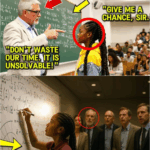

Harvard Professor Called It IMPOSSIBLE—Then a 12-Year-Old Girl Raised Her Hand and Shocked the World!

In the grand, wood-paneled lecture hall of Harvard, the air was thick with expectation. Professor Richard Harrington, the university’s most celebrated mathematician, stood at the podium, his voice ringing with authority. “You’re wasting everyone’s time with these unfounded theories,” he snapped, eyes fixed on a small figure in the second row.

That figure was Amara Johnson—just 12 years old, from Dorchester, Boston. The room, filled with prodigies from elite schools, expected her to shrink under the weight of Harrington’s dismissal. But Amara quietly raised her hand. “I’d like to present my solution to the Hamilton Watanabe conjecture,” she said, her voice steady.

No one could have predicted what happened next.

A Mind Unseen

From a cramped apartment in a struggling neighborhood, Amara’s world was numbers. Her father, Marcus, a bus driver, worked double shifts to keep their lives afloat after Amara’s mother passed away. Every spare dollar went toward secondhand math books, which Amara devoured with a hunger most kids reserved for candy.

Her teachers didn’t know what to make of her. Most ignored her, but Ms. Williams, the only Black teacher at Roosevelt Middle School, saw the spark. She slipped Amara a battered college textbook, whispering, “The world won’t always make space for brilliant Black girls. You’ll have to claim it.”

A Doorway to Harvard

When Harvard announced a special program for gifted students, Ms. Williams fought to get Amara in, facing down a principal who scoffed, “Be realistic. This is for kids from Boston Latin, not Dorchester.” But Amara’s application—filled with original solutions and creative proofs—couldn’t be denied.

The acceptance letter arrived. Amara’s father lifted her off the ground in a bear hug. “Of course you got in! They’d be fools not to take my brilliant girl.”

Yet, as she stepped onto Harvard’s campus in her secondhand blazer, Amara felt the weight of a world that didn’t expect her to belong.

The Impossible Problem

On her first day, Professor Harrington introduced the Hamilton Watanabe conjecture: an unsolved problem that had stumped the world’s greatest mathematicians for decades. “Even I,” he boasted, “have made only modest progress. It is, for all practical purposes, impossible.”

Amara’s hand shot up. “Couldn’t we approach this by examining divergence patterns rather than convergence?” she ventured.

Harrington’s lips curled. “Perhaps save your questions until you’ve mastered undergraduate mathematics,” he replied, as laughter rippled through the room.

But Amara’s mind was already racing. That night, she covered her bedroom wall with equations, searching for a pattern no one else could see.

The Breakthrough

Three weeks in, Amara’s approach—unconventional, creative, and rigorous—began to take shape. She found an unlikely ally in Samuel, a quiet boy from Boston Latin. Together, they explored her radical ideas, even as Harrington dismissed them as “mathematical fantasy.”

“Don’t let someone else’s limitations become yours,” her father reminded her. And Amara refused to quit.

A chance encounter changed everything. Dr. Elaine Carter, a pioneering Black mathematician at Harvard, noticed Amara’s work. “Your intuition is extraordinary,” Dr. Carter said. “Let’s develop this together.”

Under Dr. Carter’s mentorship, Amara’s ideas crystallized into a coherent, elegant proof. The impossible problem was yielding—not to tradition, but to fresh eyes.

