

No more pages to load