The Showdown

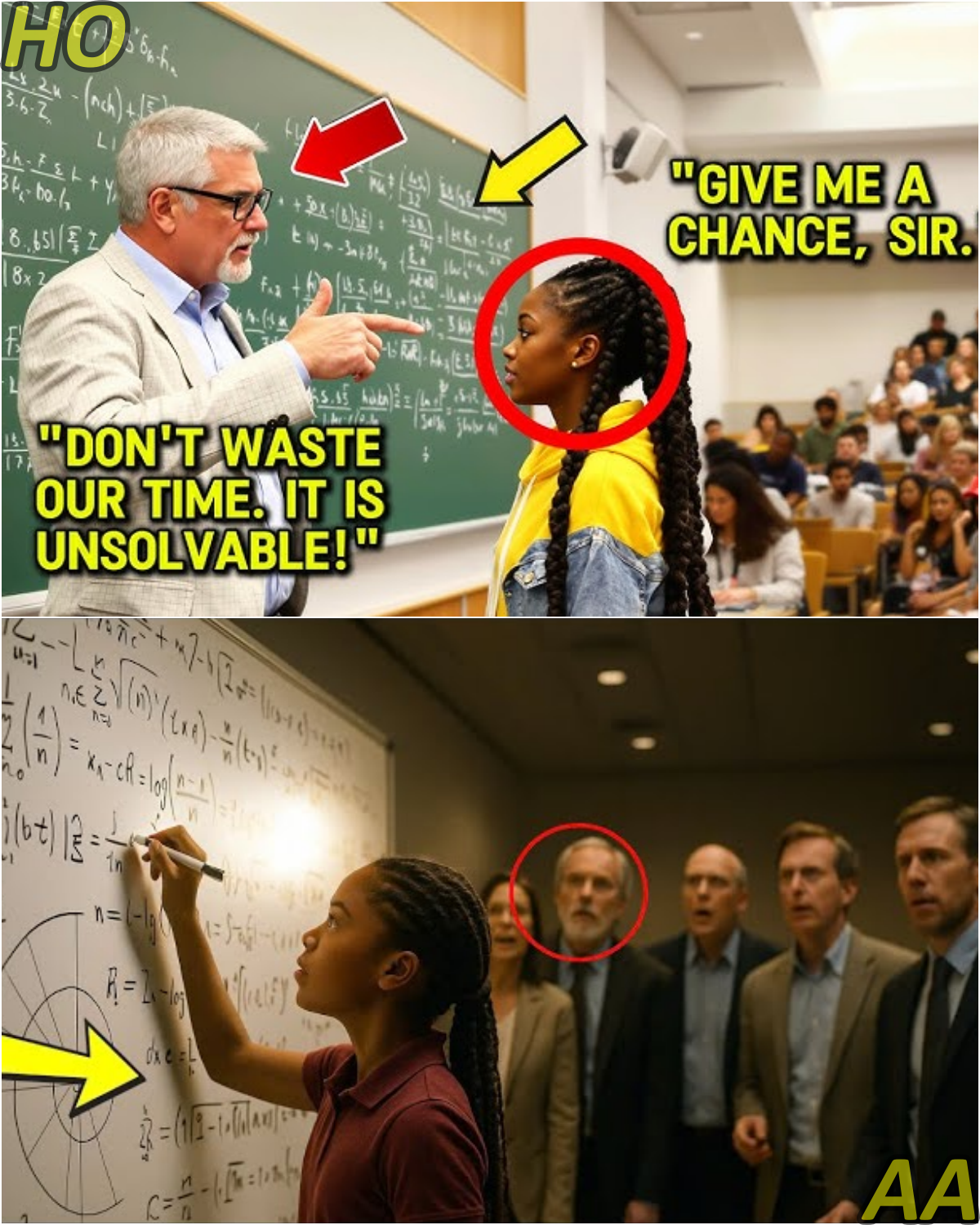

Presentation day. The auditorium was packed with professors, grad students, and skeptical prodigies. Harrington, certain of his own authority, dismissed Amara’s request to present. But Dr. Carter intervened. “Academic inquiry demands we consider all serious approaches.”

Amara took the podium. Her voice was clear and confident as she walked through her solution, redefining the relationship between prime numbers and quantum states, reframing the problem in a new mathematical dimension.

At first, silence. Then, a wave of murmurs—then applause. Mathematicians peppered her with questions. Amara answered each with poise and precision.

Harrington tried to dismiss her work as “creative, but not proof.” But the faculty challenged him. “Let her defend it,” a senior professor called. Amara did—and her solution held.

Vindication

Within days, a Harvard review committee validated Amara’s proof. The news exploded: “12-Year-Old Girl Solves Impossible Harvard Problem!” Math journals, newspapers, and TV crews all wanted her story.

Harvard offered Amara a special program, and the mathematics department established the Johnson Scholarship for underrepresented students. Even Harrington, humbled, stepped down from his post, admitting, “Your approach revealed my own blind spots. That’s a lesson for any mathematician.”

Victoria, the class’s former queen bee, sought Amara out. “I was wrong about you,” she admitted. “Mathematics doesn’t care about our assumptions. It only cares about truth.”

A New Beginning

A year later, Amara stood on stage at the Boston Science Center, now 13, inspiring a new generation of students from neighborhoods like hers. “The greatest barrier wasn’t the mathematics,” she said. “It was convincing others I deserved to be in the room.”

She smiled at her father, Ms. Williams, Dr. Carter, and Samuel—all who had believed in her.

“Impossible is just a word people use when they’ve stopped looking for solutions,” Amara told the crowd. “The best mathematicians are the ones who never stop questioning.”

News

Teacher Told Black Student to Solve Higher Grade Math Problem as a Joke—What Happened Next Changed Everything – s

Teacher Told Black Student to Solve Higher Grade Math Problem as a Joke—What Happened Next Changed Everything The classroom fell…

A 13-Year-Old Black Boy Vanished in 1989 — 6 Years Later, He Was Found Behind a Fake Wall – S

A 13-Year-Old Black Boy Vanished in 1989 — 6 Years Later, He Was Found Behind a Fake Wall In the…

🚨 BREAKING: 50 Cent Vows to BLOCK Diddy’s Pardon—Music Industry in PANIC Mode to Keep Diddy Silent! This Is Getting SCARY – s

🚨 BREAKING: 50 Cent Vows to BLOCK Diddy’s Pardon—Music Industry in PANIC Mode to Keep Diddy Silent! This Is Getting…

🚨 BREAKING: Fat Joe Hit With Explosive Lawsuit! “Male Cassie” Emerges—RICO Allegations, S3xual Coercion, and Mafia-Style Intimidation—This Is Diddy-Level BAD! – s

🚨 BREAKING: Fat Joe Hit With Explosive Lawsuit! “Male Cassie” Emerges—RICO Allegations, S3xual Coercion, and Mafia-Style Intimidation—This Is Diddy-Level BAD!…

🚨 Cardi B’s “Outside” Explodes on the Charts—But Where’s Stefon Diggs? Fans Spiral as NFL Star Stays Silent! – S

🚨 Cardi B’s “Outside” Explodes on the Charts—But Where’s Stefon Diggs? Fans Spiral as NFL Star Stays Silent! The queen…

💅 Cardi B Just Made It Official With Stefon Diggs – And Her Manicure Says It All! – S

💅 Cardi B Just Made It Official With Stefon Diggs – And Her Manicure Says It All! Y’all, Cardi B is never…

End of content

No more pages to load